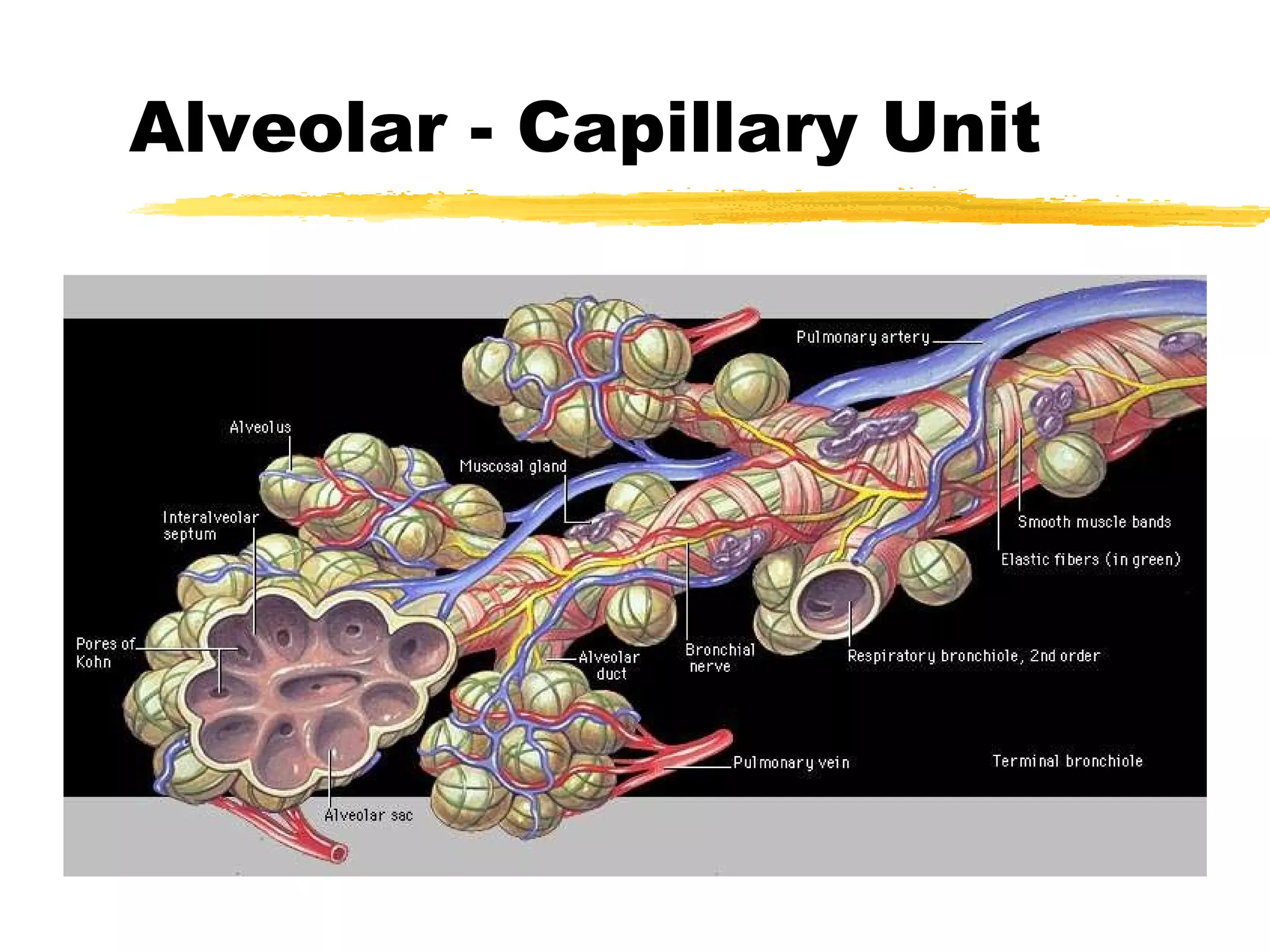

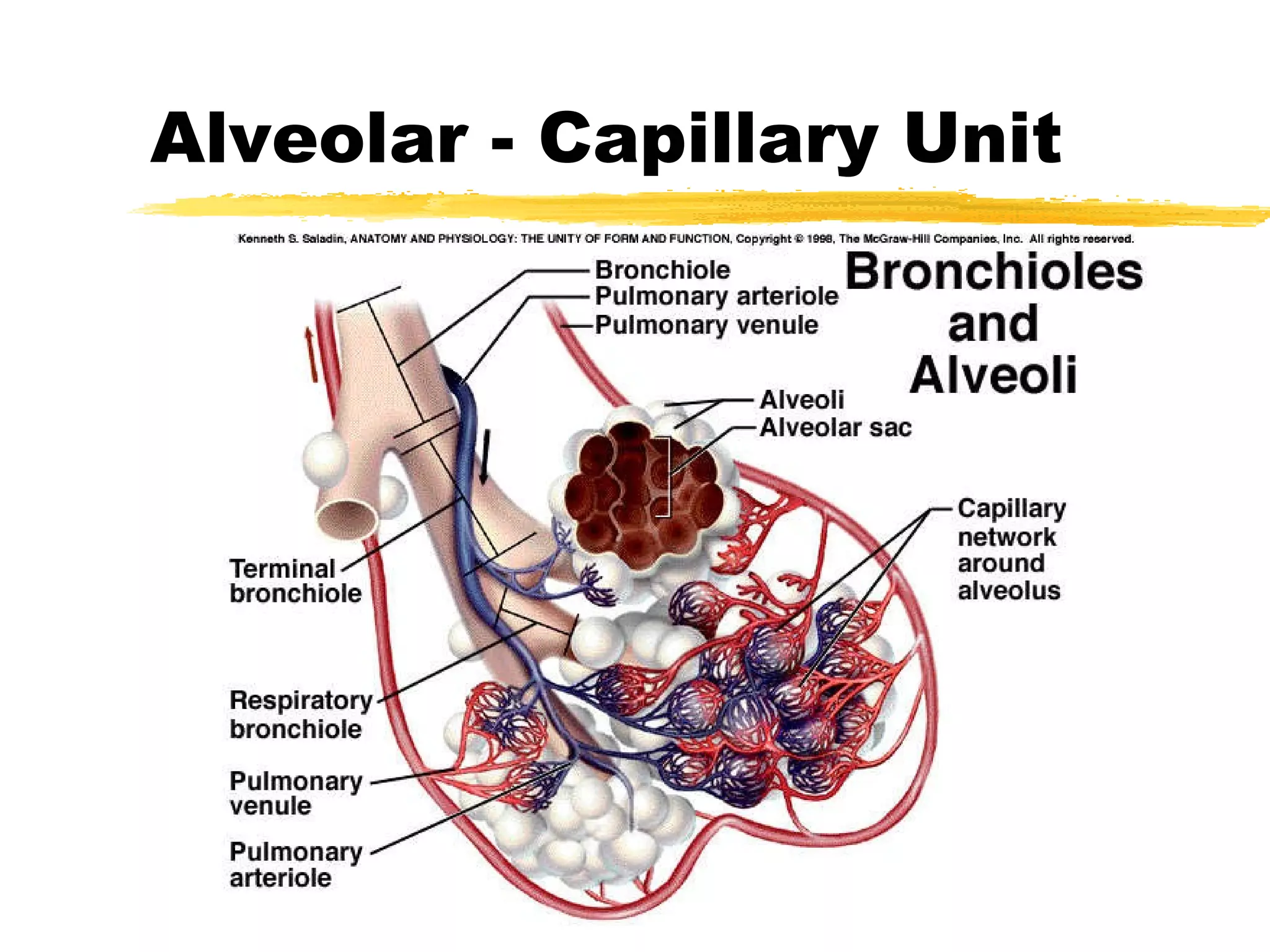

1. The alveolar-capillary unit is a complex structure that facilitates gas exchange through diffusion between alveoli and surrounding capillaries. It provides a thin barrier and large surface area for oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange.

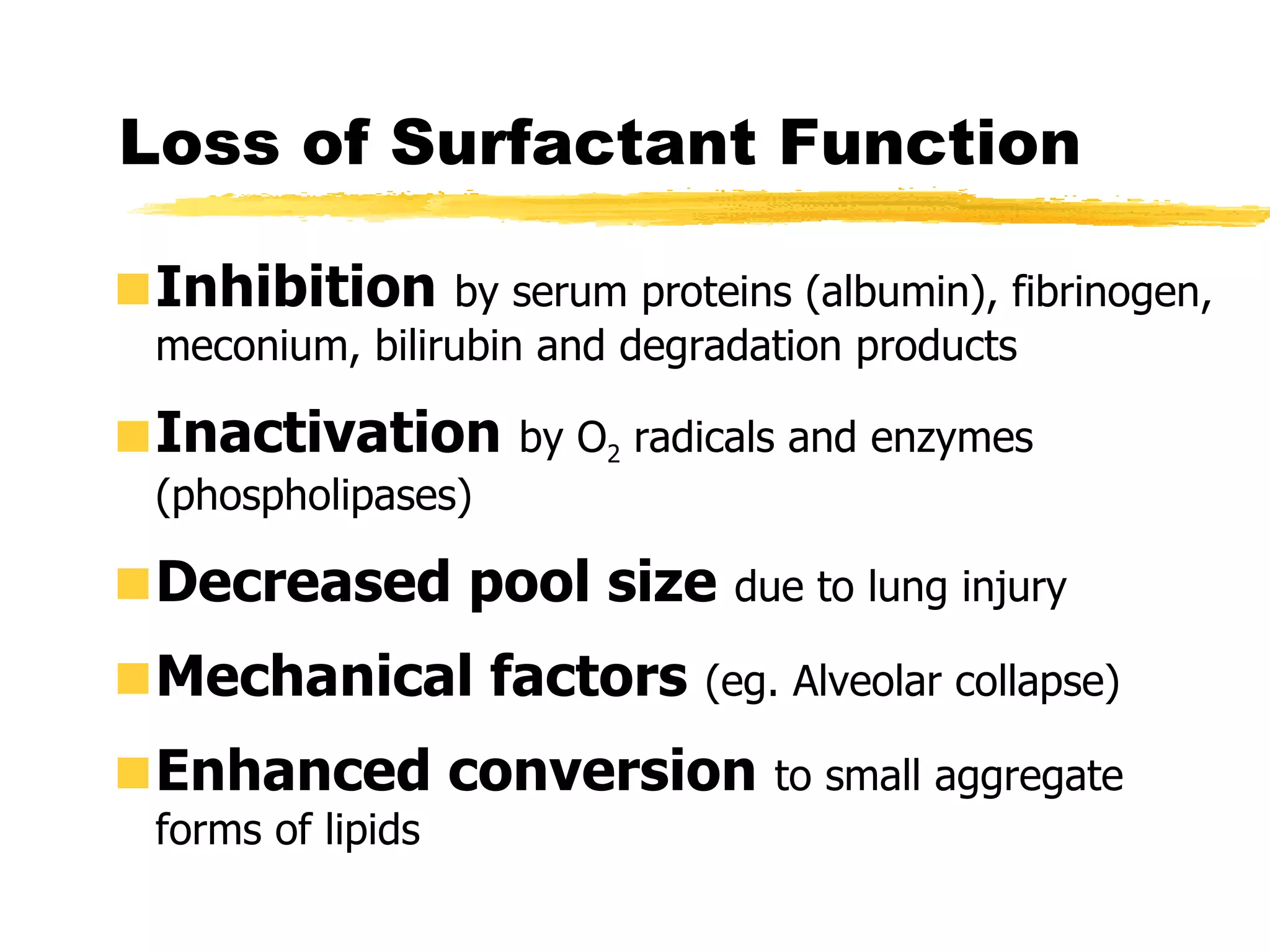

2. Surfactant, produced by type II alveolar cells, reduces surface tension in alveoli to increase lung compliance and prevent collapse during expiration. It plays several roles including reducing work of breathing and stimulating the lung's immune system.

3. Gas exchange occurs through diffusion as blood passes through alveolar capillaries. Oxygen diffuses into the blood from alveoli while carbon dioxide diffuses out of the blood into alveoli based on partial pressure gradients

![The Foetal Lung Airways formed by week 16 Alveoli start to form ~ at week 20; ~20 million alveoli present at birth Alveolar type II cells appear ~ at week 24 Foetal lung fluid (5 ml/kg/hr) maintains lung at FRC [high Cl - , low HCO 3 and protein c.f. plasma] Foetal breathing: development of neural control](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/alveolarcapillaryunit-13024032865998-phpapp01/75/Alveolar-Capillary-Unit-37-2048.jpg)