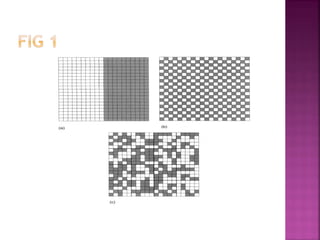

This document discusses the importance and process of mixing in pharmaceutical manufacturing. It makes several key points:

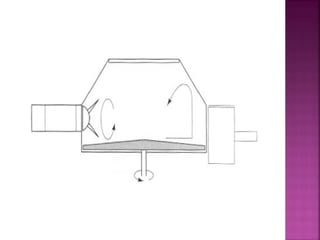

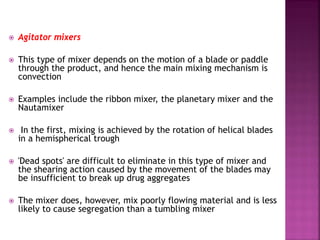

1) Mixing is required in most pharmaceutical products to ensure uniform distribution of active ingredients and proper functioning of the dosage form.

2) The type of mixing needed (positive, negative, neutral) depends on the product components and how they interact.

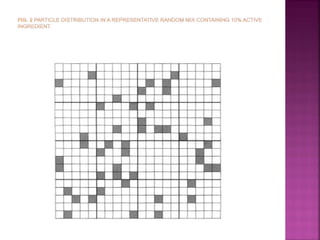

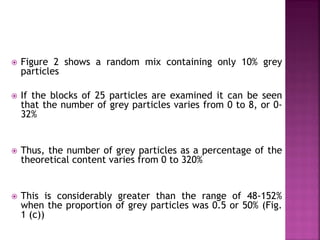

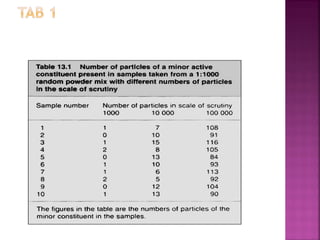

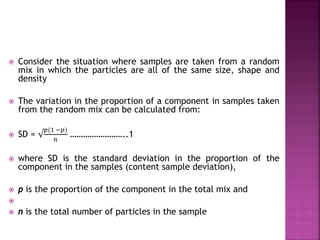

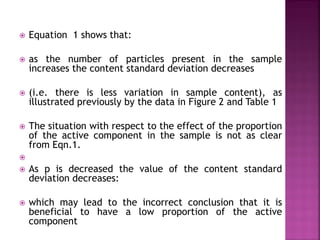

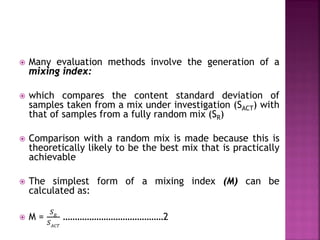

3) Achieving a perfectly mixed state is impossible, so the goal is a random mixture with minimal variation between doses.

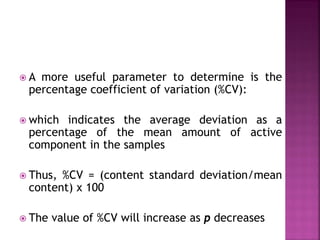

4) Both the number of particles in a dose and the proportion of active ingredient impact mixing quality and uniformity. More of each improves consistency.

![ Define the following terms:

[Mixing, separation, difusion, etc]

Respond to the following questions:

Give a detailed account of ………………

Explain in details the process of …………..

Describe in details with examples the…………

With examples, illustrate the pharmaceutical applications of ……………](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/15-mixing-200630110108/85/15-mixing-110-320.jpg)