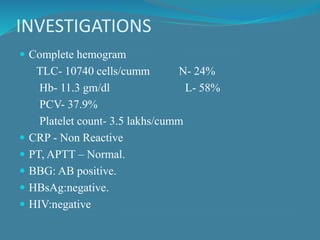

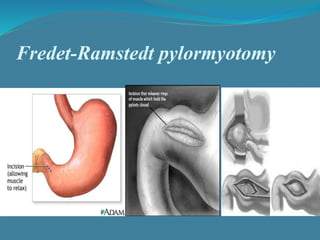

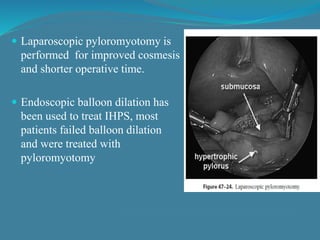

This document summarizes the case of a 1 month 18 day old male infant presenting with projectile vomiting for 7 days and abdominal distension for 3 days. On examination, the infant has a visible lump in the epigastrium. Based on examination findings and ultrasound results showing an elongated hypertrophic pylorus, the infant is diagnosed with infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. He undergoes pyloromyotomy surgery and makes a good postoperative recovery.