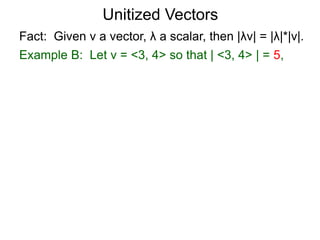

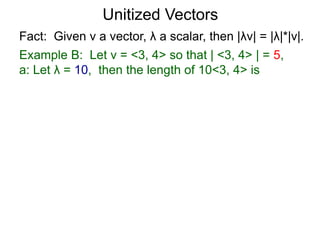

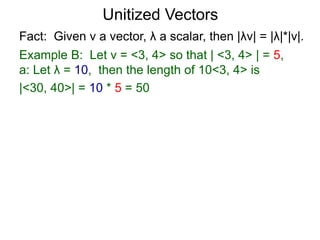

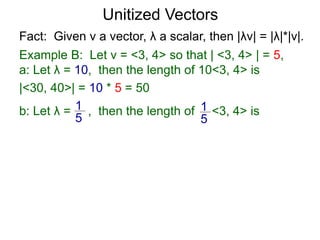

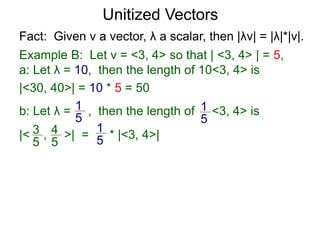

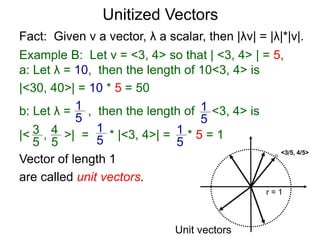

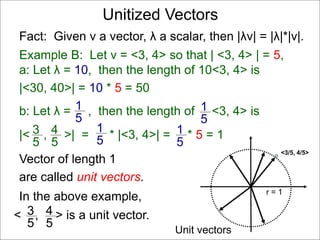

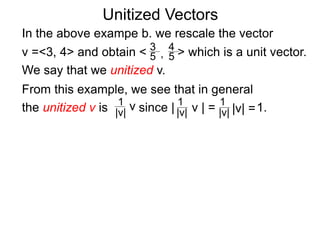

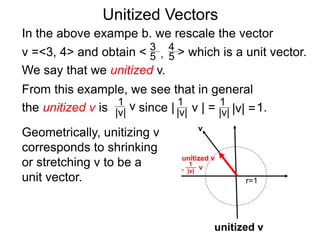

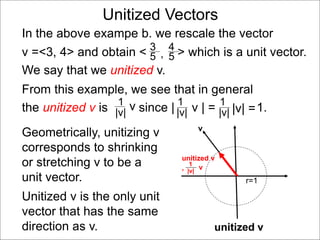

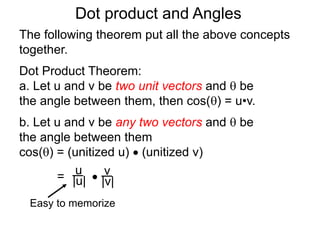

The document discusses unitizing vectors. In an example, a vector v = <3, 4> is unitized by rescaling it to obtain the unit vector <3/5, 4/5>. In general, to unitize a vector v, we divide it by its length |v| to obtain the unitized vector 1/|v| * v, which geometrically corresponds to shrinking or stretching v to have a length of 1.