1. The document discusses how digital technology and computers have changed calligraphy and its production and experience. It argues that computers can be useful tools for calligraphy by making the process more efficient and opening new possibilities, while still maintaining the art form.

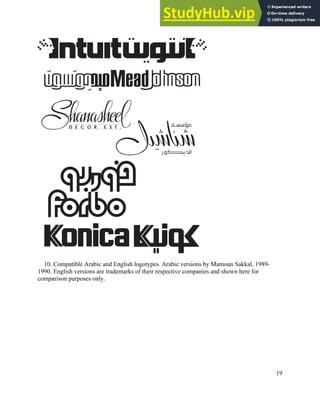

2. It provides examples of how the author has used computers in innovative ways to modify and layer calligraphy designs in digital works while still expressing creativity. Computers have also allowed application of calligraphy to architecture at a larger scale and lower cost.

3. While some fear computers may negatively impact calligraphy, the document argues the mental design is most important, and computers can replace manual production steps without affecting the art form, as traditional processes were also not always a single