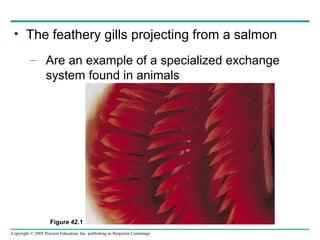

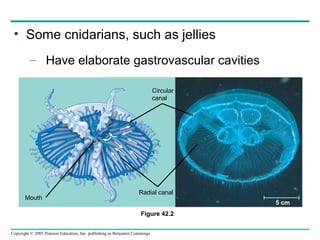

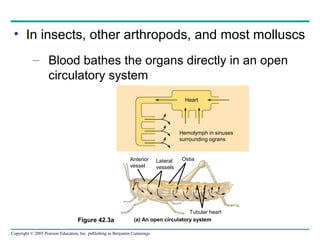

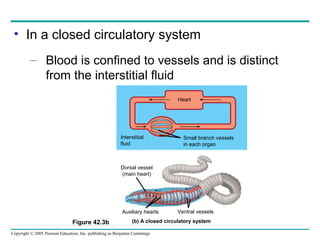

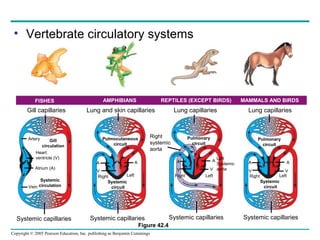

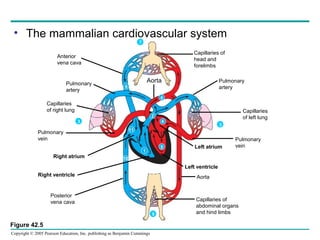

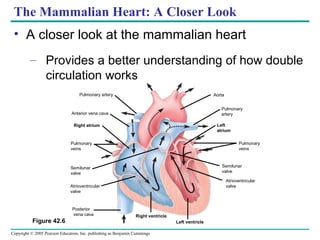

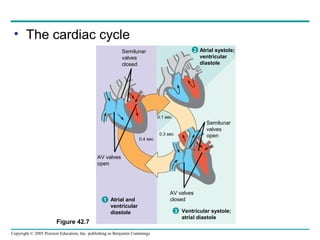

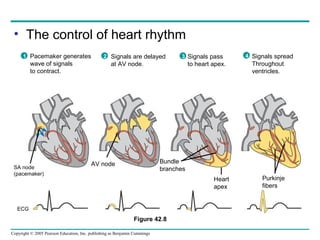

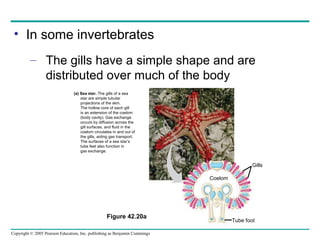

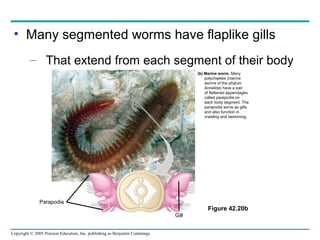

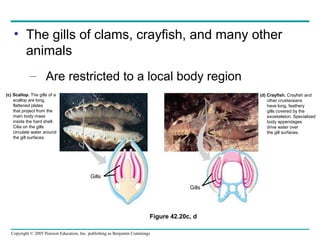

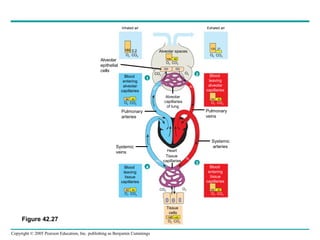

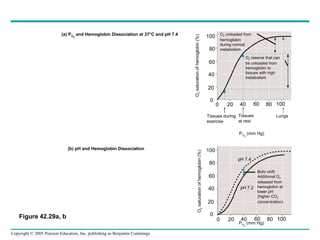

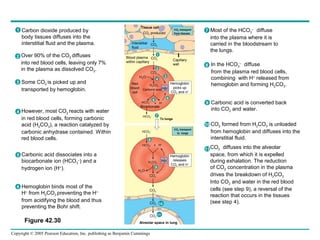

The document summarizes circulation and gas exchange in organisms. It discusses how unicellular organisms directly exchange with their environment while multicellular organisms need specialized exchange systems like circulatory systems. It describes different circulatory systems seen across invertebrates and vertebrates, from simple gastrovascular cavities to open and closed circulatory systems. The mammalian circulatory system is discussed in detail, outlining the pathway of blood flow through the heart in double circulation and how the heart's rhythmic pumping is controlled.