This document summarizes a presentation on implementing the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) liquidity framework. It discusses:

1) An overview of the NSFR and how it differs from the Liquidity Coverage Ratio in measuring long-term versus short-term liquidity;

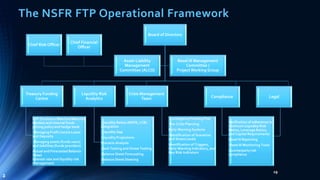

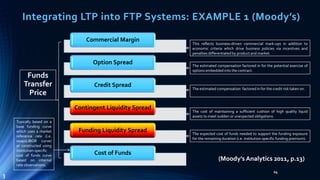

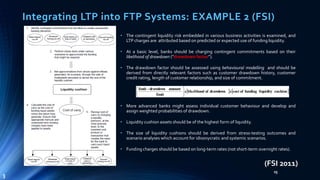

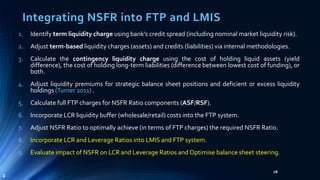

2) How to build the NSFR into funds transfer pricing (FTP) logic by updating FTP systems to incorporate long-term funding costs and risks;

3) Integrating the NSFR into existing FTP and liquidity management systems through a liquidity transfer pricing framework that allocates liquidity costs and benefits.

![Integrating LTP into FTP Systems: EXAMPLE 3 (Matz)

• DIRECT current mismatch costs :

• Mismatch (term structure) costs;

• Mismatch component of liquidity risk is fairly stable;

• Debits and credits should equal after adjustment (e.g. liquidity life of

indeterminate maturity deposits, rollover life of retail time deposits).

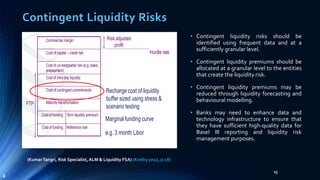

• INDIRECT future contingent costs:

• Standby liquidity costs;

• Contingency component of liquidity risk is very volatile;

• Charges and credits need to be 100% assigned to products and business

activities, and full amount of cost (but no more) is allocated as income

to contingent liquidity risk hedges.

• The cost of liquidity contingency risk is the hedge cost:

• Holding unencumbered high-quality marketable assets: Cost is the

forgone income, the opportunity cost, resulting from the choice to hold

lower-yielding assets.

• Holding stable long-term liabilities: Cost is the difference between the

actual cost of funding and the lowest possible cost.

26

Mismatch term or structural risk is

charged for consuming liquidity

risk, and the offsetting credit is

applied to existing liabilities.

Unfunded

Funded

Revolving Loan

Contingent risk is charged on

unfunded portion of loan, and

offsetting credit is split between

unpledged buffer assets hedge and

long-termliabilities hedge.

Unpledged Liquid

Assets Held

Long Term

Liabilities*

Core Deposits

Long Term Liabilities

Contingent

Charges &

Credits

Mismatch

(Structural)

Charges &

Credits

Liquidity Charges

* Only amounts required to cover contingent risk

(Matz 2011, p.464)

[Sourced from Joanne Trefrey, Bank of Monntreal]

(Matz 2011)

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ftpnsfr1stpresentationfinal-140922131313-phpapp02/85/Basel-III-NSFR-Liquidity-Framework-Theoretical-Implementation-Requirements-26-320.jpg)

![Strategic Considerations: Increasing the NSFR

“The changes may go beyond simply changing the composition

of existing balance sheets; banks may also need to exit some

businesses or adopt new business models” (King 2013, p.4153)

31

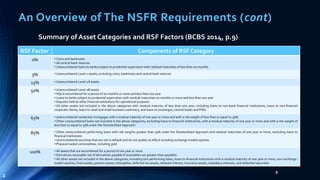

King (2013):

• The study estimated the NSFR for banks in 15 countries and the

impact on Net Interest Margins (“NIMs”).

• The analysis showed suggested that banks in France, Germany,

Switzerland, and the UK might experience greatest declines in

NIMs in meeting NSFR, owing to their universal banking model with

highly diversified funding and a high concentration of trading assets.

• Average decline for them was -156 basis points (“bp”) compared to

-27 bp for 6 other banks (Canada; Mexico; Netherlands; Spain;

Italy;Australia) below NSFR ratio.

• Banks must either increase ASF, reduce RSF, or both by: (1)

extending maturity of wholesale funding (2) Increase the share of

corporate loans to retail loans and shorten maturity; (3) sell

investments and increase cash holdings; and (4) increase holding

of high-quality liquid bonds.

[Study was based on a sample of (commercial, investment, savings, cooperative, and

mortgage) banks in 15 countries (Australia; Canada; Chile; France; Germany; Hong Kong;

Italy; Japan; Korea; Mexico; Netherlands; Spain; Switzerland; UK; USA) using income

statement and balance sheet data as of year-end 2009]

Strategies to increase the NSFR (King 2013, p.4147)

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ftpnsfr1stpresentationfinal-140922131313-phpapp02/85/Basel-III-NSFR-Liquidity-Framework-Theoretical-Implementation-Requirements-31-320.jpg)

![Strategic Perspectives

32

IMF (2014):

• High number of banks meeting minimum 100% NSFR

threshold (86% out of total of 2,079 banks) at end-

2012 (excluding France, Germany, Portugal, Slovenia).

• Sensitivity tests used showed NSFR is sensitive to

changes in the weights assigned to loans and

deposits, and less to securities and OBS categories,

i.e. changes in loan and deposit weights will have a

substantial impact on how banks meet/do not meet

100% NSFR threshold.

• Socio-economic and political context needs to be

taken into account, e.g. high NSFR ratios may reflect

a lack of confidence in the system or potential balance

of payment problems indicated by high government

securities holdings and deposits.

[Study was based on an empirical analysis of end-2012 financial data for

2,079 banks covering 128 countries]

PwC (2014):

• Secured financing transactions unduly penalised as

transacted with non-banks (50%weighting).

• Disruptive impact on derivatives (50% weighting with

central clearing house), repos, and trade finance

agreements (50%weighting).

• Three potential options for dealing with NSFR:

1. reduce volume of NSFR-unfriendly transactions (likely

to erode market credibility;

2. reduce asset-liability mismatch by reducing tenor of

assets (likely to lead to loss of clients seeking

alternative maturities elsewhere);

3. extend maturities of liabilities (most viable option).

[Findings are partly based on the views of bankers attending a PwC-hosted

round table on the latest developments in NSFR]

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ftpnsfr1stpresentationfinal-140922131313-phpapp02/85/Basel-III-NSFR-Liquidity-Framework-Theoretical-Implementation-Requirements-32-320.jpg)