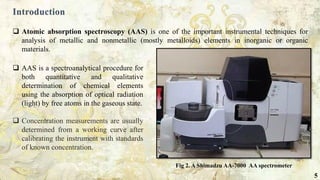

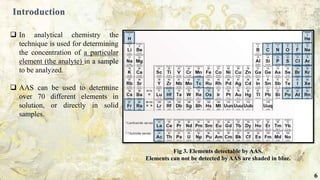

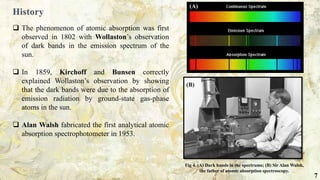

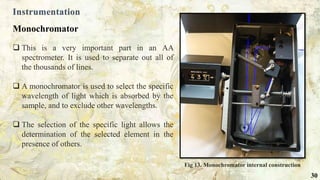

The document provides a comprehensive overview of atomic spectroscopy, particularly focusing on atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) as an analytical technique for determining elemental composition in various samples. AAS operates on the principle of measuring light absorption by free atoms in a gaseous state and requires calibration with standards of known concentration for accurate results. It discusses instrumentation, including light sources, atomizers, and detectors, as well as practical applications in fields such as environmental science and pharmaceuticals.