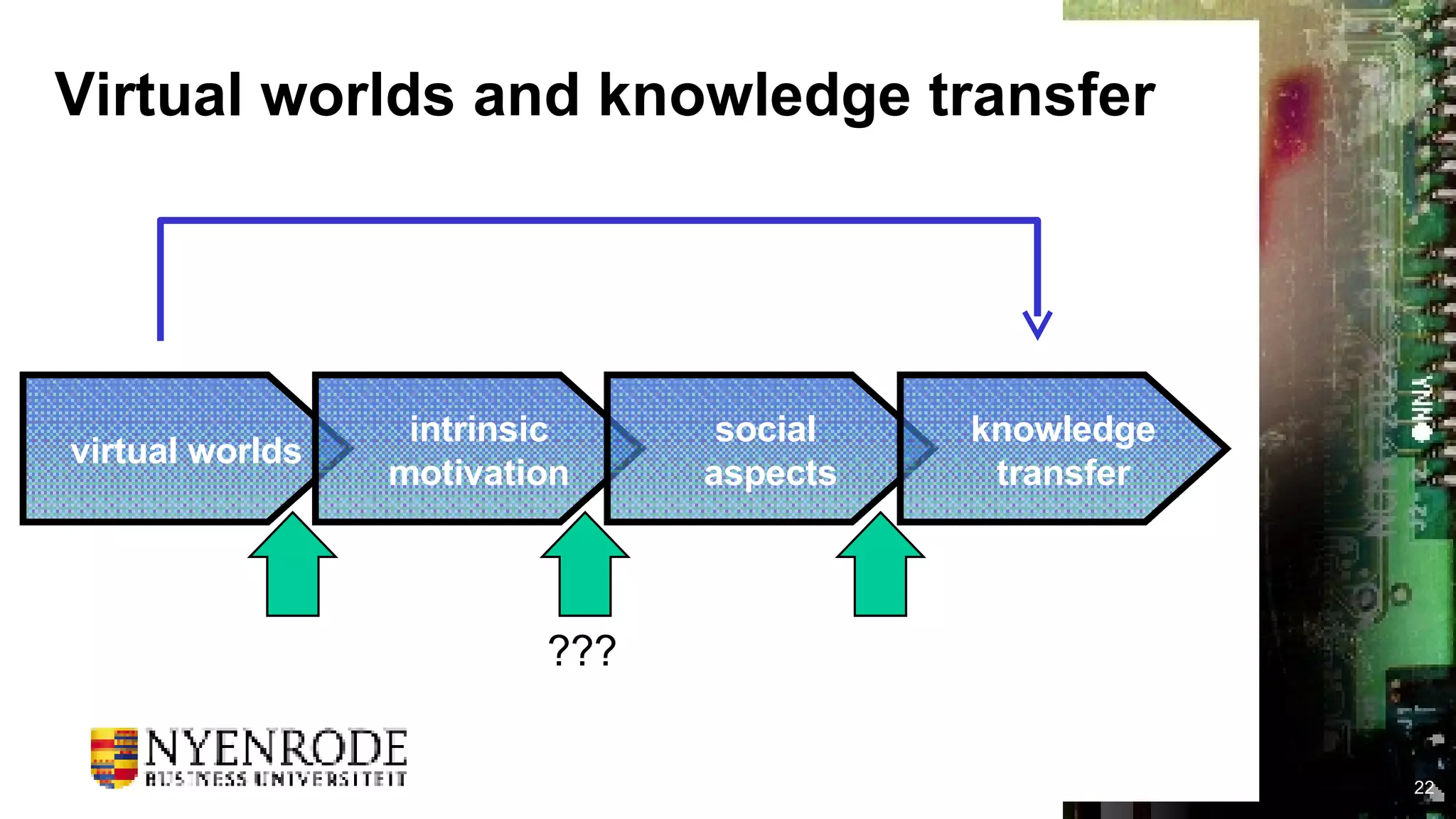

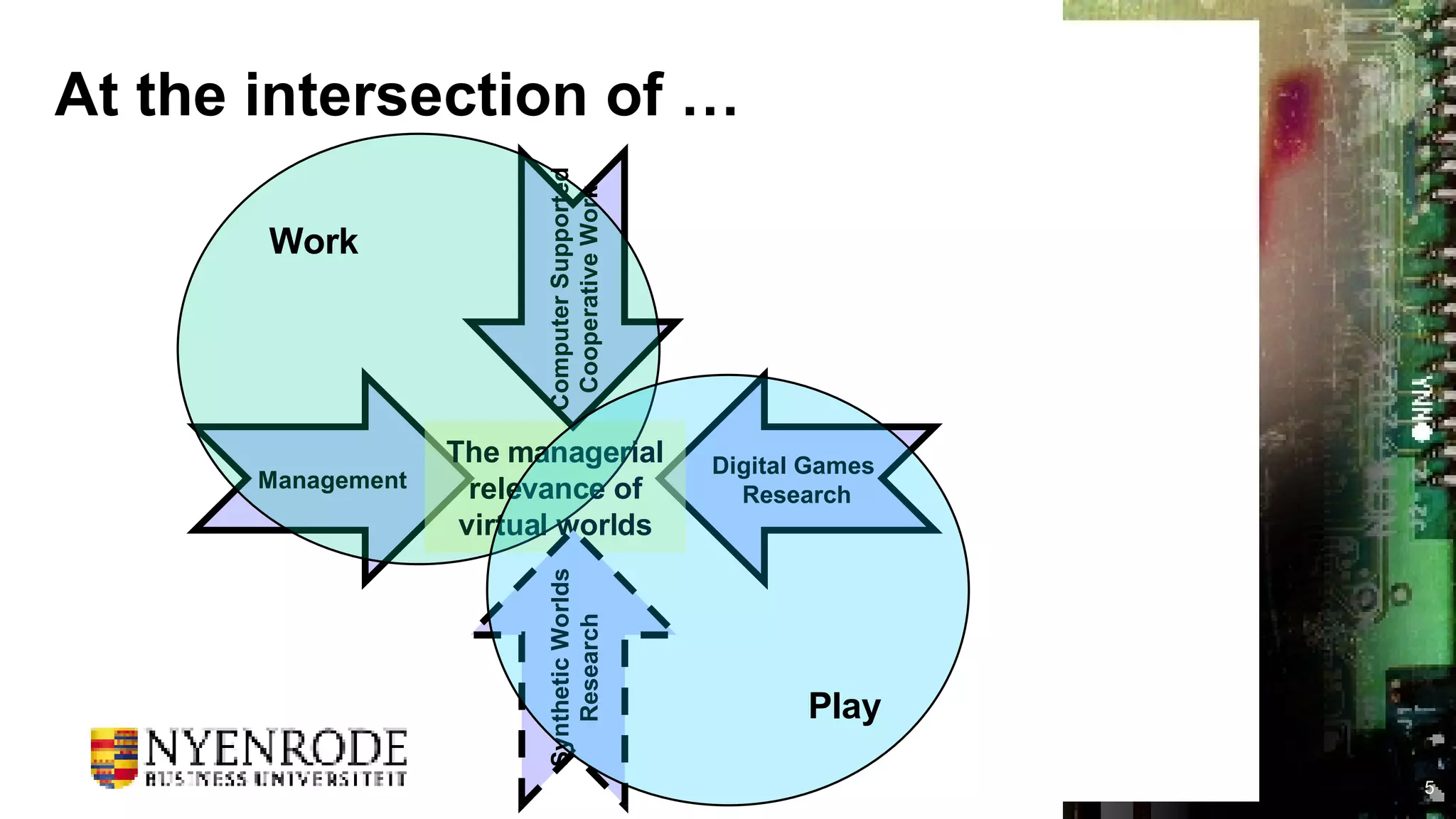

The document discusses the managerial relevance of virtual worlds for enhancing knowledge transfer within enterprises, highlighting the need to explore intrinsic motivation in virtual environments. It contrasts traditional computer-supported cooperative work (CSCW) with virtual worlds, emphasizing the potential for spontaneous and informal interactions that foster trust and creativity. The author is currently conducting research in this area, using examples from environments like World of Warcraft to investigate effective knowledge transfer practices.

![A fundamental problem of approach? “ [T]elecommunications research seems to work under the implicit assumption that there is a natural and perfect state - being there - and that our state is in some sense broken when we are not physically proximate. The goal then is to attempt to restore us, as best as possible, to the state of being there. [This orients] us towards the construction of crutch-like telecommunication tools (…)” Jim Hollan & Scott Stornetta (1992)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bridging-the-gap-communities-and-technologies-28-june-20074892/75/Bridging-The-Gap-Communities-And-Technologies-28-June-2007-9-2048.jpg)

![Illustration of extrinsic motivation “ You have to be extremely focused on results [when you work in a virtual team]. People that are focused on the process will most likely have big problems. That’s because the satisfaction you get from the process is very low.” “ The first thing you notice about virtual meetings is that they are much more businesslike, more to the point than regular meetings. Whereas in regular meetings people exchange some small talk and talk about personal things, this is lost in virtual meetings.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bridging-the-gap-communities-and-technologies-28-june-20074892/75/Bridging-The-Gap-Communities-And-Technologies-28-June-2007-13-2048.jpg)