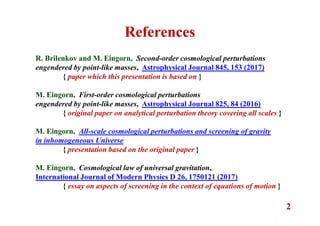

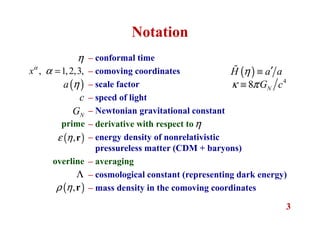

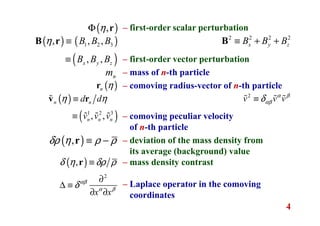

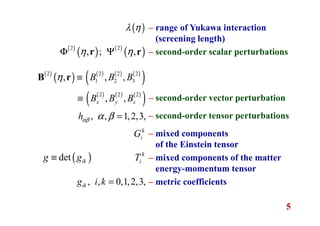

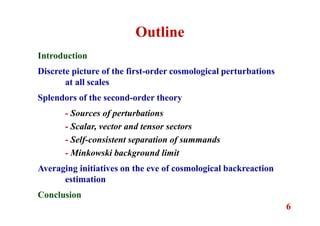

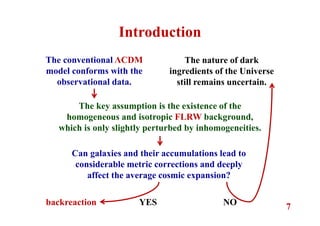

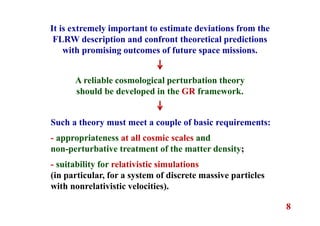

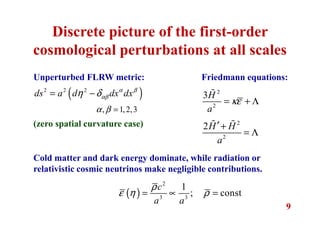

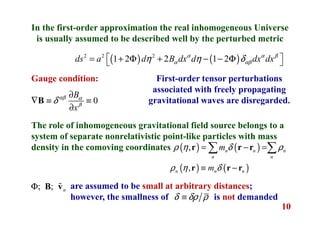

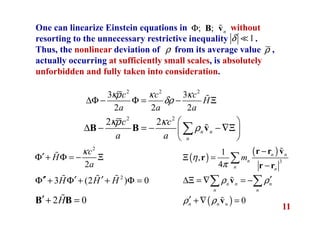

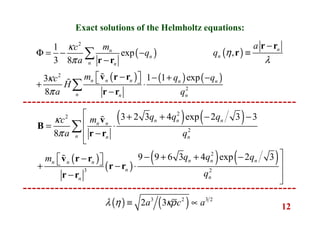

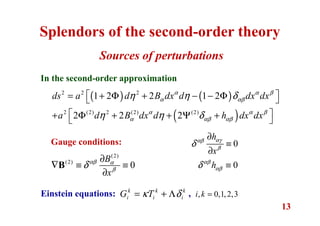

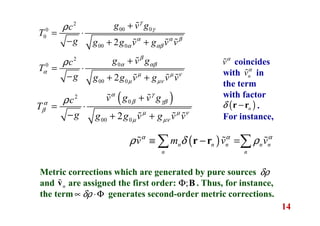

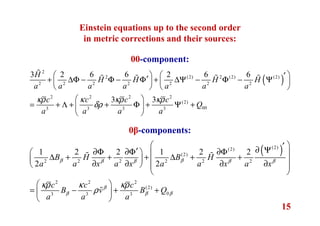

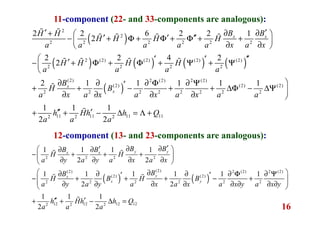

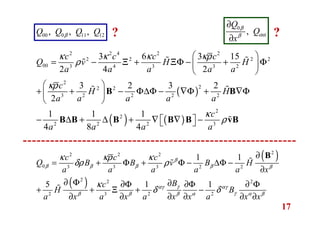

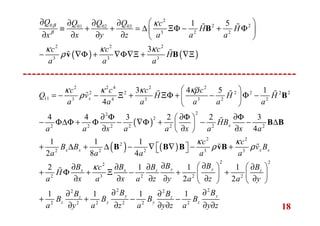

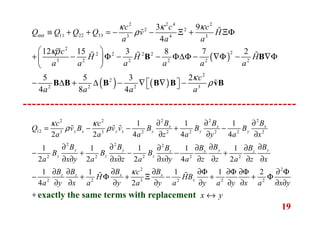

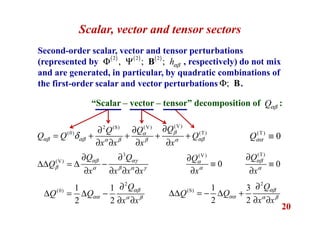

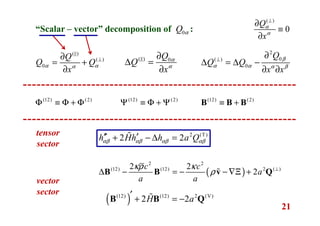

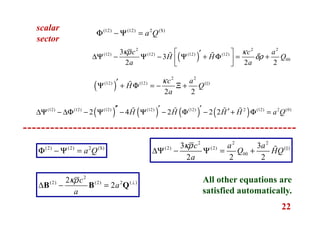

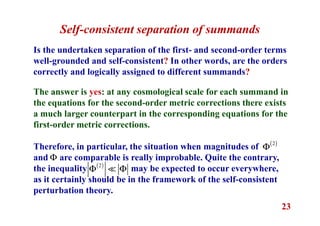

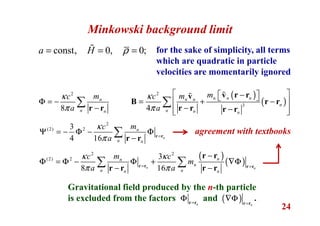

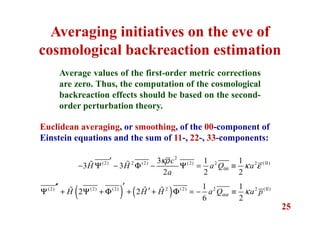

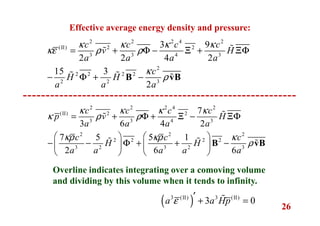

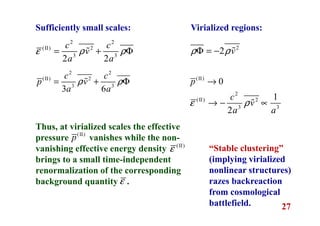

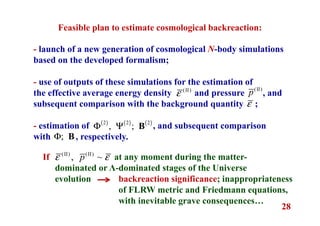

The document discusses second-order cosmological perturbations caused by point-like masses, building upon earlier works by Brilenkov and Eingorn. It highlights the need for a reliable cosmological perturbation theory within general relativity that accommodates all scales and does not impose limitations on mass density treatment. The study aims to understand the impact of inhomogeneous gravitational fields on cosmic expansion and metric corrections.