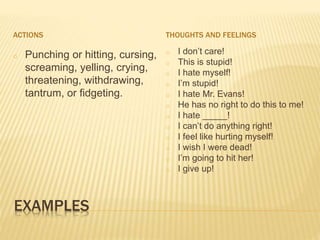

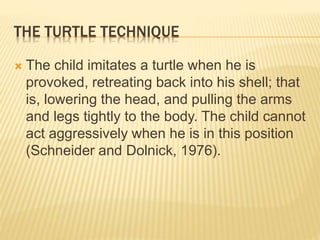

This document provides definitions and models of anger in children. It defines anger as a normal emotion triggered by frustration that can be expressed overtly, covertly, or inwardly. Models of anger-prone children include the constitutional model of temperament, the reinforcement model of attention-seeking behavior, and the social learning model of observing aggression in others. Triggers of anger include frustration, fear, shame, lack of assertiveness, and pre-existing negative states. Characteristics of anger-prone children are habitual outbursts disproportionate to events, negative thinking patterns, catastrophic thinking, and seeing anger as part of their identity.