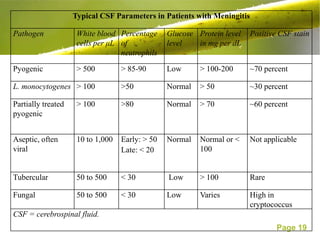

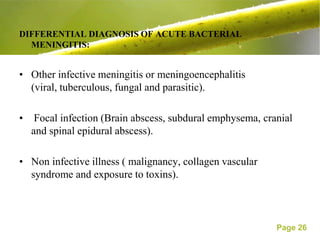

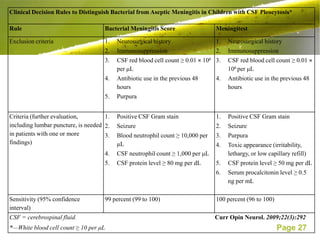

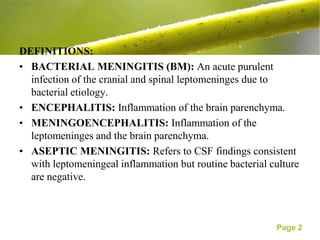

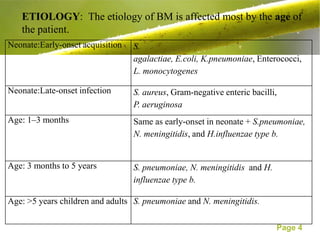

This document discusses the management of bacterial meningitis in children. It defines bacterial meningitis and related terms. The most common causes are Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae type b. Risk factors include age and immune deficiencies. Diagnosis involves lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid analysis showing pleocytosis, low glucose, and high protein. Treatment involves intravenous antibiotics and management of increased intracranial pressure. Outcomes depend on early diagnosis and treatment.

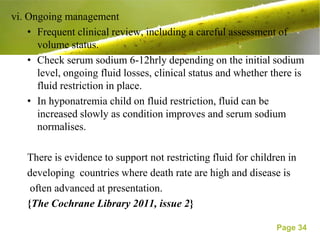

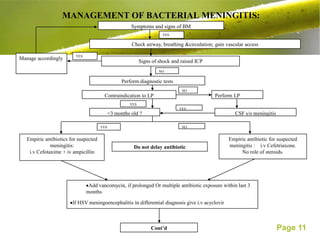

![Reduced or fluctuating conscious level or focal neurological signs

NO YES

Full volume maintenance fluid [Isotonic fluid-DNS or NS]. Perform CT scan

Do not restrict fluid unless there is SIADH or raised ICT.

Monitor fluid administration, urine output,electrolytes and blood

glucose.

Close monitoring for signs of raised ICP ,shock and repeated review.

If LP contra-indicated, perform delayed LP when no longer contra-

indicated.

Specific pathogen identified

YES NO

Antibiotics for confirmed meningitis. Antibiotics for unconfirmed

meningitis.

<3 months old?

NO

YES

i.v cefotaxime + ampicillin i.v for ≥14 days Ceftriaxone ≥ 10 days

Page 12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bacterialmeningitis-130405141226-phpapp01/85/Bacterial-meningitis-12-320.jpg)

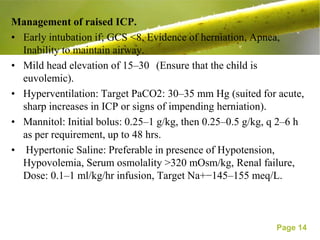

![• Adequate sedation and analgesia.

• Prevention and treatment of seizures: use Lorazepam or

midazolam followed by phenytoin as initial choice.

• Avoid noxious stimuli: use lignocaine prior to ET suctioning

[nebulized (4% lidocaine mixed in 0.9% saline) or intravenous

(1–2 mg/kg as 1% solution) given 90 sec prior to suctioning].

• Control fever: antipyretics, cooling measures.

• Maintenance IV Fluids: Only isotonic or hypertonic fluids

(Ringer lactate, 0.9% Saline, 5% D in 0.9% NS), No

Hypotonic fluids.

• Maintain blood sugar: 80–120 mg/dL.

• Refractory raised ICP - Barbiturate coma, Hypothermia and

Decompressive craniectomy.

Page 15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bacterialmeningitis-130405141226-phpapp01/85/Bacterial-meningitis-15-320.jpg)