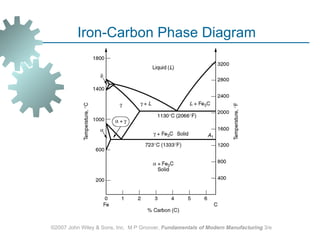

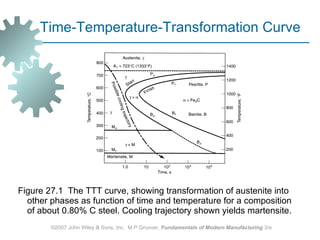

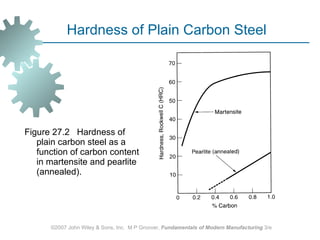

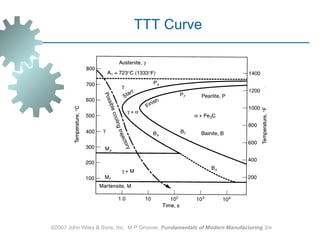

The document discusses various heat treatment methods used in manufacturing to alter the mechanical properties of metals. It describes common heat treatments like annealing, hardening, and surface hardening. Annealing is used to soften metals by heating and slow cooling. Hardening involves rapidly cooling from high temperatures to form hard martensite. Surface hardening methods like carburizing add carbon to the surface. Heat treatments require specialized furnaces, and some methods selectively heat only surface areas.