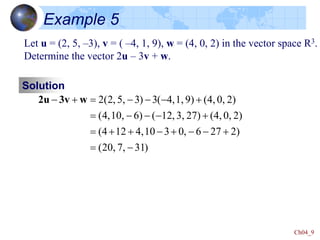

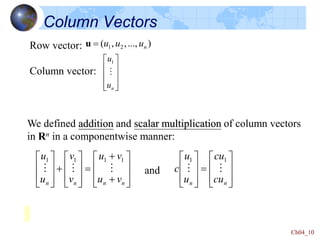

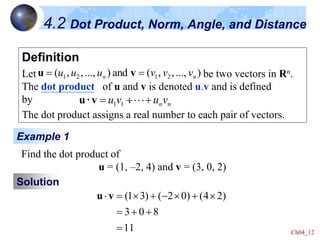

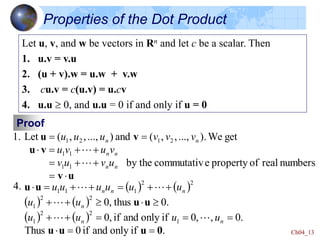

This document defines key concepts in linear algebra including vector spaces, vectors, and operations on vectors such as addition and scalar multiplication. It specifically focuses on the vector space Rn:

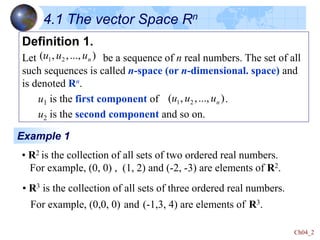

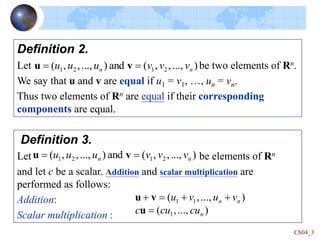

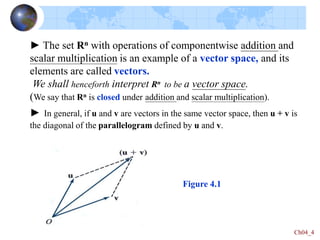

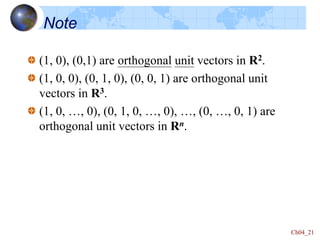

- Rn is the set of all n-tuples of real numbers, which forms a vector space under component-wise addition and scalar multiplication.

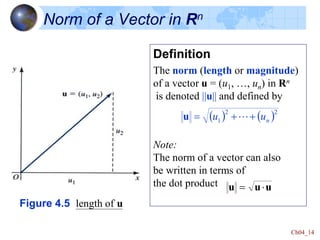

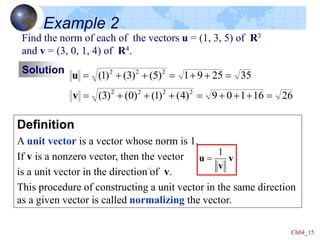

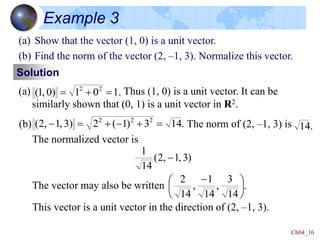

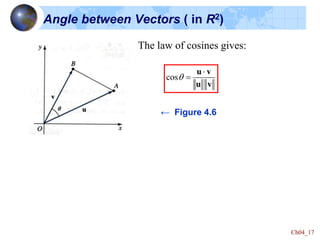

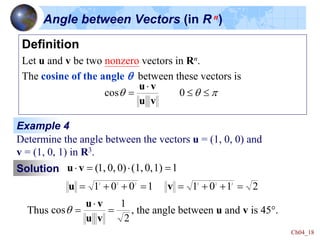

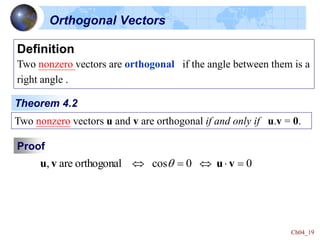

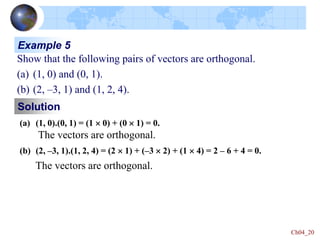

- The dot product and norm are defined for vectors in Rn and used to determine properties like orthogonality and the angle between vectors.

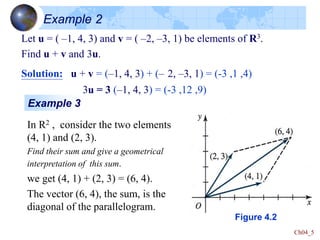

- Examples show how to perform vector operations in Rn like addition, scalar multiplication, finding the dot product and norm, and determining if vectors are orthogonal.

![Ch04_33

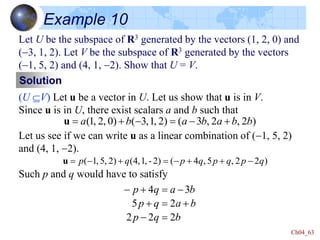

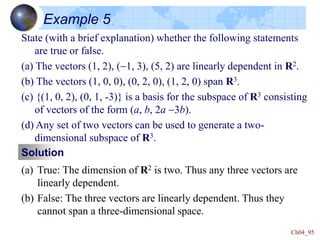

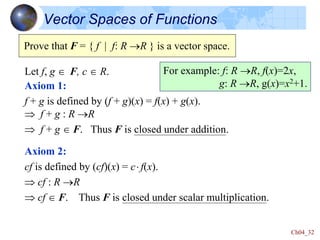

Vector Spaces of Functions (continued)

Axiom 5:

Let 0 be the function such that 0(x) = 0 for every xR.

0 is called the zero function.

We get (f + 0)(x) = f(x) + 0(x) = f(x) + 0 = f(x) for every xR.

Thus f + 0 = f. (0 is the zero vector.)

Axiom 6:

Let the function –f defined by (-f )(x) = -f (x).

Thus [f + (-f )] = 0, -f is the negative of f.

)

(

0

)]

(

[

)

(

)

)(

(

)

(

)

)](

(

[

x

x

f

x

f

x

f

x

f

x

f

f

0

-

-

-

Is the set F ={ f | f(x)=ax2+bx+c for some a,b,c R} a vector space?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mat223ch4-vectorspaces-240123071324-46fc57a3/85/Mat-223_Ch4-VectorSpaces-ppt-33-320.jpg)

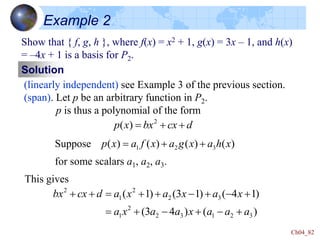

![Ch04_41

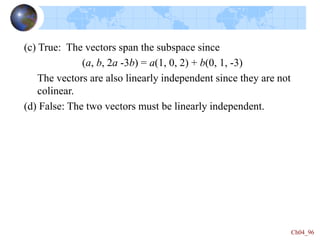

The vector space of polynomials (Pn)

Example 5. Let Pn denoted the set of real polynomial functions of

degree n. Prove that Pn is a vector space if addition and scalar

multiplication are defined on polynomials in a pointwise manner.

Solution

Let f and g Pn, where

1

1 1 0

1

1 1 0

( ) ... and

( ) ...

n n

n n

n n

n n

f x a x a x a x a

g x b x b x b x b

-

-

-

-

►(+)

(f + g)(x) is a polynomial of degree n.

Thus f + g Pn.

Then Pn is closed under addition.

)

(

)

(

...

)

(

)

(

]

...

[

]

...

[

)

(

)

(

)

)(

(

0

0

1

1

1

1

1

0

1

1

1

0

1

1

1

b

a

x

b

a

x

b

a

x

b

a

b

x

b

x

b

x

b

a

x

a

x

a

x

a

x

g

x

f

x

g

f

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Example 4.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mat223ch4-vectorspaces-240123071324-46fc57a3/85/Mat-223_Ch4-VectorSpaces-ppt-41-320.jpg)

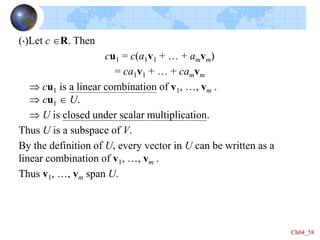

![Ch04_42

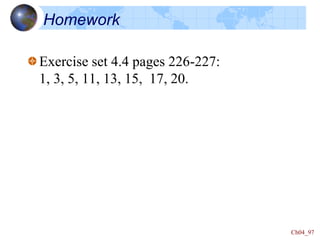

►() Let c R,

(cf )(x) is a polynomial of degree n.

So cf Pn.

Then Pn is closed under scalar multiplication.

In conclusion : By (+) and (), Pn is a subspace of the vector

space F of functions.

Therefore Pn is itself a vector space.

0

1

1

1

0

1

1

1

...

]

...

[

)]

(

[

)

)(

(

ca

x

ca

x

ca

x

ca

a

x

a

x

a

x

a

c

x

f

c

x

cf

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

-

-

-

-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mat223ch4-vectorspaces-240123071324-46fc57a3/85/Mat-223_Ch4-VectorSpaces-ppt-42-320.jpg)