The document provides a comprehensive overview of various estimation techniques in control systems, specifically focusing on different types of Kalman filters and their applications. It details the history and development of these methods, highlighting significant contributions by key figures such as Gauss and Kolmogorov. Additionally, it discusses properties of estimators and optimal parameter estimation processes in linear stationary systems.

![5

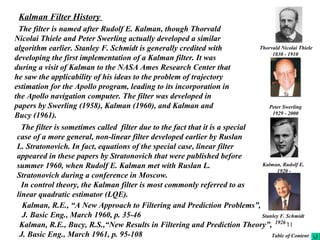

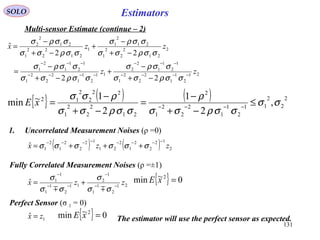

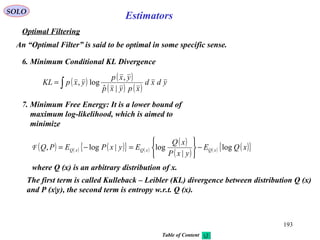

Estimators

v

( )vxh , z

x

SOLO

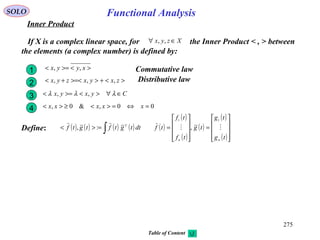

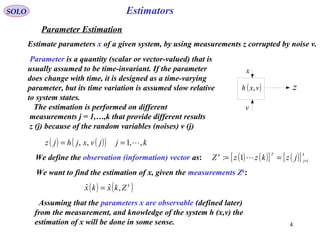

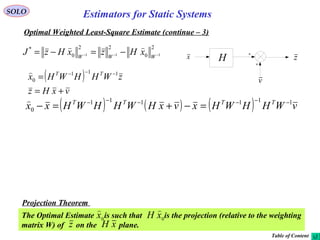

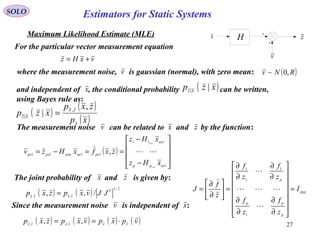

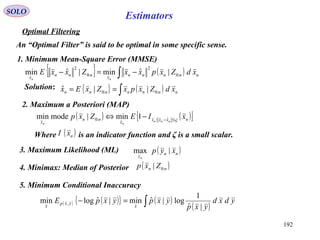

Desirable Properties of Estimators.

( ){ } ( ){ } ( )kxZkxEkxE k

== ,ˆˆ

Unbiased Estimator1

Consistent or Convergent Estimator2

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ]{ } 00ˆˆProblim =>>−−

∞→

εkxkxkxkx

T

k

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ]{ } ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ]{ } KkforkxkxkxkxEkxkxkxkxE

TT

>−−≤−− γγ ˆˆˆˆ

Efficient or Assymptotic Efficient Estimator if for All Unbiased Estimators3 ( )( )kxγγ ˆ

Sufficient Estimator if it contains all the information in the set of observed values

regarding the parameter to be observed.

4 k

Z

( )kx

Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-5-320.jpg)

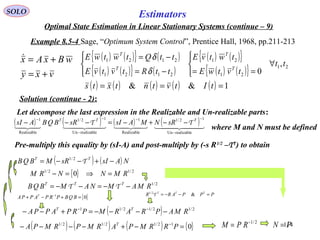

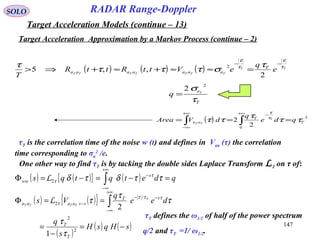

( ) ( ) 02/ 0

1

00

22

0

<−−−=−∂∂− −

xxHWHxxxxxJxx TTT

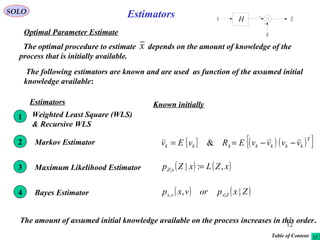

or the matrix HT

W-1

H is positive definite.

W is a hermitian (WH

= W, H stands for complex conjugate and matrix transpose),

positive definite weighting matrix.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-13-320.jpg)

![19

SOLO

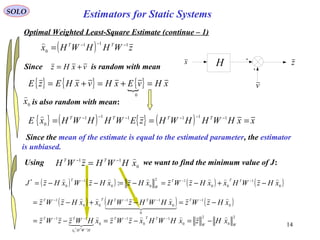

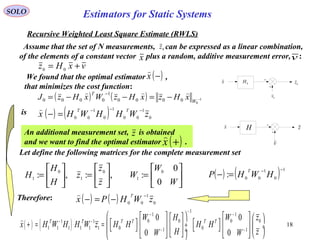

Recursive Weighted Least Square Estimate (RWLS) (continue -1)

( ) ( ) 1

0

1

00

:

−−

=− HWHP

T

( ) ( ) 0

1

00

zWHPx

T −

−=−

( ) ( ) [ ] [ ]

( ) ( )zWHzWHHWHHWH

z

z

W

W

HH

H

H

W

W

HHzWHHWHx

TTTT

TTTTTT

1

0

1

00

11

0

1

00

0

1

1

0

0

1

0

1

1

0

01

1

111

1

11

0

0

0

0

−−−−−

−

−

−

−

−

−−

++=

==+

Define ( ) ( ) HWHPHWHHWHP TTT 111

0

1

00

1

: −−−−−

+−=+=+

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )−+−−−−=+−=+

−−−−

PHWHPHHPPHWHPP TT

LemmaMatrixInverse

T 1111

( ) ( )[ ] ( )[ ] ( ) 111111 −−−−−−

+=+−≡+−− WHPWHHWHPWHPHHP TTTTT

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )−+−−=−+−−−−=+ −−

PHWHPPPHWHPHHPPP TTT 11

( ) ( )( )

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ){ } ( ) zWHPzWHPHWHPHHPP

zWHzWHPx

TTTT

TT

1

0

1

00

1

1

0

1

00

−−−

−−

++−+−−−−=

++=+

Estimators for Static Systems](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-18-320.jpg)

![20

v

H zx

SOLO

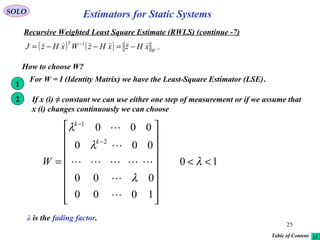

Recursive Weighted Least Square Estimate (RWLS) (continue -2)

( ) ( )( )

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ){ } ( )

( )

( )

( ) ( )[ ]

( )

( )

( )

( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) zWHPxHWHPx

zWHPzWHPHWHPHHPzWHP

zWHPzWHPHWHPHHPP

zWHzWHPx

TT

T

x

T

WHP

TT

x

T

TTTT

TT

T

11

1

0

1

00

1

0

1

00

1

0

1

00

1

1

0

1

00

1

−−

−

−

−

+

−

−

−

−−−

−−

++−+−−=

++−+−−−−=

++−+−−−−=

++=+

−

( ) ( ) 0

1

00

zWHPx

T −

−=−

( ) ( ) HWHPP T 111 −−−

+−=+

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )( )−−++−=+ −

xHzWHPxx T 1

Recursive Weighted Least Square Estimate

(RWLS)

z

( )−x

( )+x

Delay

( ) HWHP T 11 −−

=+

H

( ) 1−

+ WHP T

Estimator

Estimators for Static Systems](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-19-320.jpg)

![21

( ) ( )

( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )xHzWxHzxHzWxHz

xHz

xHz

W

W

xHzxHz

xHz

xHz

W

W

xHz

xHz

xHzWxHzJ

TT

TT

T

T

−−+−−=

−

−

−−=

−

−

−

−

=−−=

−−

−

−

−

−

1

00

1

000

00

1

1

0

00

00

1

000

11

1

1111

0

0

0

0

( ) 0

1

00

1

: HWHP

T −−

=−

SOLO

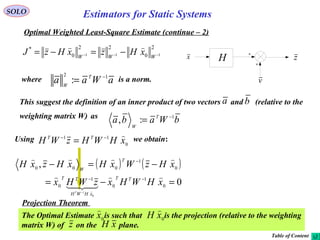

Recursive Weighted Least Square Estimate (RWLS) (continue -3)

Second Way

We want to prove that

where ( ) ( ) 0

1

00

: zWHPx

T −

−=−

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ]−−−−−=−− −−

xxPxxxHzWxHz

TT 1

00

1

000

Therefore

( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) 11

11

1 −− −+−−=−−+−−−−−= −

−−

WP

TT

xHzxxxHzWxHzxxPxxJ

Estimators for Static Systems](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-20-320.jpg)

![22

( ) 0

1

00

1

: HWHP

T −−

=−

SOLO

Recursive Weighted Least Square Estimate (RWLS) (continue -4)

Second Way (continue – 1)

We want to prove that

Define

( ) ( ) 0

1

00: zWHPx

T −

−=−

( ) ( )−=−

−

PHWzx

TT

0

1

00

( ) ( )−−= −−

xPzWH

T 1

0

1

00

( ) ( )−−= −− 1

0

1

00 PxHWz TT

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ]−−−−−=−− −−

xxPxxxHzWxHz

TT 1

00

1

000

( ) ( )

xHWHxzWHxxHWzzWz

xHzWxHz

TTTTTT

T

0

1

000

1

000

1

000

1

00

00

1

000

−−−−

−

+−−=

−−

( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )−−−+−−−−−−−=

−−−−−

−−−−

−

xPxxPxxPxxPx

xxPxx

TTTT

T

1111

1

( ) ( ) xPxxHWz TT

−−= −− 1

0

1

00

( ) ( )−−= −−

xPxzWx TTT 1

0

1

00

R

( ) xHWHxxPx

TTT

0

1

00

1 −−

=−

Estimators for Static Systems](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-21-320.jpg)

![23

( ) 0

1

00

1

: HWHP

T −−

=− ( ) ( ) 0

1

00

: zWHPx

T −

−=−

SOLO

Recursive Weighted Least Square Estimate (RWLS) (continue -5)

Second Way (continue – 2)

We want to prove that

Define

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ]−−−−−=−− −−

xxPxxxHzWxHz

TT 1

00

1

00

( ) ( )

xHWHxzWHxxHWzzWz

xHzWxHz

TTTTTT

T

0

1

000

1

000

1

000

1

00

00

1

000

−−−−

−

+−−=

−−

( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )−−−+−−−−−−−=

−−−−−

−−−−

−

xPxxPxxPxxPx

xxPxx

TTTT

T

1111

1

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) 0

1

00

1

0

1

00

1

zWHPHWzxPx

TTT −−−−

−=−−−

Use the identity: ( )

1

00

1

0

1

00

1

0

1

000

1

0

1

0

1

−

−−−−−−

+≡+−

TTT

HIHWWHIHWHHWW

ε

ε

( ) 0lim

1

lim

1

lim

1

00

0

1

00

0

1

00

1

0

0

1

0 ==

=

+−

−

→

−

→

−

−

→

− TTT

HHHHHIHWW ε

εε εεε

( ) ( ) 1

00

1

0

1

0

1

00

1

0

1

000

1

0

1

0

−−−−−−−−

−== WHPHWWHHWHHWW

TTT

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) 0

1

000

1

00

1

0

1

00

1

zWzzWHPHWzxPx

TTTT −−−−−

=−=−−−

q.e.d.

Estimators for Static Systems](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-22-320.jpg)

![24

( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )xHzWxHzxxPxxJ

TT

−−+−−−−−= −− 11

1

SOLO

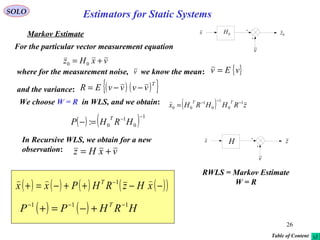

Recursive Weighted Least Square Estimate (RWLS) (continue -6)

Second Way (continue – 5)

x

Choose that minimizes the scalar cost function

Solution

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) 022 *1*11

=−−−−−=

∂

∂ −−

xHzWHxxP

x

J T

T

Define: ( ) ( ) HWHPP T 111

: −−−

+−=+

Then:

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]−−+−+=+−−+=+ −−−−−−

xHzWHxPzWHxHWHPxP TTT 11111*1

( )[ ] ( ) ( ) zWHxPxHWHP TT 11*11 −−−−

+−−=+−

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]−−++−=+= −

xHzWHPxxx T 1*

( )[ ] ( )+=+−=

∂

∂ −−− 111

2

1

2

22 PHWHP

x

J T

T

If P-1

(+) is a positive definite matrix then is a minimum solution.*

x

Estimators for Static Systems](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-23-320.jpg)

![28

SOLO

Maximum Likelihood Estimate (continue – 1)

v

H zx

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )vpxpvxpzxp vxvxzx ⋅== ,, ,,

x

v

( )vxp vx

,,

( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( )

−−−=

−=

−

xHzRxHz

R

xHzpxzp

T

p

vxz

1

2/12/

|

2

1

exp

2

1

|

π

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )RWWLSxHzRxHzxzp

T

x

xz

x

⇒−−⇔ −1

| min|max

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) 02 11

=−−=−−

∂

∂ −−

xHzRHxHzRxHz

x

TT

0*11

=− −−

xHRHzRH TT

( ) zRHHRHxx TT 111

*: −−−

==

( ) ( )[ ] HRHxHzRxHz

x

TT 11

2

2

2 −−

=−−

∂

∂ this is a positive definite matrix, therefore

the solution minimizes

and maximizes

( ) ( )[ ]xHzRxHz

T

−− −1

( )xzp xz ||

( ) ( )

( )

( )

( )

−=== −

vRv

R

vp

xp

zxp

xzp T

pv

x

zx

xz

1

2/12/

/

|

2

1

exp

2

1,

|

π

Gaussian (normal), with zero mean

( ) ( )xzpxzL xz |:, |=

is called the Likelihood Function and is a measure

of how likely is the parameter given the observation .x z

Estimators for Static Systems](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-27-320.jpg)

![30

SOLO

Bayesian Maximum Likelihood Estimate (Maximum Aposterior – MAP Estimate)

v

H zx

vxHz +=

Consider a gaussian vector , where ,

measurement, , where the Gaussian noise

is independent of and .( )Rv ,0~ N

v

x ( ) ( )[ ]−− Pxx ,~

N

x

( )

( ) ( )

( )( ) ( ) ( )( )

−−−−−−

−

= −

xxPxx

P

xp

T

nx

1

2/12/

2

1

exp

2

1

π

( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( )

−−−=−= −

xHzRxHz

R

xHzpxzp

T

pvxz

1

2/12/|

2

1

exp

2

1

|

π

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∫∫

+∞

∞−

+∞

∞−

== xdxpxzpxdzxpzp xxzzxz |, |,

is Gaussian with( )zpz ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )−=+=+= xHvExEHvxHEzE

0

( ) ( )[ ] ( )[ ]{ } ( )[ ] ( )[ ]{ }

( )( )[ ] ( )( )[ ]{ } ( )[ ] ( )[ ]{ }

( )[ ]{ } ( )[ ]{ } { } ( ) RHPHvvEHxxvEvxxEH

HxxxxEHvxxHvxxHE

xHvxHxHvxHEzEzzEzEz

TTTTT

TTT

TT

+−=+−−−−−−

−−−−=+−−+−−=

−−+−−+=−−=

00

cov

( )

( ) ( )

( )[ ] ( )[ ] ( )[ ]

−−+−−−−

+−

=

−

xHzRHPHxHz

RHPH

zp TT

Tpz

ˆˆ

2

1

exp

2

1 1

2/12/

π

Estimators for Static Systems](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-29-320.jpg)

![31

SOLO

Bayesian Maximum Likelihood Estimate (Maximum Aposterior Estimate) (continue – 1)

v

H zx

vxHz +=

Consider a Gaussian vector , where ,

measurement, , where the Gaussian noise

is independent of and .( )Rvv ,0;~ N

v

x ( ) ( )[ ]−− Pxxx ,;~

N

x

( )

( ) ( )

( )( ) ( ) ( )( )

−−−−−−

−

= −

xxPxx

P

xp

T

nx

1

2/12/

2

1

exp

2

1

π

( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( )

−−−=−= −

xHzRxHz

R

xHzpxzp

T

pvxz

1

2/12/|

2

1

exp

2

1

|

π

( )

( ) ( )

( )[ ] ( )[ ] ( )[ ]

−−+−−−−

+−

=

−

xHzRHPHxHz

RHPH

zp TT

Tpz

ˆˆ

2

1

exp

2

1 1

2/12/

π

( )

( ) ( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( ) ( ) ( )( ) ( ) ( )( ) ( )[ ] ( )[ ] ( )[ ]

−−+−−−+−−−−−−−−−⋅

+−

−

==

−−−

xHzRHPHxHzxxPxxxHzRxHz

RHPH

RPzp

xpxzp

zxp

TTTT

T

nz

xxz

zx

ˆˆ

2

1

2

1

2

1

exp

2

1|

|

111

2/1

2/12/1

2/

|

|

π

from which

Estimators for Static Systems](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-30-320.jpg)

![32

SOLO

Bayesian Maximum Likelihood Estimate (Maximum Aposterior Estimate) (continue – 2)

( ) ( ) ( )( ) ( ) ( )( ) ( )( ) ( )[ ] ( )( )−−+−−−−−−−−−+−−

−−−

xHzRHPHxHzxxPxxxHzRxHz TTTT 111

( ) ( )( )[ ] ( ) ( )( )[ ] ( )( ) ( ) ( )( )

( )( ) ( )[ ] ( )( ) ( )( ) ( )[ ]{ } ( )( )

( )( ) ( )( ) ( )( ) ( )( ) ( )( ) ( )[ ] ( )( )−−+−−−+−−−−−−−−−−

−−+−−−−=−−+−−−−

−−−−−+−−−−−−−−−−=

−−−−

−−−

−−

xxHRHPxxxxHRxHzxHzRHxx

xHzRHPHRxHzxHzRHPHxHz

xxPxxxxHxHzRxxHxHz

TTTTT

TTTT

TT

1111

111

11

( )( ) ( )( ) ( )( ) ( ) ( )( ) ( )( ) ( )[ ] ( )( )−−+−−−−−−−−−+−−−−

−−−

xHzRHPHxHzxxPxxxHzRxHz TTTT 111

( )[ ] ( )[ ] 11111111 −−−−−−−−

−++/−/=+−− RHPHRHHRRRRHPHR TTT

we have

then

Define: ( ) ( )[ ] 111

:

−−−

+−=+ HRHPP T

( )( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )( )

( )( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )( ) ( )( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )( )

( )( ) ( )[ ] ( )( )−−+−−−+

−−++−−−−−++−−−

−−+++−−=

−−

−−−−

−−−

xxHRHPxx

xxPPHRxHzxHzRHPPxx

xHzRHPPPHRxHz

TT

TTT

TT

11

1111

111

( ) ( ) ( )( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )( )[ ]−−++−−+−−++−−= −−−

xHzRHPxxPxHzRHPxx TTT 111

( )

( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( )( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )( )[ ]

−−+−−−+−−+−−−−⋅

+

= −−−

xHzRHPxxPxHzRHPxx

P

zxp TTT

nzx

111

2/12/|

2

1

exp

2

1

|

π

Estimators for Static Systems](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-31-320.jpg)

![33

SOLO

Bayesian Maximum Likelihood Estimate (Maximum Aposterior Estimate) (continue – 3)

then

where: ( ) ( )[ ] 111

:

−−−

+−=+ HRHPP T

( )

( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

−+−−−+−+−−−−⋅

+

= −−−

xHzRHPxxPxHzRHPxx

P

zxp TTT

nzx

111

2/12/|

2

1

exp

2

1

|

π

( )zxp zx

x

|max | ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )( )−−++−==+ −

xHzRHPxxx T 1*

:

Table of Content

Estimators for Static Systems](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-32-320.jpg)

[ ]( ){ } { } { } { }TTT

x xExExxExExxExE

−=−−=

2

σ - estimated variance matrix

For a good estimator we want

{ } xxE =

- unbiased estimator vector

{ } { } { }TT

x xExExxE

−=

2

σ - minimum estimation variance

( ) ( ){ }Tk

kzzZ 1:= - the observation matrix after k observations

( ) ( ) ( ){ }xkzzLxZL k

,,,1, = - the Likelihood or the joint density function of Zk

We have:

( )T

pzzzz ,,, 21 = ( )T

n

xxxx ,,, 21

= ( )T

pvvvv ,,, 21 =

The estimation of , using the measurements

of a system corrupted by noise is a random variable with

xˆ x z

v

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∫== dvvpxvZpxZpxZL v

k

vz

k

xz

k

;||, ||

( ) ( )[ ]{ } ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )

[ ] [ ] ( )xbxZdxZLZx

kzdzdxkzzLkzzxkzzxE

kkk

+==

=

∫

∫

,

1,,,1,,1,,1

- estimator bias( )xb

therefore:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-33-320.jpg)

![35

Estimators

v

( )vxh ,

z

x

Estimator

x

SOLO

The Cramér-Rao Lower Bound on the Variance of the Estimator (continue – 1)

[ ]{ } [ ] [ ] ( )xbxZdxZLZxZxE kkkk

+== ∫ ,

We have:

[ ]{ } [ ] [ ] ( )

x

xb

Zd

x

xZL

Zx

x

ZxE k

k

k

k

∂

∂

+=

∂

∂

=

∂

∂

∫ 1

,

Since L [Zk

,x] is a joint density function, we have:

[ ] 1, =∫

kk

ZdxZL

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ]0

,,

0

,

=

∂

∂

=

∂

∂

→=

∂

∂

∫∫∫

k

k

k

k

k

k

Zd

x

xZL

xZd

x

xZL

xZd

x

xZL

[ ]( ) [ ] ( )

x

xb

Zd

x

xZL

xZx k

k

k

∂

∂

+=

∂

∂

−∫ 1

,

Using the fact that: [ ] [ ] [ ]

x

xZL

xZL

x

xZL k

k

k

∂

∂

=

∂

∂ ,ln

,

,

[ ]( ) [ ] [ ] ( )

x

xb

Zd

x

xZL

xZLxZx k

k

kk

∂

∂

+=

∂

∂

−∫ 1

,ln

,

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-34-320.jpg)

[ ] [ ] ( )

x

xb

Zd

x

xZL

xZLxZx k

k

kk

∂

∂

+=

∂

∂

−∫ 1

,ln

,

Hermann Amandus

Schwarz

1843 - 1921

Let use Schwarz Inequality:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∫∫∫ ≤ dttgdttfdttgtf

22

2

The equality occurs if and only if f (t) = k g (t)

[ ]( ) [ ] [ ] [ ]xZL

x

xZL

gxZLxZxf k

k

kk

,

,ln

:&,:

∂

∂

=−=

choose:

[ ]( ) [ ] [ ]

( ) [ ]( ) [ ]( ) [ ] [ ]

∂

∂

−≤

∂

∂

+=

∂

∂

−

∫∫

∫

k

k

kkkk

k

k

kk

Zd

x

xZL

xZLZdxZLxZx

x

xb

Zd

x

xZL

xZLxZx

2

2

2

2

,ln

,,1

,ln

,

[ ]( ) [ ]

( )

[ ] [ ]

∫

∫

∂

∂

∂

∂

+

≥−

k

k

k

kkk

Zd

x

xZL

xZL

x

xb

ZdxZLxZx 2

2

2

,ln

,

1

,

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-35-320.jpg)

[ ]

( )

[ ] [ ]

∫

∫

∂

∂

∂

∂

+

≥−

k

k

k

kkk

Zd

x

xZL

xZL

x

xb

ZdxZLxZx 2

2

2

,ln

,

1

,

This is the Cramér-Rao bound for a biased estimator

Harald Cramér

1893–1985

Cayampudi Radhakrishna

Rao

1920 -

[ ]{ } ( ) [ ] 1,& =+= ∫

kkk

ZdxZLxbxZxE

[ ]( ) [ ] [ ] [ ]{ } ( )( ) [ ]

[ ] [ ]{ }( ) [ ] ( ) [ ] [ ]{ }( ) [ ]

( ) [ ]

1

2

0

2

22

,

,2,

,,

∫

∫∫

∫∫

+

−+−=

+−=−

kk

kkkkkkkk

kkkkkkk

ZdxZLxb

ZdxZLZxEZxxbZdxZLZxEZx

ZdxZLxbZxEZxZdxZLxZx

[ ] [ ]{ }( ) [ ]

( )

[ ] [ ]

( )xb

Zd

x

xZL

xZL

x

xb

ZdxZLZxEZx

k

k

k

kkkk

x

2

2

2

22

,ln

,

1

, −

∂

∂

∂

∂

+

≥−=

∫

∫

σ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-36-320.jpg)

![38

EstimatorsSOLO

The Cramér-Rao Lower Bound on the Variance of the Estimator (continue – 4)

[ ] [ ]{ }( ) [ ]

( )

[ ] [ ]

( )xb

Zd

x

xZL

xZL

x

xb

ZdxZLZxEZx

k

k

k

kkkk

x

2

2

2

22

,ln

,

1

, −

∂

∂

∂

∂

+

≥−=

∫

∫

σ

[ ] [ ]

[ ]

[ ]

[ ] [ ] [ ] 0,

,ln

0

,

1,

,

,

,ln

=

∂

∂

→=

∂

∂

→= ∫∫∫

∂

∂

=

∂

∂

kk

kxZL

x

xZL

x

xZL

k

k

kk

ZdxZL

x

xZL

Zd

x

xZL

ZdxZL

k

k

k

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ]

[ ]

0,

,ln,ln

,

,ln

,

2

2

=

∂

∂

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

→ ∫∫

∂

∂

∂

∂

k

x

xZL

k

kk

kk

kx

ZdxZL

x

xZL

x

xZL

ZdxZL

x

xZL

k

[ ] [ ] 0

,ln,ln

2

2

2

=

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

→

∂

∂

x

xZL

E

x

xZL

E

kkx

( )

[ ]

( )

( )

[ ]

( )xb

x

xZL

E

x

xb

xb

x

xZL

E

x

xb

k

k

x

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

,ln

1

,ln

1

−

∂

∂

∂

∂

+

−=−

∂

∂

∂

∂

+

≥σ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-37-320.jpg)

[ ]

( )

[ ]

( )

[ ]

∂

∂

∂

∂

+

−=

∂

∂

∂

∂

+

≥−∫

2

2

2

2

2

2

,ln

1

,ln

1

,

x

xZL

E

x

xb

x

xZL

E

x

xb

ZdxZLxZx kk

kkk

SOLO

The Cramér-Rao Lower Bound on the Variance of the Estimator (continue – 5)

( )

[ ]

( )

( )

[ ]

( )xb

x

xZL

E

x

xb

xb

x

xZL

E

x

xb

k

k

x

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

,ln

1

,ln

1

−

∂

∂

∂

∂

+

−=−

∂

∂

∂

∂

+

≥σ

For an unbiased estimator (b (x) = 0), we have:

[ ] [ ]

∂

∂

−=

∂

∂

≥

2

22

2

,ln

1

,ln

1

x

xZL

E

x

xZL

E

k

k

x

σ

http://www.york.ac.uk/depts/maths/histstat/people/cramer.gif](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-38-320.jpg)

[ ]( ) [ ] [ ]( ) [ ]( ){ }

( ) [ ] [ ] ( )

( ) [ ] ( )

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

∂

∂

+−=

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

∂

+≥

−−=−−

−

−

∫

x

xb

I

x

xZL

E

x

xb

I

x

xb

I

x

xZL

x

xZL

E

x

xb

I

xZxxZxEZdxZLxZxxZx

x

k

T

x

T

kk

T

x

TkkkkTkk

1

2

2

1

,ln

,ln,ln

,

SOLO

The Cramér-Rao Lower Bound on the Variance of the Estimator (continue – 5)

The multivariable form of the Cramér-Rao Lower Bound is:

[ ]( )

[ ]

[ ]

−

−

=−

n

k

n

k

k

xZx

xZx

xZx

11

[ ]( ) [ ]

[ ]

[ ]

∂

∂

∂

∂

=

∂

∂

=∇

n

k

k

k

k

x

x

xZL

x

xZL

x

xZL

xZL

,ln

,ln

,ln

,ln

1

Fisher Information Matrix

[ ] [ ] [ ]

∂

∂

−=

∂

∂

∂

∂

=

x

k

x

T

kk

x

xZL

E

x

xZL

x

xZL

E 2

2

,ln,ln,ln

:J

Fisher, Sir Ronald Aylmer

1890 - 1962](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-39-320.jpg)

[ ]( ){ } [ ]( ){ }x

k

xx

x

Tk

x

k

x

xZLExZLxZLEx ,ln,ln,ln: ∇∇−=∇∇=J

Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-40-320.jpg)

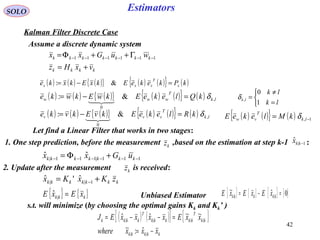

![43

Estimators

kkkkk xxx −= −− 1|1|

ˆ:~

kkkkkkk zKxKx += −1||

ˆ'ˆ

SOLO

Kalman Filter Discrete Case (continue – 1)

Define

kkkkk xxx −= ||

ˆ:~

The Linear Estimator we want is:

Therefore

[ ] [ ] [ ] kkkkkkkkk

z

kkkk

x

kkkkkkk vKxKxIHKKvxHKxxKxx

kkk

++−+=++++−= −−

−

1|

ˆ

1||

~''~'~

1|

Unbiaseness conditions: { } { } 0~~

1|| == −kkkk xExE

gives: { } [ ] { } { } { } 0~''~

00

1|

0

| =++−+= −

kkkkkkkkkkk vEKxEKxEIHKKxE

or: kkk HKIK −='

Therefore the Unbiased Linear Estimator is:

[ ]1|1||

ˆˆˆ −− −+= kkkkkkkkk xHzKxx](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-42-320.jpg)

![44

Estimators

+=

Γ++Φ= −−−−−−

kkkk

kkkkkkk

vxHz

wuGxx 111111

SOLO

Kalman Filter Discrete Case (continue – 2)

The discrete dynamic system

The Linear Filter

(Linear Observer)[ ]

−++=

+Φ=

−−−−

−−−−−−

1|111||

111|111|

ˆˆˆ

ˆˆ

kkkkkkkkkkk

kkkkkkk

xHzKuGxx

uGxx

111|111|1|

~ˆ:~

−−−−−−− Γ−Φ=−= kkkkkkkkkk wxxxx

{ } T

kkk

T

kkkk

T

kkkkkk QPxxEP 11111|111|1|1|

~~: −−−−−−−−−− ΓΓ+ΦΦ==

{ } { } { }

{ } { } { } { }

{ } { } { }0~

00

0~~

1111

1

1||

==

==

==

−−−−

−

−

T

kk

T

kk

kk

kkkk

wxEwxE

wEvE

xExE

{ }

[ ] [ ]{ }

{ } { }

{ } { } T

k

T

kkk

T

k

T

kkk

T

k

T

kkk

T

k

T

kkk

T

k

T

k

T

k

T

kkkkk

T

kkkkkk

wwExwE

wxExxE

wxwxE

xxEP

11111

0

111

1

0

1111111

11111111

1|1|1|

~

~~~

~~

~~:

−−−−−−−−

−−−−−−−−

−−−−−−−−

−−−

ΓΓ+ΦΓ−

ΓΦ−ΦΦ=

Γ−ΦΓ−Φ=

=

{ } { } { } 1111

0

1|111|

1

~~

−−−−−−−− Γ−=Γ−Φ=

−

kk

M

T

kkkkkkk

T

kkk MvwEvxEvxE

k

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-43-320.jpg)

![45

EstimatorsSOLO

Kalman Filter Discrete Case (continue – 3)

{ }kkkkkkkkkkkk vxHKxxxx −−=−= −− 1|1|||

~~ˆ:~

{ } ( )[ ] ( )[ ]{ }T

k

T

k

T

k

T

kk

T

kkkkkkkkk

T

kkkkkk KvHxxvxHKxExxEP −−−−== −−−− 1|1|1|1||||

~~~~~~:

{ } 111|

~

−−− Γ−= kk

T

kkk MvxE

( ) { }( ) { }[ ]

{ }( ) { }[ ]T

k

T

kkk

T

k

T

k

T

kkkk

T

k

T

kkk

T

k

T

k

T

kkkkkk

KxvEKHIxvEK

KvxEKHIxxEHKI

1|1|

1|1|1|

~~

~~~

−−

−−−

+−+

+−−=

( ) { } ( ) { }

( ) ( )T

kk

T

k

T

kk

T

kkkkk

T

k

R

T

kkk

T

kk

P

T

kkkkkk

HKIMKKMHKI

KvvEKHKIxxEHKI

kkk

−Γ−Γ−−

+−−=

−−−−

−−

−

1111

1|1|

1|

~~

+=

Γ++Φ= −−−−−−

kkkk

kkkkkkk

vxHz

wuGxx 111111

The discrete dynamic system

The Linear Filter

(Linear Observer)[ ]

−++=

+Φ=

−−−−

−−−−−−

1|111||

111|111|

ˆˆˆ

ˆˆ

kkkkkkkkkkk

kkkkkkk

xHzKuGxx

uGxx](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-44-320.jpg)

![46

EstimatorsSOLO

Kalman Filter Discrete Case (continue – 4)

{ }

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )T

kk

T

k

T

kk

T

kkkkk

T

kkk

T

kkkkkk

T

kkkkkk

HKIMKKMHKIKRKHKIPHKI

xxEP

−Γ−Γ−−+−−=

=

−−−−− 11111|

|||

~~:

{ } ( ) ( )

( ) T

k

T

kkkk

T

k

T

k

T

kkkkkk

T

k

T

kkkkk

T

kkk

T

kkkkk

T

kkkkkk

KHPHHMMHRK

MPHKKMHPPxxEP

1|1111

111|111|1||||

~~:

−−−−−

−−−−−−−

+Γ+Γ++

Γ+−Γ+−==

Completion of Squares

[ ]

[ ]

[ ] [ ]

+Γ+Γ+Γ+−

Γ+−

=

−−−−−−−−

−−−−

T

k

C

T

kkkk

T

k

T

k

T

kkkkk

B

T

k

T

kkkk

B

kk

T

kkk

A

kk

kkk

K

I

HPHHMMHRMPH

MHPP

KIP

T

1|1111111|

111|1|

|

Joseph Form (true for all Kk)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-45-320.jpg)

![47

Estimators

{ } { } kk

K

T

kk

K

k

T

k

K

k

K

PtracexxEtracexxEJ

kkkk

|min~~min~~minmin ===

SOLO

Kalman Filter Discrete Case (continue – 5)

Completion of Squares

Use the Matrix Identity:

−

−

−

=

−

−

−

∆

−

−

IBC

I

C

BCBA

I

CBI

CB

BA

T

T

T 1

1

1

0

0

0

0

{ } [ ] [ ] ( )

−

+Γ+Γ+

∆

−== −

−−−−−

−

T

k

T

kkkk

T

k

T

k

T

kkkkk

k

k

T

kkkkkk

CBK

I

HPHHMMHR

CBKIxxEP 1

1|1111

1

|||

0

0

~~:

to obtain

( ) ( ) ( )T

k

T

kkkk

T

kkkk

T

k

T

k

T

kkkkkkk

T

kkkkkk MPHHPHHMMHRMHPP 111|

1

1|1111111|1|: −−−

−

−−−−−−−−− Γ++Γ+Γ+Γ+−=∆

[ ]

[ ]

[ ] [ ]

+Γ+Γ+Γ+−

Γ+−

=

−−−−−−−−

−−−−

T

k

C

T

kkkk

T

k

T

k

T

kkkkk

B

T

k

T

kkkk

B

kk

T

kkk

A

kk

kkk

K

I

HPHHMMHRMPH

MHPP

KIP

T

1|1111111|

111|1|

|](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-46-320.jpg)

![48

Estimators

{ } { } kk

T

kkkkkk

T

kkk PtracexxEtracexxEJ |||||

~~~~ ===

[ ][ ]

1

1

1|1111111|

..*

−

−

−−−−−−−− +Γ+Γ+Γ+==

C

T

kkkk

T

k

T

k

T

kkkkk

B

kk

T

kkk

FK

kk HPHHMMHRMHPKK

SOLO

Kalman Filter Discrete Case (continue – 6)

To obtain the optimal K (k) that minimizes J (k+1) we perform

[ ] [ ]{ } 011|

=−−+∆

∂

∂

=

∂

∂

=

∂

∂ −− T

kkk

kk

kk

k

k

CBKCCBKtrace

KK

Ptrace

K

J

Using the Matrix Equation: (see next slide){ } ( )TT

BBAABAtrace

A

+=

∂

∂

[ ]( ) 01*|

=+−=

∂

∂

=

∂

∂ − T

k

k

kk

k

k

CCCBK

K

Ptrace

K

J

we obtain

or

Kalman Filter Gain

( ) ( )( ) ( )

( ){ }T

kk

T

kkkkkk

B

T

kk

T

kkk

C

T

kkkk

T

k

T

k

T

kkkkk

B

kk

T

kkk

A

kkkkk

K

MHPKPtrace

MHPHPHHMMHRMHPPtracetracePtracekJ

T

111|1|

111|

1

1|1111111|1||min

1

min

−−−−

−−−

−

−−−−−−−−−

Γ+−=

Γ++Γ+Γ+Γ+−=∆==

−

( ) [ ]T

kkkk

T

k

T

k

T

kkkkk

T

k

kk

k

k

HPHHMMHRCC

K

Ptrace

K

J

1|11112

|

2

2

2

2 −−−−− +Γ+Γ+=+=

∂

∂

=

∂

∂](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-47-320.jpg)

![49

MatricesSOLO

Differentiation of the Trace of a square matrix

[ ] ( )

( )

∑∑∑∑∑∑

=

==

l p k

lkpklp

aa

l p k

T

klpklp

T

abaabaABAtrace

lk

T

kl

[ ]T

ABAtrace

A∂

∂

[ ] ∑∑ +=

∂

∂

p

pjip

k

ikjk

T

ij

baabABAtrace

a

[ ] ( )TTT

BBABABAABAtrace

A

+=+=

∂

∂](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-48-320.jpg)

![50

Estimators

( ) 1

1|1|*

−

−− +=

T

kkkkk

T

kkkk HPHRHPK

( ) ( ) T

kkk

T

kkkkkkkk KRKHKIPHKIP ***** 1|| +−−= −

SOLO

Kalman Filter Discrete Case (continue – 7)

we found that the optimal Kk that minimizes Jk is

( ) 1|

1

1|1|1| −

−

−−− +−= kkk

T

kkkkk

T

kkkkk PHHPHRHPP

( ) [ ] 1|

111

1|

&

*11 −

−−−

− −=+=−− kkkkkk

T

kkk

LemmaMatrixInverse

existRP

PHKIHRHP

kk

When Mk = 0, where:

( ) ( ){ } 1, −= lkk

T

vw MlekeE δ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-49-320.jpg)

![51

Estimators

SOLO

Kalman Filter Discrete Case (continue – 8)

We found that the optimal Kk that minimizes Jk (when Mk-1 = 0 ) is

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] 1

1|1111|11*

−

+++++++=+ kHkkPkHkRkHkkPkK TT

( ) ( ) 1111

1|

11

&

1

1| 1

1|

1

−−−−

−

−−−

− +−=+ −

−

− k

T

kkk

T

kkkkkk

LemmaMatrixInverse

existPR

T

kkkkk RHHRHPHRRHPHR

kkk

( ) 1111

1|

1

1|

1

1|*

−−−−

−

−

−

−

− +−= k

T

kkk

T

kkkkk

T

kkkk

T

kkkk RHHRHPHRHPRHPK

( ){ } ( ) 1111

1|

111

1|1|

−−−−

−

−−−

−− +−+= k

T

kkk

T

kkkkk

T

kkk

T

kkkkk RHHRHPHRHHRHPP

[ ] 1

1|

1111

1|*

−

−

−−−−

− =+= k

T

kkkk

T

kkk

T

kkkk RHPRHHRHPK

If Rk

-1

and Pk|k-1

-1

exist:

Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-50-320.jpg)

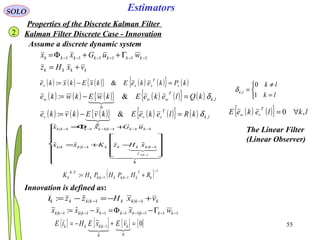

![52

Estimators

SOLO

Kalman Filter Discrete Case (continue – 9)

Properties of the Kalman Filter

{ } 0~ˆ || =

T

kkkk xxE

Proof (by induction):

( )

1111

00000001 0

vxHz

xxwuGxx

+=

=Γ++Φ=k=1:

( ) { }

( )

( )0010|00110010010011000|00

0010|0011111000|00

00|00|1111000|001|1

ˆˆ

ˆˆ

ˆˆˆˆ

uGHxHvwHuGHxHKuGx

uGHxHvxHKuGx

xExxHzKuGxx

−Φ−+Γ++Φ++Φ=

−Φ−+++Φ=

=−++Φ=

( ) 1100110|00110|0011|11|1

~~ˆ~ vKwIHKxHKxxxx +Γ−+Φ−Φ=−=

{ } ( )[ ]{ 100110|001000|001|11|1

~ˆ~ˆ vwHKxKuGxExxE

T

+Γ+Φ−+Φ=

( )[ ] }T

vKwIHKxHKx 1100110|00110|00

~~ +Γ−+Φ−Φ

{ }( ) { } ( )

{ } T

R

T

TTT

Q

TTT

P

T

KvvEK

IKHwwEHKHKIxxEHK

1111

110000110110|00|0011

1

00|0

~~

+

−ΓΓ+Φ−Φ−=

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-51-320.jpg)

![53

Estimators

SOLO

Kalman Filter Discrete Case (continue – 10)

Properties of the Discrete Kalman Filter

{ } 0~ˆ || =

T

kkkk xxE

Proof (by induction) (continue – 1):

k=1 :

{ } ( ) ( ) TTTTTTT

KRKIKHQHKHKIPHKxxE 11111000110110|00111|11|1

~ˆ +−ΓΓ+Φ−Φ−=

1

( ) ( ) TTT

P

TT

P

TT

KRKKHQPHKQPHK 1111100000|001100000|0011

0|10|1

+ΓΓ+ΦΦ+ΓΓ+ΦΦ−=

[ ] [ ] 0

1

111|11

1|1

111|111111110|111

−

=

=+−=+−−=

RHPK

TTT

P

TT

T

T

KRPHKKRKKHIPHK

In the same way we continue for k > 1 and by induction we prove the result.

Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-52-320.jpg)

{ }

( ) { } ( ) { } { } { }

jkkR

T

jkk

T

j

jk

T

jkk

jk

T

jkkkk

T

j

T

jkkkk

T

jjjkkkkkkjkk

vvEKHxvEKvxEHKIHxxEHKI

vxHvKxHKIEzxE

,00

1|1|

1||

~~

~~

δ

++−+−=

++−=

→>→>

−−

−

{ } ( )[ ]{ } ( ) { } { }

0

1|1||

~~~

→>

−− +−=+−=

jk

T

jkk

T

jkkkk

T

jkkkkkk

T

jkk zvEKzxEHKIzvKxHKIEzxE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-53-320.jpg)

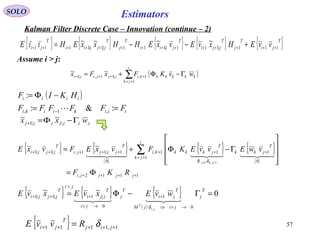

![56

Estimators

( )

[ ]

( )∑+=

+−++−

−−−−−−−−

−+

Γ−Φ+=

=

Γ−Φ+Γ−Φ+=

Γ−Φ+−Φ=Γ−Φ=

++

i

jk

kkkkk

F

kiijj

F

jii

iiiiiiiiiiiiii

iiiiiii

F

iiiiiiiiii

wvKFFFxFFF

wvKwvKxFF

wvKxHKIwxx

kiji

i

1

11|111

111112|11

1|||1

1,1,

~

~

~~~

SOLO

Kalman Filter Discrete Case – Innovation (continue – 1)

Assume i > j:

{ } { } { }

{ }

{ }

{ }

∑+=

→+≥

+

→+≥

++

+

+++++

Γ−Φ+=

i

jk

jk

T

jjkk

jk

T

jjkkkki

jPj

T

jjjjji

T

jjji xwExvEKFxxEFxxE

1

01

|1

01

|11,

|1

|1|11,|1|1

~~~~~~

( )

iiikiiki

iiii

FFFFFF

HKIF

==

−Φ=

− :&:

:

,1,

( ) ( ) iiiiiiiiiiiiiii vKxHKIvxHKxx +−=−−= −−− 1|1|1||

~~~~

{ } ( )( ){ }T

j

T

j

T

jjiiii

T

ji vHxvxHEE +−+−= −− 1|1|

~~ιι

{ } { } { } { }T

ji

T

j

T

jji

T

jiii

T

j

T

jjiii vvEHxvEvxEHHxxEH +−−= −−−− 1|1|1|1|

~~~~

jjjjjjj wxx Γ−Φ=+ ||1

~~

{ } jjji

T

jjji PFxxE |11,|1|1

~~

++++ =](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-55-320.jpg)

![58

Estimators

[ ] 1

11|111|11

.. −

+++++++ += j

T

jjjj

T

jjj

K

j RHPHHPK

FK

SOLO

Kalman Filter Discrete Case – Innovation (continue – 3)

Assume i > j:

1,111112,111|11,1 +++++++++++++ +Φ−+= jijjjjjiii

T

jjjjii RRKFHHHPFH δ

{ } { } { } { } { }T

ji

T

j

T

jji

T

jiii

T

j

T

jjiii

T

ji vvEHxvEvxEHHxxEHE 111|111|111|1|1111

~~~~

++++++++++++++ +−−=ιι

( )1112,12,1, +++++++ −Φ== jjjjijjiji HKIFFFF

( ){ } 1,11111|11112,1 ++++++++++++ +−−Φ= jijjj

T

jjjjjjjii RRKHPHKIFH δ

{ [ ]}

1,11

1,1111|1111|112,1

+++

+++++++++++++

=

++−Φ=

jij

jijj

T

jjjjj

T

jjjjjii

R

RRHPHKHPFH

δ

δ

{ } 1,1111

..

+++++ = jij

K

T

ji RE

FK

διι { } 01 =+iE ι

Innovation =

White Noise for

Kalman Filter Gain!!!

&

Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-57-320.jpg)

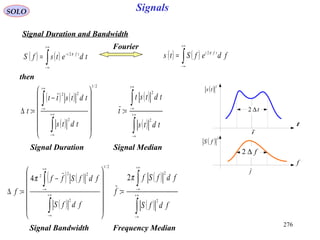

![61

1|1| ˆˆ: −− −=−= kkkkkkkk zzxHzi

Recursive Bayesian EstimationSOLO

Linear Gaussian Markov Systems (continue – 18)

Innovation

The innovation is the quantity:

We found that:

{ } ( ){ } { } 0ˆ||ˆ| 1|1:11:11|1:1 =−=−= −−−−− kkkkkkkkkk zZzEZzzEZiE

[ ][ ]{ } { } k

T

kkkkkk

T

kkk

T

kkkkkk SHPHRZiiEZzzzzE =+==−− −−−−− :ˆˆ 1|1:11:11|1|

Using the smoothing property of the expectation:

{ }{ } ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( ) { }xEdxxpxdxdyyxpx

dxdyypyxpxdyypdxyxpxyxEE

x

X

x y

YX

x y

yxp

YYX

y

Y

x

YX

YX

==

=

=

=

∫∫ ∫

∫ ∫∫ ∫

∞+

−∞=

∞+

−∞=

∞+

−∞=

∞+

−∞=

∞+

−∞=

∞+

−∞=

∞+

−∞=

,

||

,

,

||

,

{ } { }{ }1:1 −= k

T

jk

T

jk ZiiEEiiEwe have:

Assuming, without loss of generality, that k-1 ≥ j, and innovation I (j) is

Independent on Z1:k-1, and it can be taken outside the inner expectation:

{ } { }{ } { } 0

0

1:11:1 =

== −−

T

jkkk

T

jk

T

jk iZiEEZiiEEiiE

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-60-320.jpg)

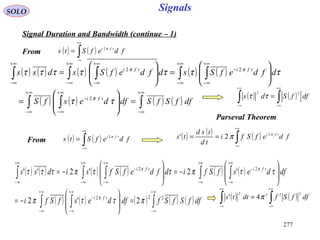

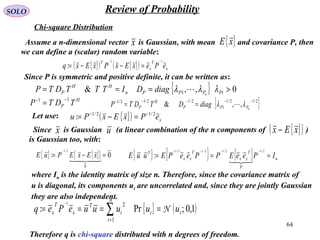

![68

SOLO Review of Probability

Derivation of Chi and Chi-square Distributions (continue – 3)

Tail probabilities of the chi-square and normal densities.

The Table presents the points on the chi-square

distribution for a given upper tail probability

{ }xyQ >= Pr

where y = χn

2

and n is the number of degrees

of freedom. This tabulated function is also

known as the complementary distribution.

An alternative way of writing the previous

equation is: { } ( )QxyQ n −=≤=− 1Pr1

2

χ

which indicates that at the left of the point x

the probability mass is 1 – Q. This is

100 (1 – Q) percentile point.

Examples

1. The 95 % probability region for χ2

2

variable

can be taken at the one-sided probability

region (cutting off the 5% upper tail): ( )[ ] [ ]99.5,095.0,0

2

2 =χ

.5 99

2. Or the two-sided probability region (cutting off both 2.5% tails): ( ) ( )[ ] [ ]38.7,05.0975.0,025.0

2

2

2

2 =χχ

.0 51

.0 975 .0 025.0 05

.7 38

3. For χ1002 variable, the two-sided 95% probability region (cutting off both 2.5% tails) is:

( ) ( )[ ] [ ]130,74975.0,025.0

2

100

2

100 =χχ

74

130](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-67-320.jpg)

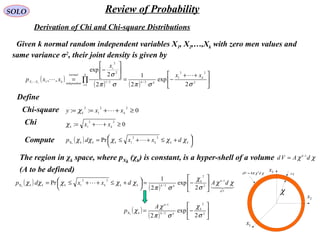

![69

SOLO Review of Probability

Derivation of Chi and Chi-square Distributions (continue – 4)

Note the skewedness of the chi-square

distribution: the above two-sided regions are

not symmetric about the corresponding means

{ } nE n =

2

χ

Tail probabilities of the chi-square and normal densities.

For degrees of freedom above 100, the

following approximation of the points on the

chi-square distribution can be used:

( ) ( )[ ]22

121

2

1

1 −+−=− nQQn Gχ

where G ( ) is given in the last line of the Table

and shows the point x on the standard (zero

mean and unity variance) Gaussian distribution

for the same tail probabilities.

In the case Pr { y } = N (y; 0,1) and with

Q = Pr { y>x }, we have x (1-Q) :=G (1-Q)

.5 99.0 51

.0 975 .0 025.0 05

.7 38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-68-320.jpg)

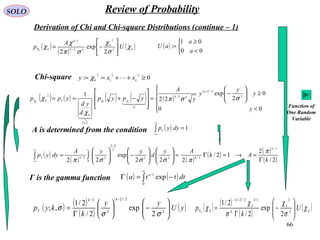

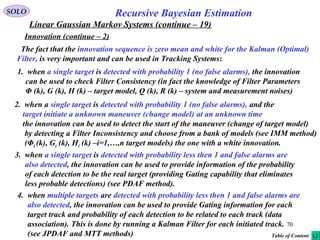

![71

Recursive Bayesian EstimationSOLO

Linear Gaussian Markov Systems (continue – 20)

Evaluation of Kalman Filter Consistency

A state-estimator (filter) is called consistent if its state estimation error satisfy

( ) ( ){ } ( ){ } 0|~:|ˆ ==− kkxEkkxkxE

( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( )[ ]{ } ( ) ( ){ } ( )kkPkkxkkxEkkxkxkkxkxE TT

||~|~:|ˆ|ˆ ==−−

this is a finite-sample consistency property, that is, the estimation errors based on a

finite number of samples (measurements) should be consistent with the theoretical

statistical properties:

• Have zero mean (i.e. the estimates are unbiased).

• Have covariance matrix as calculated by the Filter.

The Consistency Criteria of a Filter are:

1. The state errors should be acceptable as zero mean and have magnitude commensurate

with the state covariance as yielded by the Filter.

2. The innovation should have the same property as in (1).

3. The innovation should be white noise.

Only the last two criteria (based on innovation) can be tested in real data applications.

The first criterion, which is the most important, can be tested only in simulations.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-70-320.jpg)

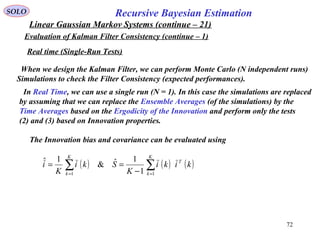

![73

Recursive Bayesian EstimationSOLO

Linear Gaussian Markov Systems (continue – 22)

Evaluation of Kalman Filter Consistency (continue – 2)

Real time (Single-Run Tests) (continue – 1)

Test 2: ( ) ( ){ } ( ){ } ( ) ( ){ } ( )kSkikiEkiEkkzkzE T

===−− &0:1|ˆ

Using the Time-Average Normalized Innovation

Squared (NIS) statistics

( ) ( ) ( )∑=

−

=

K

k

T

i kikSki

K 1

11

:ε

must have a chi-square distribution with

K nz degrees of freedom.

iK ε

Tail probabilities of the chi-square and normal densities.

The test is successful if [ ]21,rri ∈ε

where the confidence interval [r1,r2] is defined

using the chi-square distribution of iε

[ ]{ } αε −=∈ 1,Pr 21 rri

For example for K=50, nz=2, and α=0.05, using the two

tails of the chi-square distribution we get

( )

( )

==→=

==→=

→

6.250/130130925.0

5.150/7474025.0

~50

2

2

100

1

2

1002

100

r

r

i

χ

χ

χε

.0 975

.0 025

74

130](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-72-320.jpg)

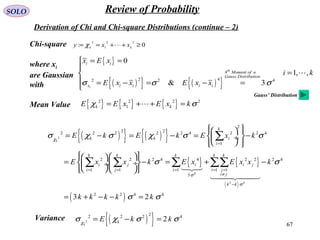

![74

Recursive Bayesian EstimationSOLO

Linear Gaussian Markov Systems (continue – 23)

Evaluation of Kalman Filter Consistency (continue – 3)

Real time (Single-Run Tests) (continue – 2)

Test 3: Whiteness of Innovation

Use the Normalized Time-Average Autocorrelation

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

2/1

111

:

−

===

+++= ∑∑∑

K

k

T

K

k

T

K

k

T

i lkilkikikilkikilρ

In view of the Central Limit Theorem, for large K, this statistics is normal distributed.

For l≠0 the variance can be shown to be 1/K that tends to zero for large K.

Denoting by ξ a zero-mean unity-variance normal

random variable, let r1 such that

[ ]{ } αξ −=−∈ 1,Pr 11 rr

For α=0.05, will define (from the normal distribution)

r1 = 1.96. Since has standard deviation of

The corresponding probability region for α=0.05 will

be [-r, r] where

iρ K/1

KKrr /96.1/1 ==

Normal Distribution](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-73-320.jpg)

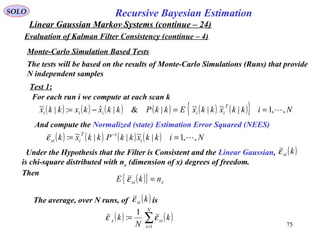

![76

Recursive Bayesian EstimationSOLO

Linear Gaussian Markov Systems (continue – 25)

Evaluation of Kalman Filter Consistency (continue – 5)

Monte-Carlo Simulation Based Tests (continue – 1)

Test 1 (continue – 1):

The average, over N runs, of is( )kxiε

( ) ( )∑=

=

N

i

xix k

N

k

1

1

: εε

The test is successful if [ ]21,rrx ∈ε

where the confidence interval [r1,r2] is defined

using the chi-square distribution of iε

[ ]{ } αε −=∈ 1,Pr 21 rrx

For example for N=50, nx=2, and α=0.05, using the two

tails of the chi-square distribution we get

( )

( )

==→=

==→=

→

6.250/130130925.0

5.150/7474025.0

~50

2

2

100

1

2

1002

100

r

r

i

χ

χ

χε

Tail probabilities of the chi-square and normal densities.

.0 975

.0 025

74

130

must have a chi-square distribution with

N nx degrees of freedom.

xN ε](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-75-320.jpg)

![77

Recursive Bayesian EstimationSOLO

Linear Gaussian Markov Systems (continue – 26)

Evaluation of Kalman Filter Consistency (continue – 6)

Monte-Carlo Simulation Based Tests (continue – 2)

The test is successful if [ ]21,rri ∈ε

where the confidence interval [r1,r2] is defined

using the chi-square distribution of iε

[ ]{ } αε −=∈ 1,Pr 21 rri

For example for N=50, nz=2, and α=0.05, using the two

tails of the chi-square distribution we get

( )

( )

==→=

==→=

→

6.250/130130925.0

5.150/7474025.0

~50

2

2

100

1

2

1002

100

r

r

i

χ

χ

χε

Tail probabilities of the chi-square and normal densities.

.0 975

.0 025

74

130

must have a chi-square distribution with

N nz degrees of freedom.

iN ε

Test 2: ( ) ( ){ } ( ){ } ( ) ( ){ } ( )kSkikiEkiEkkzkzE T

===−− &0:1|ˆ

Using the Normalized Innovation Squared (NIS)

statistics, compute from N Monte-Carlo runs:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∑=

−

=

N

j

jj

T

ji kikSki

N

k

1

11

:ε](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-76-320.jpg)

![78

Recursive Bayesian EstimationSOLO

Linear Gaussian Markov Systems (continue – 27)

Evaluation of Kalman Filter Consistency (continue – 7)

Test 3: Whiteness of Innovation

Use the Normalized Sample Average Autocorrelation

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

2/1

111

:,

−

===

= ∑∑∑

N

j

j

T

j

N

j

j

T

j

N

j

j

T

ji mimikikimikimkρ

In view of the Central Limit Theorem, for large N, this statistics is normal distributed.

For k≠m the variance can be shown to be 1/N that tends to zero for large N.

Denoting by ξ a zero-mean unity-variance normal

random variable, let r1 such that

[ ]{ } αξ −=−∈ 1,Pr 11 rr

For α=0.05, will define (from the normal distribution)

r1 = 1.96. Since has standard deviation of

The corresponding probability region for α=0.05 will

be [-r, r] where

iρ N/1

NNrr /96.1/1 ==

Normal Distribution

Monte-Carlo Simulation Based Tests (continue – 3)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-77-320.jpg)

![79

Recursive Bayesian EstimationSOLO

Linear Gaussian Markov Systems (continue – 28)

Evaluation of Kalman Filter Consistency (continue – 8)

Examples Bar-Shalom, Y, Li, X-R, “Estimation and Tracking: Principles, Techniques

and Software”, Artech House, 1993, pg.242

Monte-Carlo Simulation Based Tests (continue – 4)

Single Run, 95% probability

[ ]99.5,0∈xεTest (a) Passes if

A one-sided region is considered.

For nx = 2 we have

( ) ( )[ ] [ ]99.5,095.0,02 2

2

2

2 == χχxn

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∑=

−

=

K

k

T

x kkxkkPkkx

K

k

1

1

|~||~1

:ε

( ) ( ) ( ) qkxkkx +−Φ= 1

See behavior of for various values of the process noise q

for filters that are perfectly matched.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-78-320.jpg)

![80

Recursive Bayesian EstimationSOLO

Linear Gaussian Markov Systems (continue – 29)

Evaluation of Kalman Filter Consistency (continue – 9)

Examples Bar-Shalom, Y, Li, X-R, “Estimation and Tracking: Principles, Techniques

and Software”, Artech House, 1993, pg.244

Monte-Carlo Simulation Based Tests (continue – 5)

Monte-Carlo, N=50, 95% probability

[ ] [ ]6.2,5.150/130,50/74 =∈xεTest (a) Passes if

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∑=

−

=

N

j

jj

T

jx kkxkkPkkx

N

k

1

1

|~||~1

:ε(a)

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

2/1

111

:,

−

===

= ∑∑∑

N

j

j

T

j

N

j

j

T

j

N

j

j

T

ji mimikikimikimkρ(c)

The corresponding probability region for

α=0.05 will be [-r, r] where

28.050/96.1/1 === Nrr

[ ] [ ]43.1,65.050/4.71,50/3.32 =∈iεTest (b) Passes if

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∑=

−

=

N

j

jj

T

ji kikSki

N

k

1

11

:ε(b)

( ) ( )[ ] [ ]130,74925.0,025.02 2

100

2

100 == χχxn

( ) ( )[ ] [ ]71,32925.0,025.01 2

100

2

100 == χχzn](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-79-320.jpg)

![81

Recursive Bayesian EstimationSOLO

Linear Gaussian Markov Systems (continue – 30)

Evaluation of Kalman Filter Consistency (continue – 10)

Examples Bar-Shalom, Y, Li, X-R, “Estimation and Tracking: Principles, Techniques

and Software”, Artech House, 1993, pg.245

Monte-Carlo Simulation Based Tests (continue – 6)

Example Mismatched Filter

A Mismatched Filter is tested: Real System Process Noise q = 9 Filter Model Process Noise qF=1

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∑=

−

=

K

k

T

x kkxkkPkkx

K

k

1

1

|~||~1

:ε

( ) ( ) ( ) qkxkkx +−Φ= 1

(1) Single Run

(2) A N=50 runs Monte-Carlo with the

95% probability region

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∑=

−

=

N

j

jj

T

jx kkxkkPkkx

N

k

1

1

|~||~1

:ε

[ ] [ ]6.2,5.150/130,50/74 =∈xεTest (2) Passes if

( ) ( )[ ] [ ]130,74925.0,025.02 2

100

2

100 == χχxn

Test Fails

Test Fails

[ ]99.5,0∈xεTest (1) Passes if

( ) ( )[ ] [ ]99.5,095.0,02 2

2

2

2 == χχxn](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-80-320.jpg)

![82

Recursive Bayesian EstimationSOLO

Linear Gaussian Markov Systems (continue – 31)

Evaluation of Kalman Filter Consistency (continue – 11)

Examples Bar-Shalom, Y, Li, X-R, “Estimation and Tracking: Principles, Techniques

and Software”, Artech House, 1993, pg.246

Monte-Carlo Simulation Based Tests (continue – 7)

Example Mismatched Filter (continue -1)

A Mismatched Filter is tested: Real System Process Noise q = 9 Filter Model Process Noise qF=1

( ) ( ) ( ) qkxkkx +−Φ= 1

(3) A N=50 runs Monte-Carlo with the

95% probability region

(4) A N=50 runs Monte-Carlo with the

95% probability region

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∑=

−

=

N

j

jj

T

ji kikSki

N

k

1

11

:ε

[ ] [ ]43.1,65.050/4.71,50/3.32 =∈iεTest (3) Passes if

( ) ( )[ ] [ ]71,32925.0,025.01 2

100

2

100 == χχzn

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

2/1

111

:,

−

===

= ∑∑∑

N

j

j

T

j

N

j

j

T

j

N

j

j

T

ji mimikikimikimkρ

(c)

The corresponding probability region for

α=0.05 will be [-r, r] where

28.050/96.1/1 === Nrr

Test Fails

Test Fails](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-81-320.jpg)

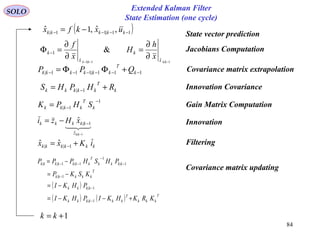

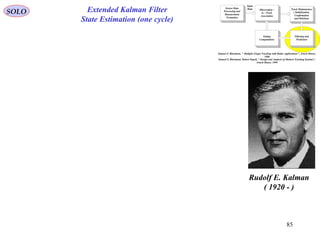

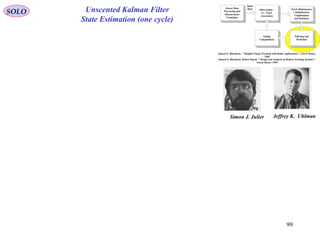

![83

Extended Kalman Filter

Sensor Data

Processing and

Measurement

Formation

Observation -

to - Track

Association

Input

Data Track Maintenance

( Initialization,

Confirmation

and Deletion)

Filtering and

Prediction

Gating

Computations

Samuel S. Blackman, " Multiple-Target Tracking with Radar Applications", Artech House,

1986

Samuel S. Blackman, Robert Popoli, " Design and Analysis of Modern Tracking Systems",

Artech House, 1999

SOLO

In the extended Kalman filter, (EKF) the state

transition and observation models need not be linear

functions of the state but may instead be (differentiable)

functions.

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )kwkukxkfkx +=+ ,,1

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )11,1,11 +++++=+ kkukxkhkz ν

State vector dynamics

Measurements

( ) ( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( ){ } ( )kPkekeEkxEkxke x

T

xxx =−= &:

( ) ( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( ){ } ( ) lk

T

www kQlekeEkwEkwke ,

0

&: δ=−=

( ) ( ){ } lklekeE

T

vw ,0 ∀=

=

≠

=

lk

lk

lk

1

0

,δ

The function f can be used to compute the predicted state from the previous estimate

and similarly the function h can be used to compute the predicted measurement from

the predicted state. However, f and h cannot be applied to the covariance directly.

Instead a matrix of partial derivatives (the Jacobian) is computed.

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ){ } ( )[ ] ( )

( ){ }

( ) ( )

( ){ }

( ) ( )keke

x

f

keke

x

f

kekukxEkfkukxkfke wx

Hessian

kxE

T

xx

Jacobian

kxE

wx ++

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

=+−=+

2

2

2

1

,,,,1

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ){ } ( )[ ] ( )

( ){ }

( ) ( )

( ){ }

( ) ( 111

2

1

111,1,11,1,11

1

2

2

1

++++

∂

∂

+++

∂

∂

=+++++−+++=+

++

kke

x

h

keke

x

h

kkukxEkhkukxkhke x

Hessian

kxE

T

xx

Jacobian

kxE

z νν

Taylor’s Expansion:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-82-320.jpg)

![87

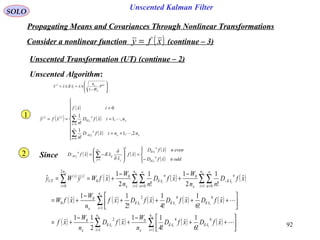

Uscented Kalman FilterSOLO

When the state transition and observation models – that is, the predict and update

functions f and h (see above) – are highly non-linear, the extended Kalman filter can

give particularly poor performance [JU97]. This is because only the mean is

propagated through the non-linearity. The unscented Kalman filter (UKF) [JU97]

uses a deterministic sampling technique known as the to pick a minimal set of

sample points (called sigma points) around the mean. These sigma points are then

propagated through the non-linear functions and the covariance of the estimate is

then recovered. The result is a filter which more accurately captures the true mean

and covariance. (This can be verified using Monte Carlo sampling or through a

Taylor series expansion of the posterior statistics.) In addition, this technique

removes the requirement to analytically calculate Jacobians, which for complex

functions can be a difficult task in itself.

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )kwkukxkfkx +=+ ,,1

( ) ( )[ ] ( )11,11 ++++=+ kkxkhkz ν

State vector dynamics

Measurements

( ) ( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( ){ } ( )kPkekeEkxEkxke x

T

xxx =−= &:

( ) ( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( ){ } ( ) lk

T

www kQlekeEkwEkwke ,

0

&: δ=−=

( ) ( ){ } lklekeE

T

vw ,0 ∀=

=

≠

=

lk

lk

lk

1

0

,δ

The Unscent Algorithm using ( ) ( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( ){ } ( )kPkekeEkxEkxke x

T

xxx =−= &:

Determines ( ) ( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( ){ } ( )kPkekeEkzEkzke z

T

zzz =−= &:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-86-320.jpg)

![88

Unscented Kalman FilterSOLO

( ) ( )[ ]

( )

n

n

j j

j

n

x

n

x

n

x

x

x

xx

fx

n

xxf

∂

∂

=∇⋅

∇⋅=+

∑

∑

=

∞

=

1

0

ˆ

:

!

1

ˆ

δδ

δδ

Develop the nonlinear function f in a Taylor series

around

xˆ

Define also the operator ( )[ ] ( )xf

x

xfxfD

n

n

j j

jx

n

x

n

x

x

∂

∂

=∇⋅= ∑=1

: δδδ

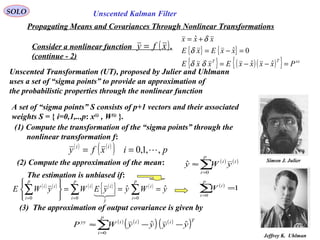

Propagating Means and Covariances Through Nonlinear Transformations

Consider a nonlinear function .( )xfy =

Let compute

Assume is a random variable with a probability density function pX (x) (known or

unknown) with mean and covariance

x

{ } ( ) ( ){ }Txx

xxxxEPxEx ˆˆ,ˆ −−==

( ){ } { }

( )[ ]{ } ∑ ∑∑

∑

∞

= =

∞

=

∞

=

∂

∂

=∇⋅=

=+=

0

ˆ

10

ˆ

0

!

1

!

1

!

1

ˆˆ

n

x

n

n

j j

j

n

x

n

x

n

n

x

f

x

xE

n

fxE

n

DE

n

xxfEy

x

δδ

δ δ

{ } { }

{ } ( )( ){ } xxTT

PxxxxExxE

xxExE

xxx

=−−=

=−=

+=

ˆˆ

0ˆ

ˆ

δδ

δ

δ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-87-320.jpg)

![89

Unscented Kalman Filter

SOLO

Propagating Means and Covariances Through Nonlinear Transformations

Consider a nonlinear function .

(continue – 1)

( )xfy =

{ } { }

{ } ( )( ){ } xxTT

PxxxxExxE

xxExE

xxx

=−−=

=−=

+=

ˆˆ

0ˆ

ˆ

δδ

δ

δ

( ){ } ( )

+

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

+

∂

∂

+=

∂

∂

=+=

∑∑∑

∑∑ ∑

===

=

∞

= =

x

n

j j

jx

n

j j

jx

n

j j

j

x

n

j j

j

n

x

n

n

j j

j

f

x

xEf

x

xEf

x

xE

f

x

xExff

x

xE

n

xxfEy

xxx

xx

ˆ

4

1

ˆ

3

1

ˆ

2

1

ˆ

10

ˆ

1

!4

1

!3

1

!2

1

ˆ

!

1

ˆˆ

δδδ

δδδ

Since all the differentials of f are computed around the mean (non-random)xˆ

( )[ ]{ } ( )[ ]{ } { }( )[ ] ( )[ ]xx

xxT

xxx

TT

xxx

TT

xxx fPfxxEfxxEfxE ˆˆˆˆ

2

∇∇=∇∇=∇∇=∇⋅ δδδδδ

( )[ ]{ } { } { } 0

ˆ

1

0ˆ

1

ˆ0

ˆ =

∂

∂

=

∂

∂

=

∇⋅=∇⋅ ∑∑ ==

x

n

j j

j

x

n

j j

j

x

xxx f

x

xEf

x

xEfxEfxE

xx

δδδδ

( ){ } [ ]{ } ( ) ( )[ ] [ ]{ } [ ]{ } +++∇∇+==+= ∑

∞

=

xxxxxx

xxT

x

n

x

n

x fDEfDEfPxffDE

n

xxfEy ˆ

4

ˆ

3

ˆ

0

ˆ

!4

1

!3

1

!2

1

ˆ

!

1

ˆˆ δδδδ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-88-320.jpg)

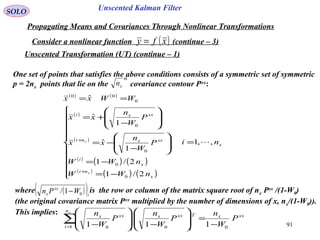

![93

Unscented Kalman Filter

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )∑=

++

−

+∇∇+=

x

ii

n

i

xx

x

xxT

UT xfDxfD

n

W

xfPxfy

1

640

ˆ

!6

1

ˆ

!4

11

ˆ

2

1

ˆˆ δδ

( )

i

xxx

i

i

P

W

n

xxxx

−

±=±=

01

ˆˆ δ

SOLO

Propagating Means and Covariances Through Nonlinear Transformations

Consider a nonlinear function (continue – 4)( )xfy =

Unscented Transformation (UT) (continue – 3)

Unscented Algorithm:

( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( )xfPxfP

W

n

n

W

xfP

W

n

P

W

n

n

W

xfP

W

n

P

W

n

n

W

xfD

n

W

xxTxxxT

x

n

i

T

i

xxx

i

xxxT

x

n

i

T

i

xxx

i

xxxT

x

n

i

x

x

x

xx

i

ˆ

2

1

ˆ

12

11

ˆ

112

11

ˆ

112

11

ˆ

2

11

0

0

1 00

0

1 00

0

1

20

∇∇=∇

−

∇

−

=∇

−

−

∇

−

=

∇

−

−

∇

−

=

−

∑

∑∑

=

==

δ

Finally:

We found

( ){ } [ ]{ } ( ) ( )[ ] [ ]{ } [ ]{ } +++∇∇+==+= ∑

∞

=

xxxxxx

xxT

x

n

x

n

x fDEfDEfPxffDE

n

xxfEy ˆ

4

ˆ

3

ˆ

0

ˆ

!4

1

!3

1

!2

1

ˆ

!

1

ˆˆ δδδδ

We can see that the two expressions agree exactly to the third order.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-92-320.jpg)

![94

Unscented Kalman Filter

SOLO

Propagating Means and Covariances Through Nonlinear Transformations

Consider a nonlinear function (continue – 5)( )xfy =

Unscented Transformation (UT) (continue – 4)

Accuracy of the Covariance:

( ) ( ){ } { }

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( )[ ] [ ]{ } [ ]{ }

( ) ( )[ ] [ ]{ } [ ]{ }

T

xxxxxx

xxT

x

xxxxxx

xxT

x

T

m

m

xx

n

n

xx

TTTyy

fDEfDEfPxf

fDEfDEfPxf

fD

m

xfDxffD

n

xfDxfE

yyyyEyyyyEP

+++∇∇+⋅

⋅

+++∇∇+−

++

++=

−=−−=

∑∑

∞

=

∞

=

ˆ

4

ˆ

3

ˆ

ˆ

4

ˆ

3

ˆ

22

!4

1

!3

1

!2

1

ˆ

!4

1

!3

1

!2

1

ˆ

!

1

ˆˆ

!

1

ˆˆ

ˆˆˆˆ

δδ

δδ

δδδδ

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( ) ( )

( )

+

++

++=

∑∑

∑∑

∞

=

∞

=

∞

=

∞

=

T

m

m

x

n

n

x

T

n

n

x

T

x

T

n

n

x

T

x

T

fD

m

fD

n

E

xfxfD

n

ExfxfDExfD

n

ExfxfDExfxfxf

22

2

0

2

0

!

1

!

1

ˆˆ

!

1

ˆˆˆ

!

1

ˆˆˆˆˆ

δδ

δδδδ

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-93-320.jpg)

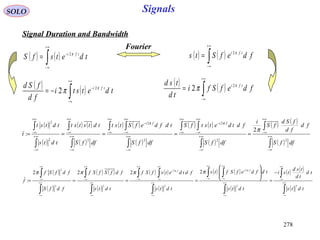

![96

Uscented Kalman FilterSOLO

( ) ( )∑∑ −−==

N

T

iiiz

N

ii zzPz

2

0

2

0

ψψβψβ

x

xPα

xP

zP

( )f

iβ

iβ

iψ

z

{ } [ ]xxi PxPxx ααχ −+=

Weighted

sample mean

Weighted

sample

covariance

Table of Content](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-95-320.jpg)

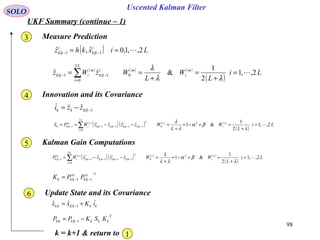

![97

Uscented Kalman Filter

SOLO

UKF Summary

Initialization of UKF

{ } ( ) ( ){ }T

xxxxEPxEx 00000|000

ˆˆˆ −−==

{ } [ ] ( )( ){ }

=−−===

R

Q

P

xxxxEPxxEx

TaaaaaTTaa

00

00

00

ˆˆ00ˆˆ

0|0

00000|0000

[ ]TTTTa

vwxx =:

For { }∞∈ ,,1 k

Calculate the Sigma Points ( )

( )

λγ

γ

γ +=

=−=

=+=

=

−−−−

+

−−

−−−−−−

−−−−

L

LiPxx

LiPxx

xx

i

kkkk

Li

kk

i

kkkk

i

kk

kkkk

,,1ˆˆ

,,1ˆˆ

ˆˆ

1|11|11|1

1|11|11|1

1|1

0

1|1

State Prediction and its Covariance

System Definition

( ) { } { }

( ) { } { }

==+=

==+−= −−−−−−−

lkk

T

lkkkkk

lkk

T

lkkkkkk

RvvEvEvxkhz

QwwEwEwuxkfx

,

,1111111

&0,

&0,,1

δ

δ

( ) Liuxkfx k

i

kk

i

kk 2,,1,0,ˆ,1ˆ 11|11| =−= −−−−

( ) ( ) ( )

( )

Li

L

W

L

WxWx m

i

m

L

i

i

kk

m

ikk 2,,1

2

1

&ˆˆ 0

2

0

1|1| =

+

=

+

== ∑=

−−

λλ

λ

0

1

2

( )

( )( ) ( ) ( )

( )

Li

L

W

L

WxxxxWP c

i

c

L

i

T

kk

i

kkkk

i

kk

c

ikk 2,,1

2

1

&1ˆˆˆˆ 2

0

2

0

1|1|1|1|1| =

+

=+−+

+

=−−= ∑=

−−−−−

λ

βα

λ

λ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-96-320.jpg)

![100

Estimators

( ) ( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( ){ } ( )kPkekeEkxEkxke x

T

xxx =−= &:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )kkvkkv

kvkxkHkz

kwkkukGkxkkx

ξ+Ψ=+

+=

Γ++Φ=+

1

1

SOLO

Kalman Filter Discrete Case & Colored Measurement Noise

Assume a discrete dynamic system

( ) ( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( ){ } ( ) lk

T

www kQlekeEkwEkwke ,

0

&: δ=−=

( ) ( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( ){ } ( ) lk

T

kRlekeEkvEkvke ,

0

&: δξξξ =−=

( ) ( ){ } { }0=lekeE

T

w ξ

=

≠

=

lk

lk

lk

1

0

,δ

Solution

Define a new “pseudo-measurement”:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]kvkxkHkkvkxkHkzkkzk +Ψ−++++=Ψ−+= 1111:ζ

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( ) ( ) ( )

( )

( ) ( ) ( )kxkHkkvkkvkwkkukGkxkkH

k

Ψ−Ψ−++Γ++Φ+=

ξ

11

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

( )

kkH

kkwkkHkukGkHkxkHkkkH

ε

ξ+Γ++++Ψ−Φ+= 111

*

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )kkukGkHkxkHk εζ +++= 1*](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-estimators-150110062422-conversion-gate02/85/2-estimators-99-320.jpg)

![101

Estimators

( ) ( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( ){ } ( )kPkekeEkxEkxke x

T

xxx =−= &:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )111211*1

1

++++++++=+

Γ++Φ=+

kkukGkHkxkHk

kwkkukGkxkkx

εζ

SOLO

Kalman Filter Discrete Case & Colored Measurement Noise

The new discrete dynamic system:

( ) ( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( ){ } ( ) lk

T

www kQlekeEkwEkwke ,

0

&: δ=−=

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ){ } ( ){ }

( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) lklk

TTT

kRlHlkQkkHlekeE

kEkwEkkHkke

,,11&

1:

δδ

ξε

εε

ε

++ΓΓ+=

+Γ+−=

( ) ( ){ } { }0=lekeE

T

w ξ

=

≠

=

lk

lk

lk

1

0

,δ

Solution (continue – 1)

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )kkwkkHk ξε +Γ+= 1:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )kHkkkHkH Ψ−Φ+= 1:*

( ) ( ){ } ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]{ } ( ) ( ) lk

TTTTTTT

kHkkQllHllwkwElkwE ,11 δξε +Γ=++Γ=

To decorrelate measurements and system noises write the discrete dynamic system:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

0

1*

1

kkukGkHkxkHkkD

kwkkukGkxkkx

εζ ++−−+