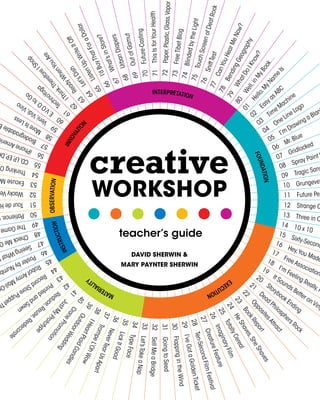

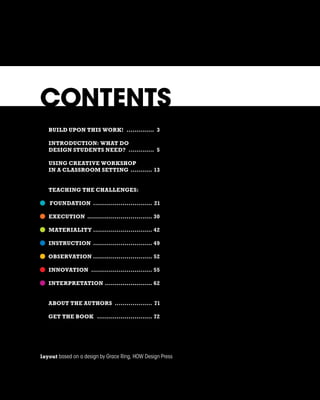

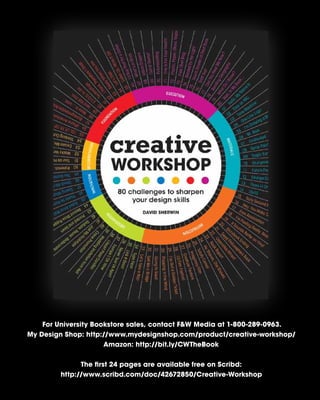

Creative Workshop aims to teach design students skills that are often overlooked in traditional design education but are critical for professional success, such as ideation, collaboration, sketching, and resilience. While job listings emphasize technical skills, creative directors seek candidates who can conceptualize ideas, execute them effectively through collaboration, and think on their feet under pressure. Short, challenging design exercises done in a classroom setting may help students acquire these skills more quickly than traditional long-term projects. The book and teacher's guide provide 80 such exercises spanning all design disciplines that can be completed in a short time period to develop these vital real-world capacities.