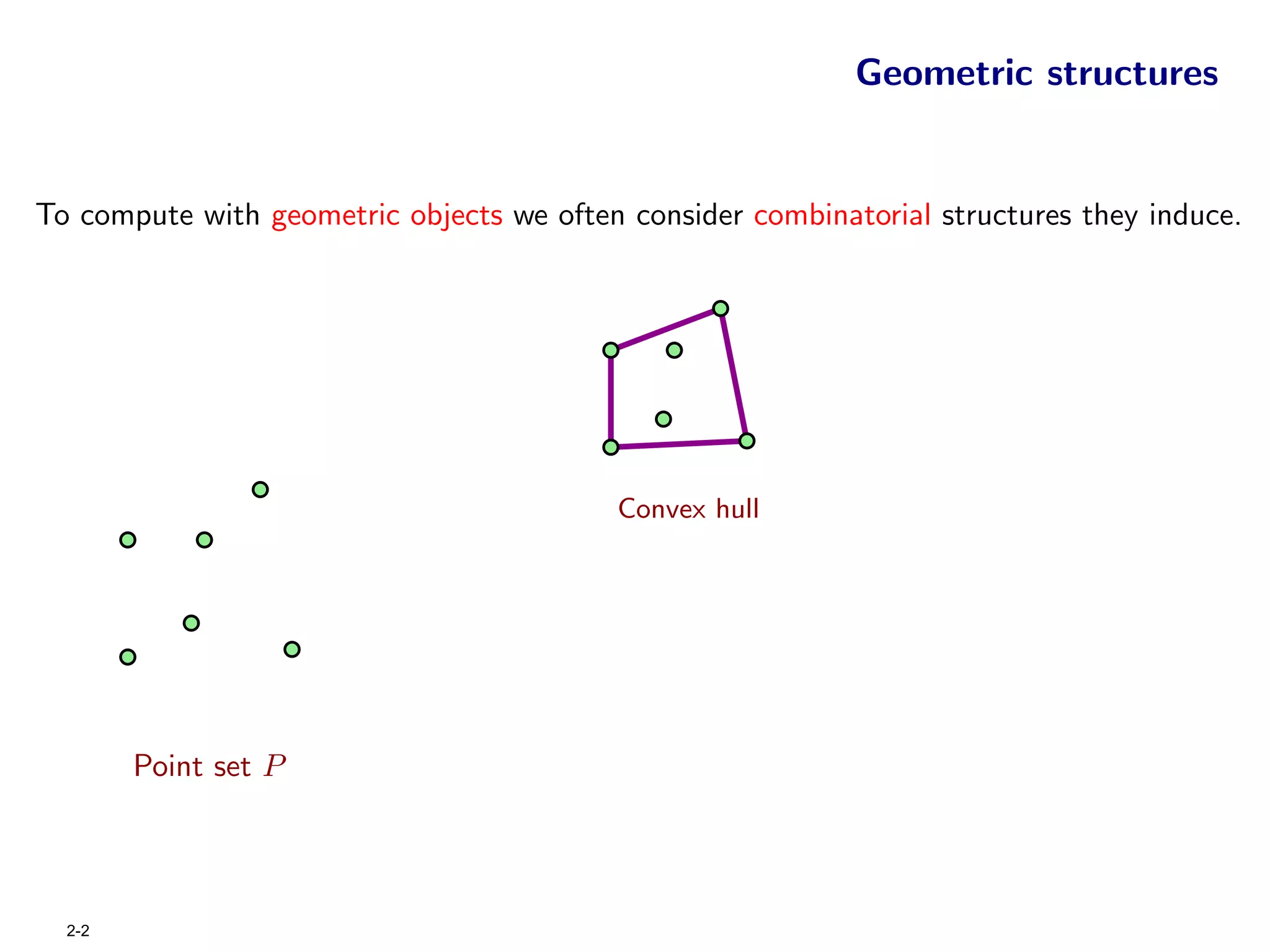

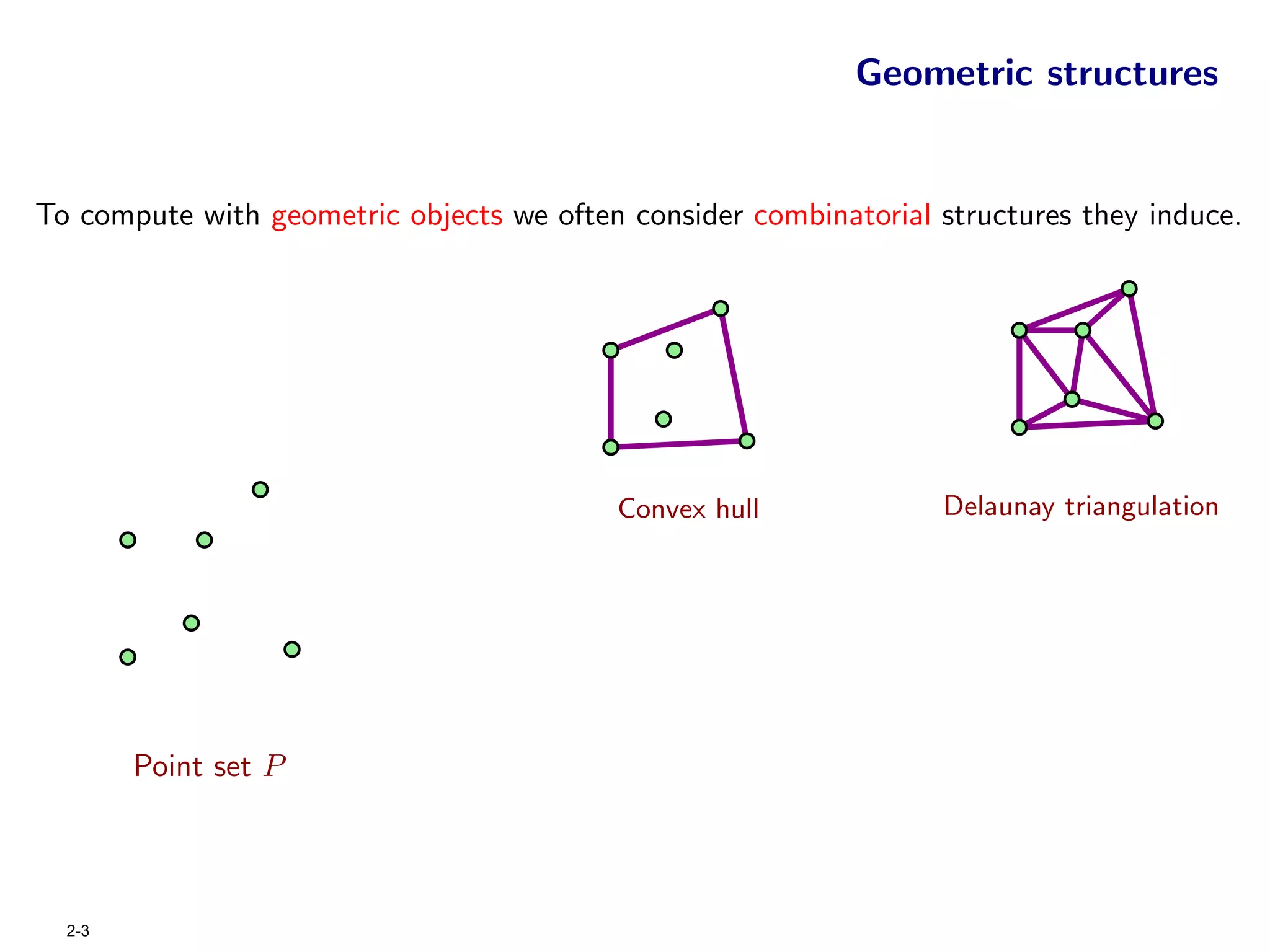

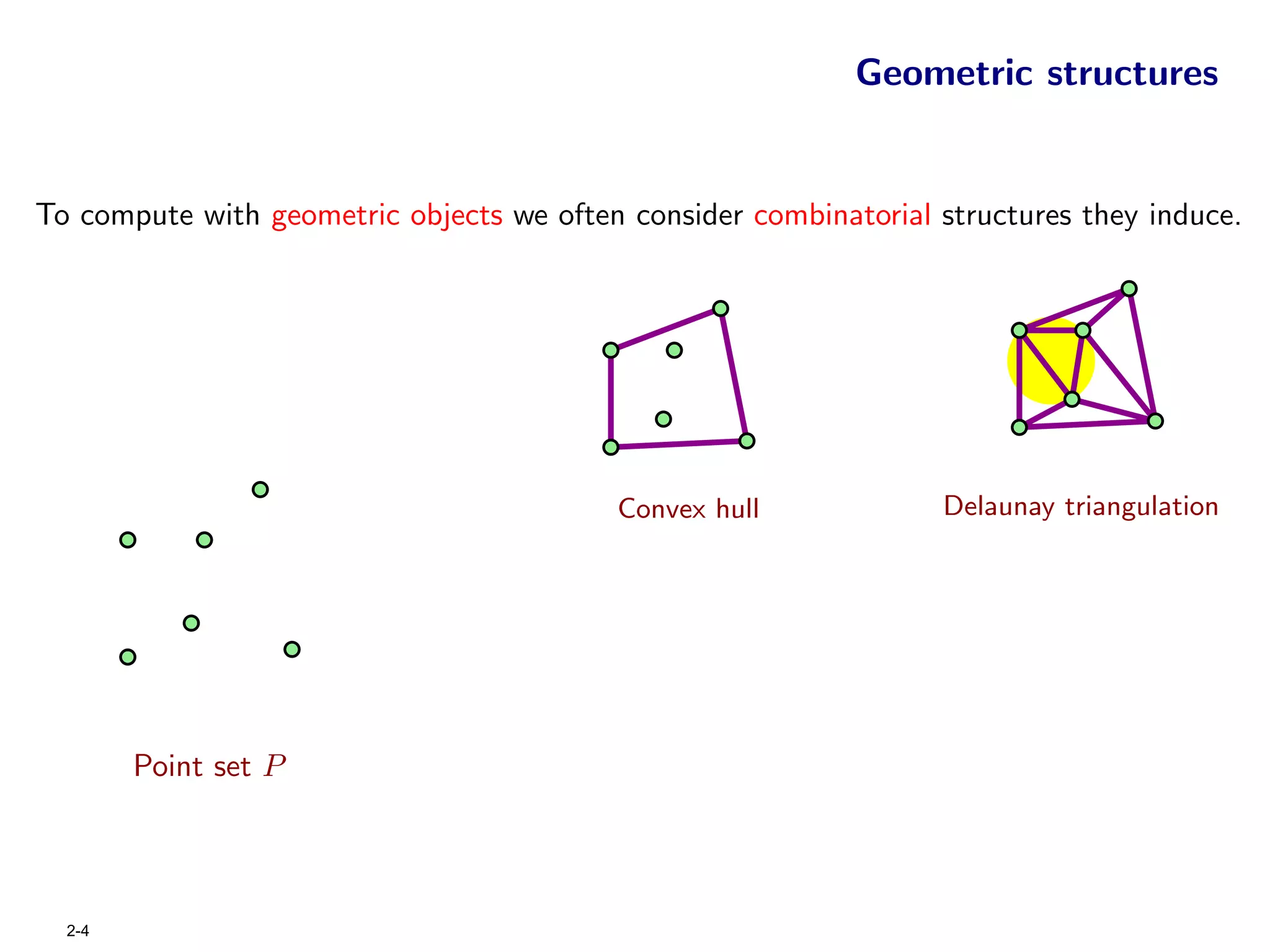

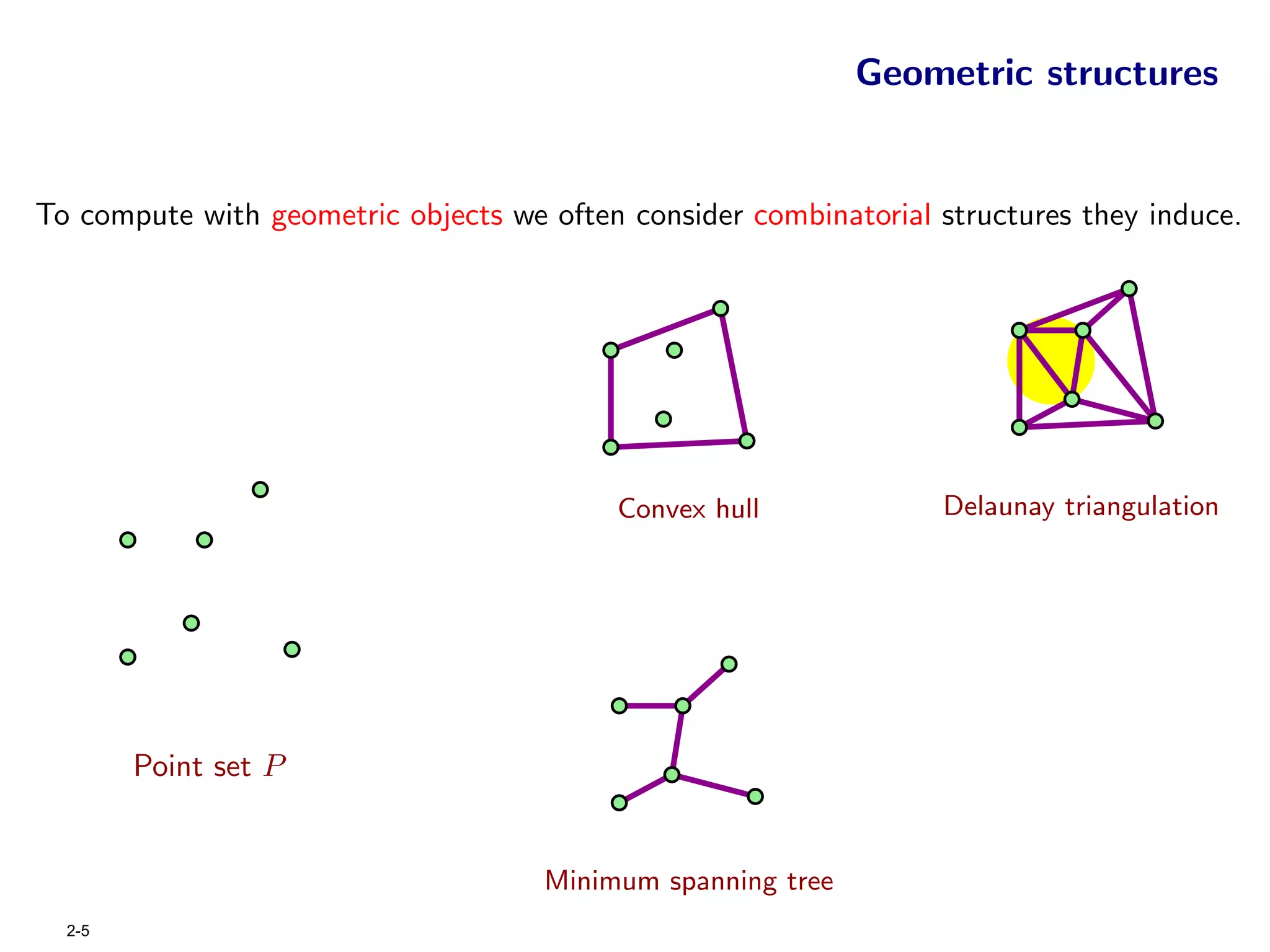

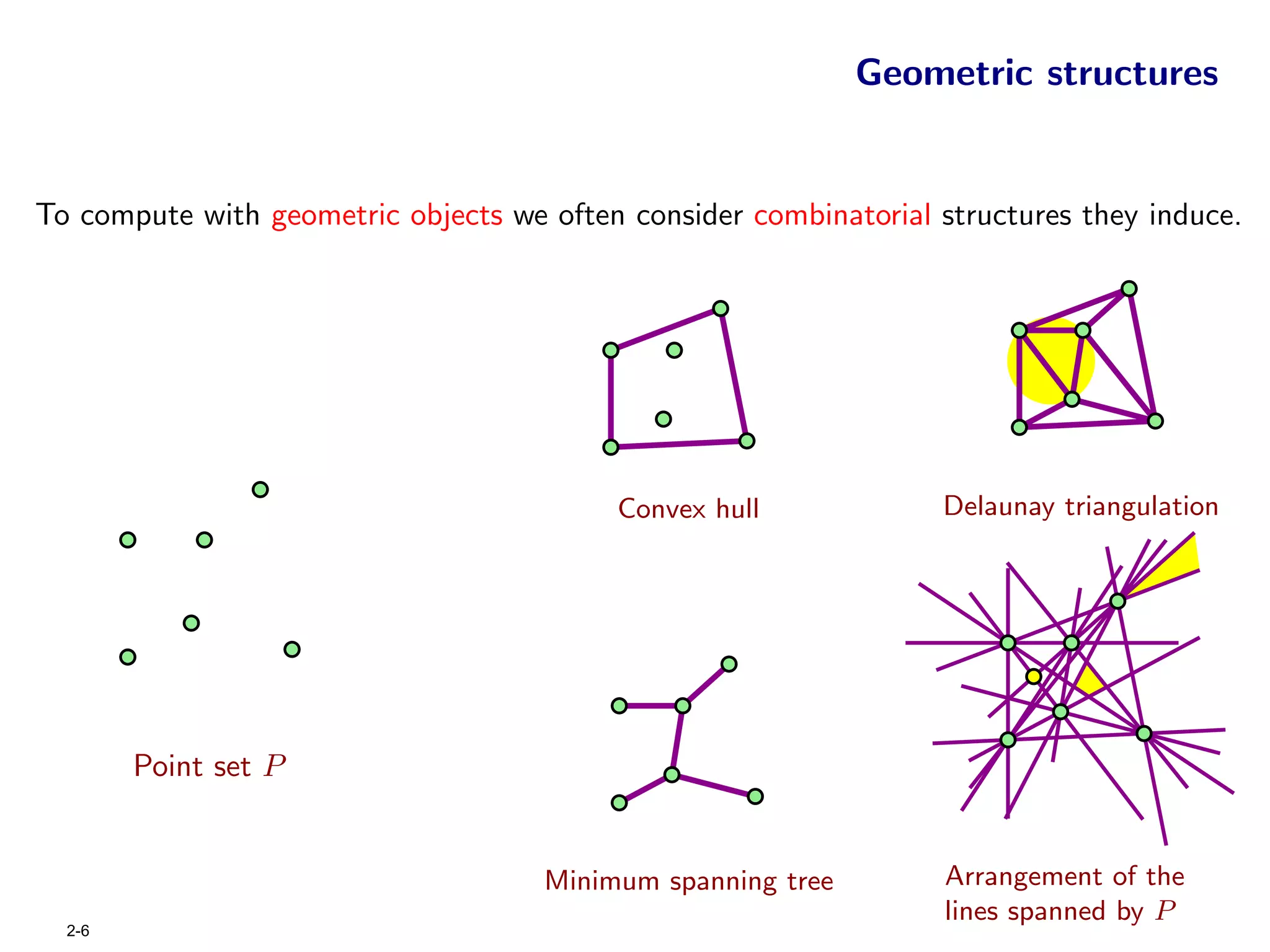

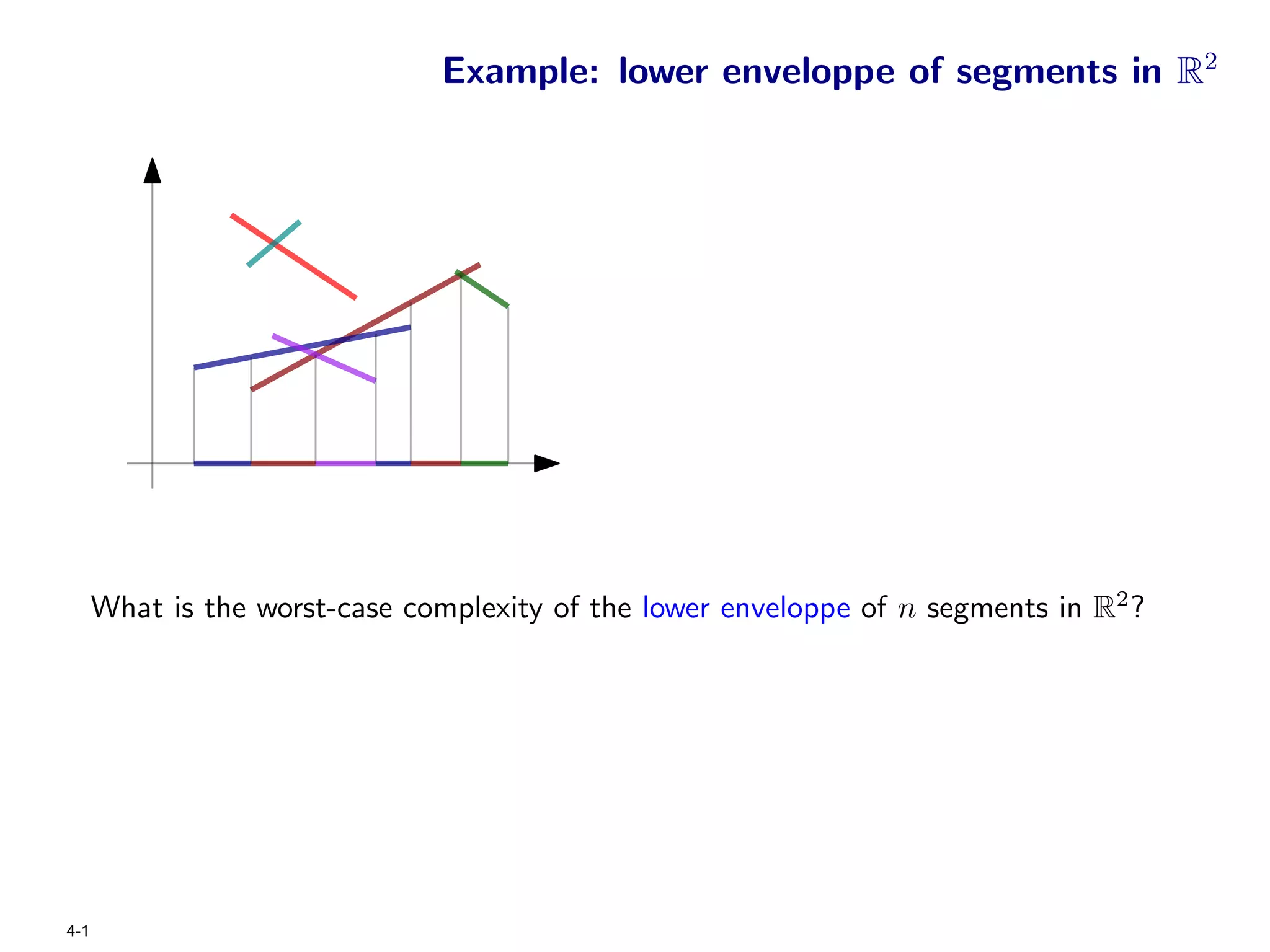

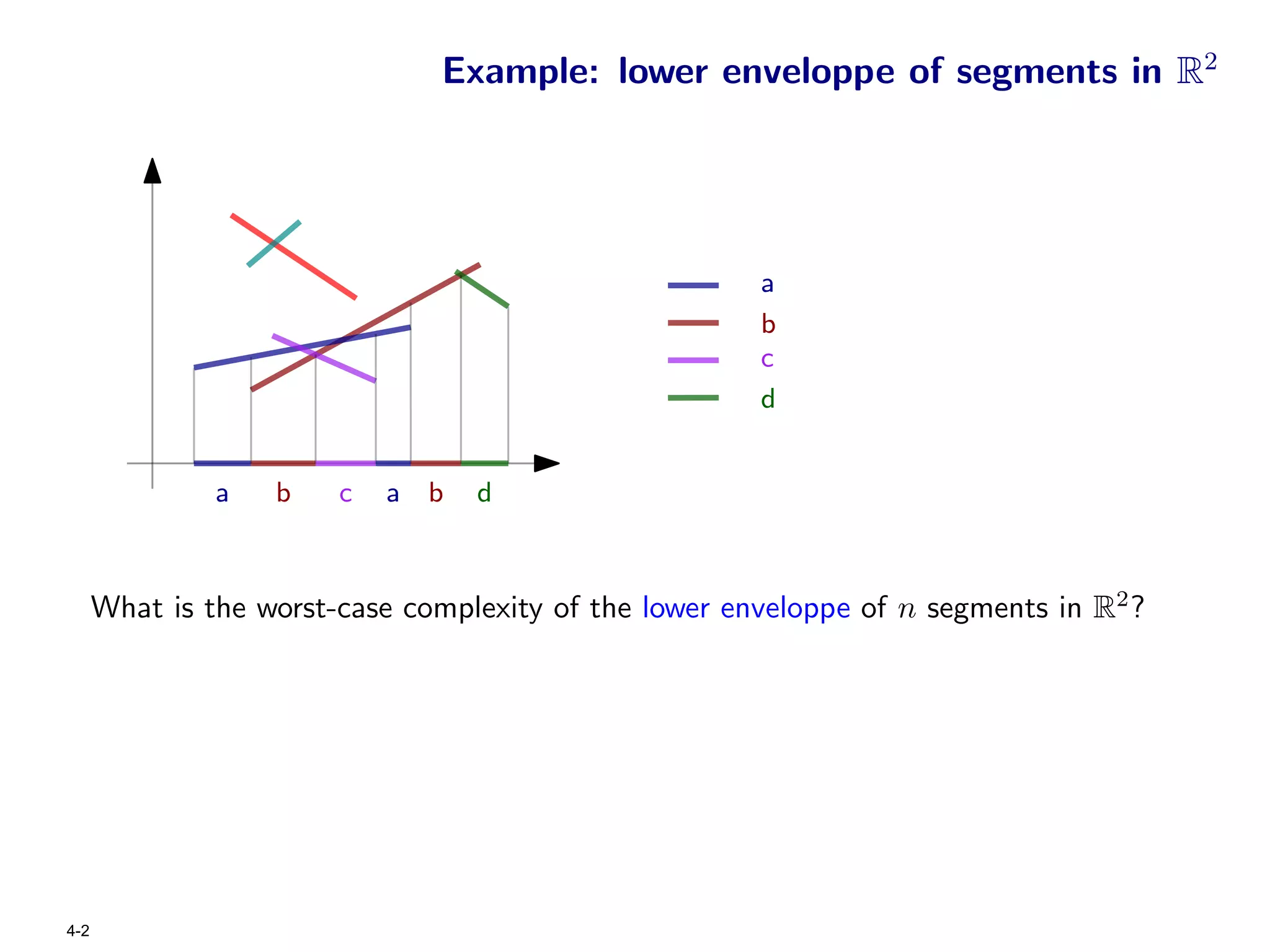

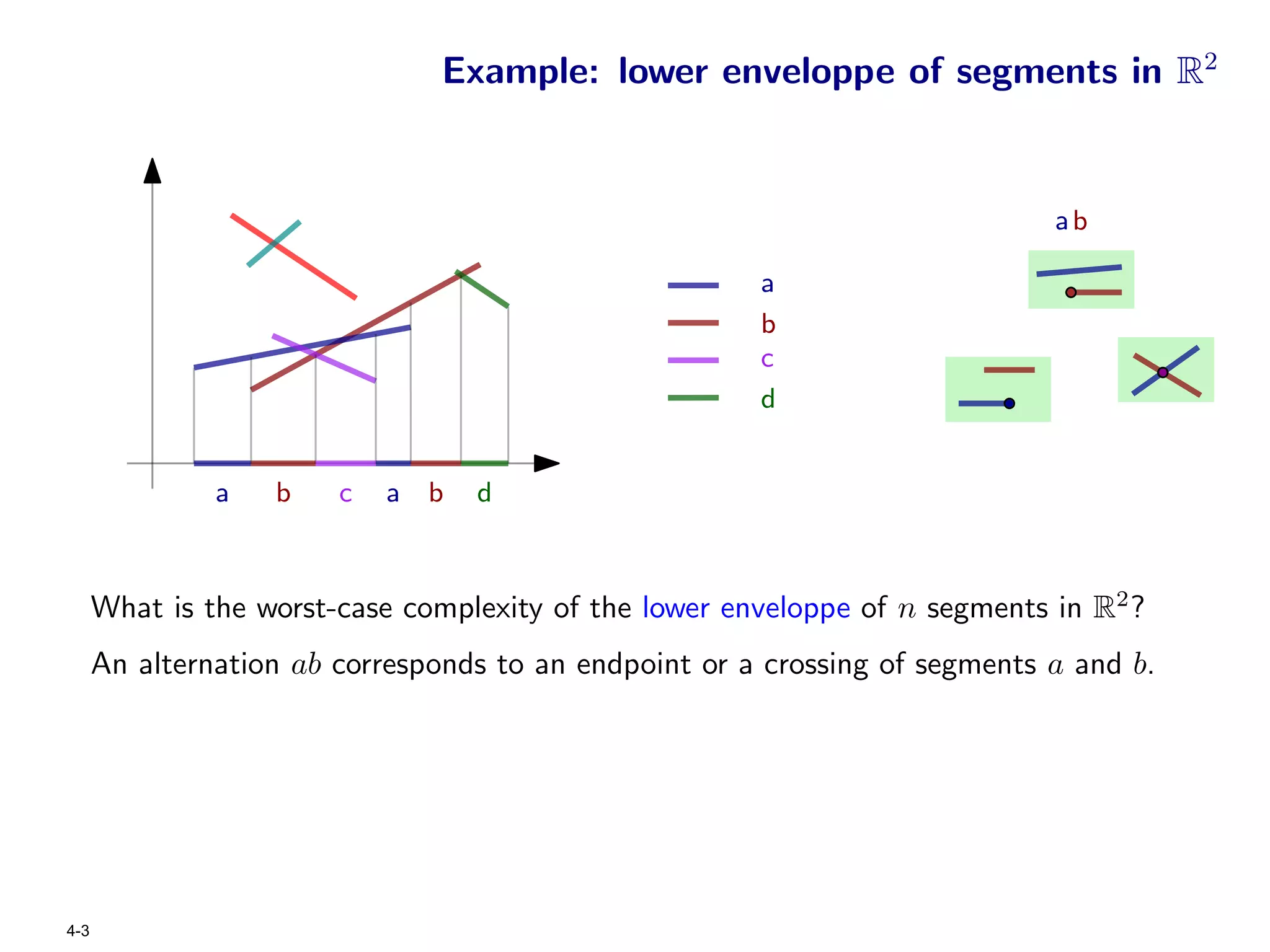

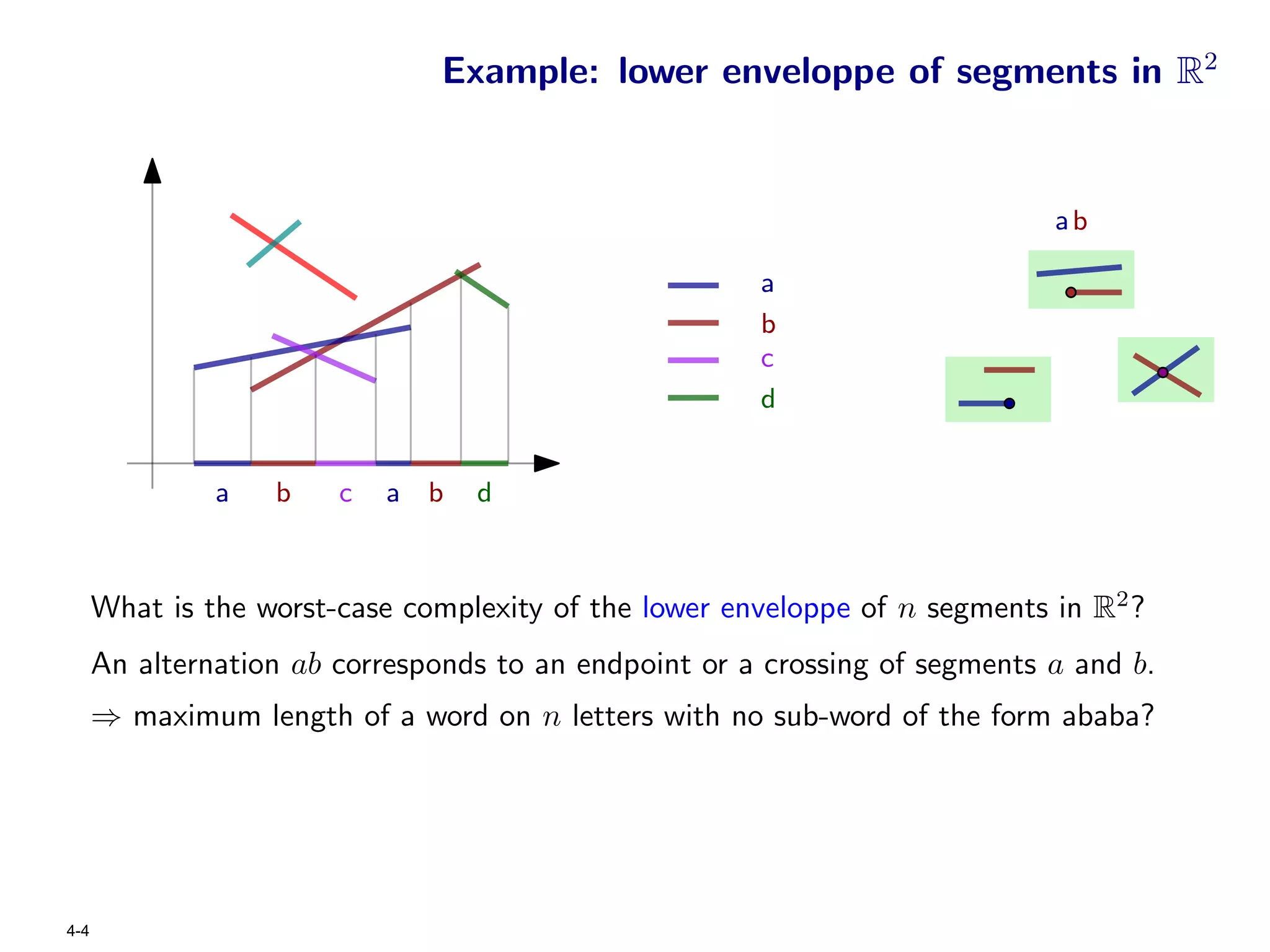

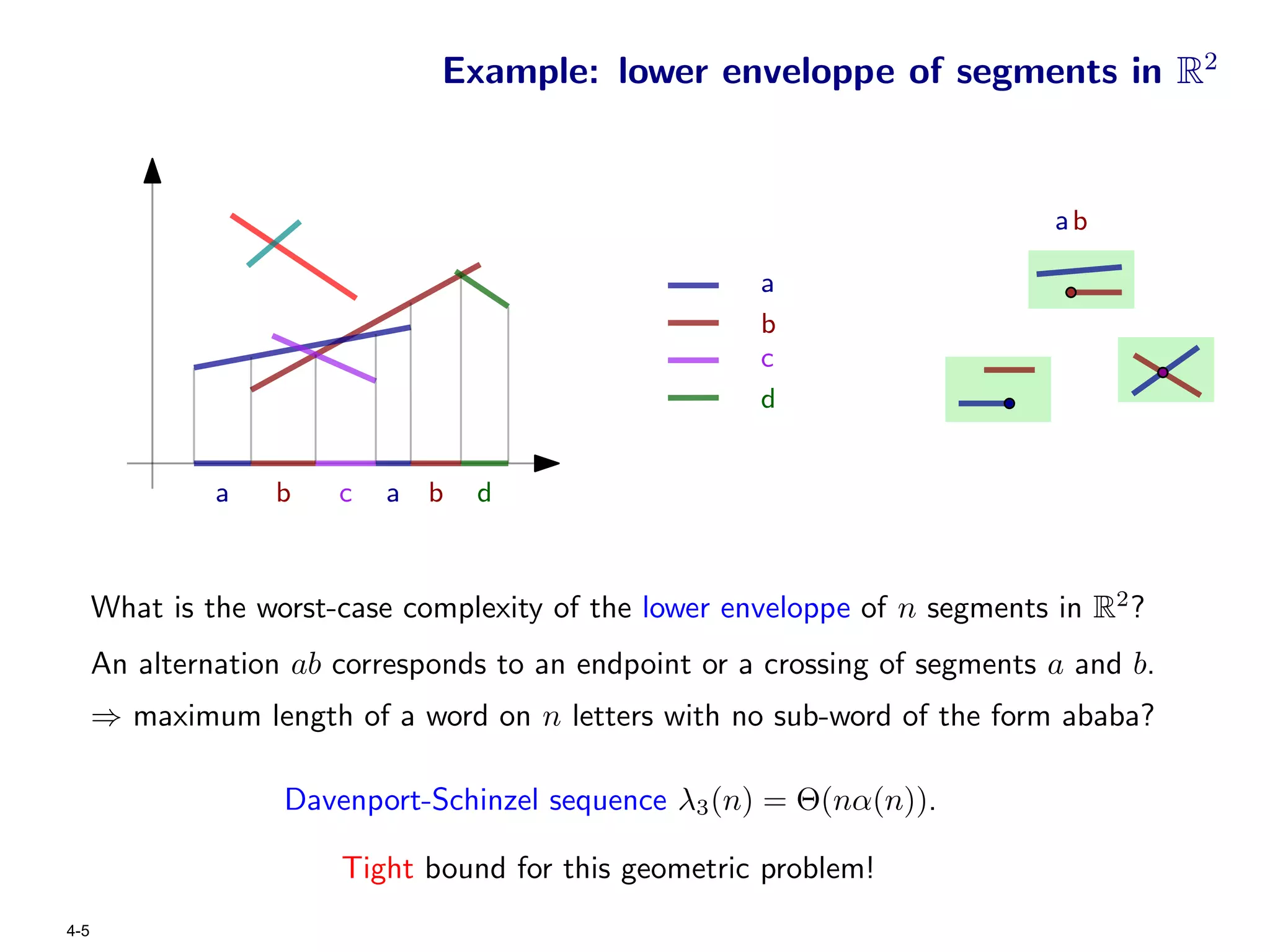

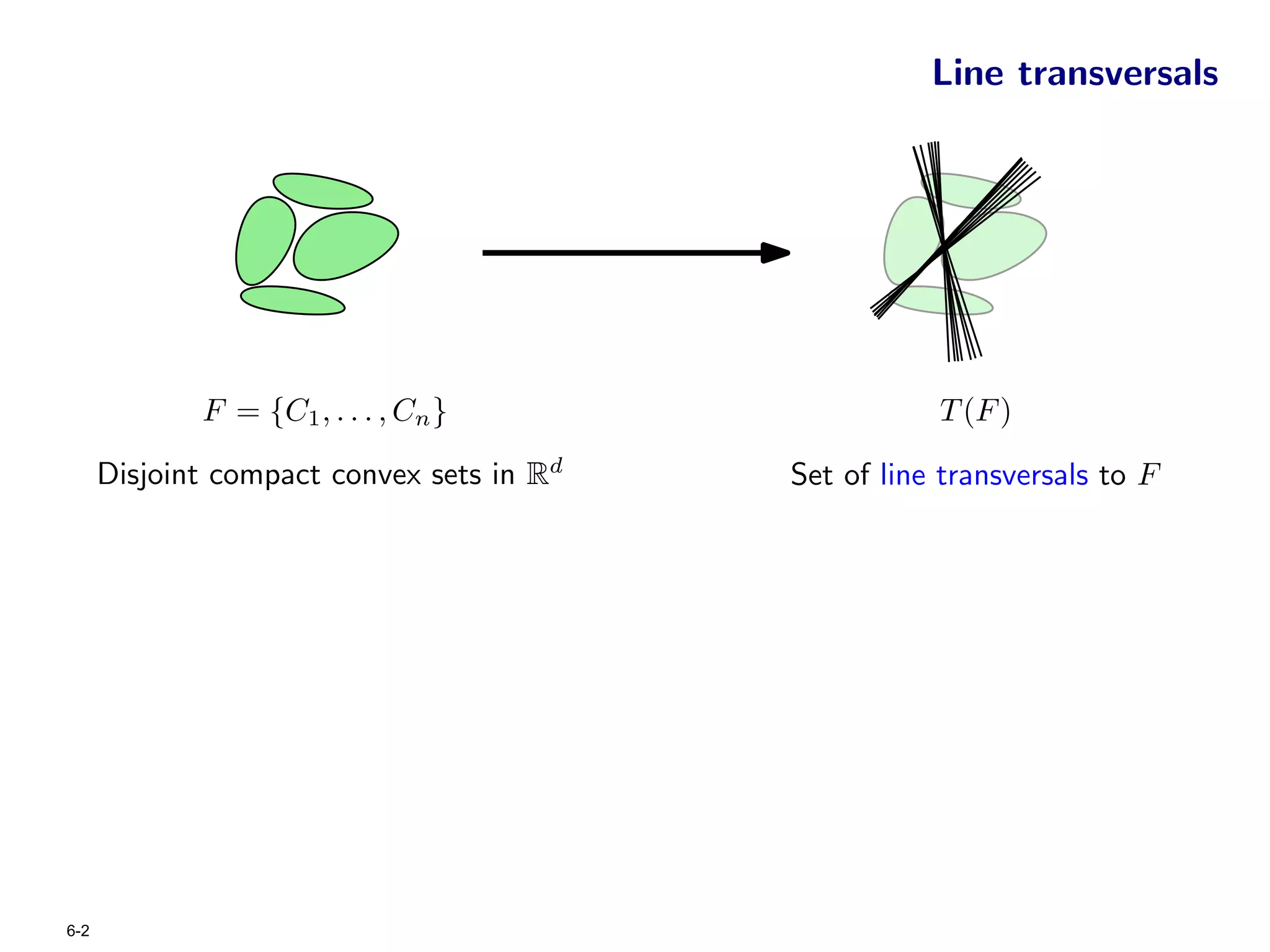

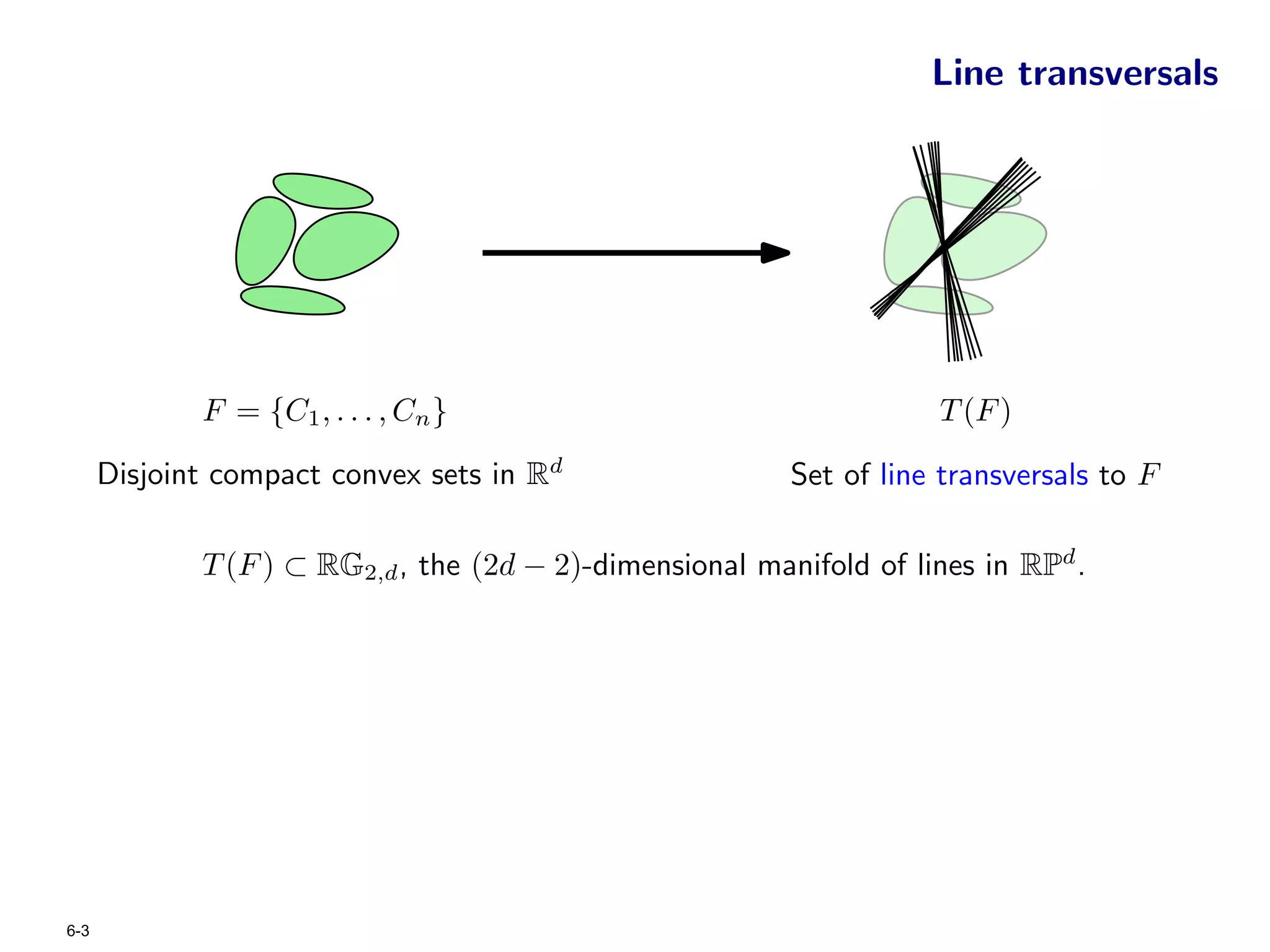

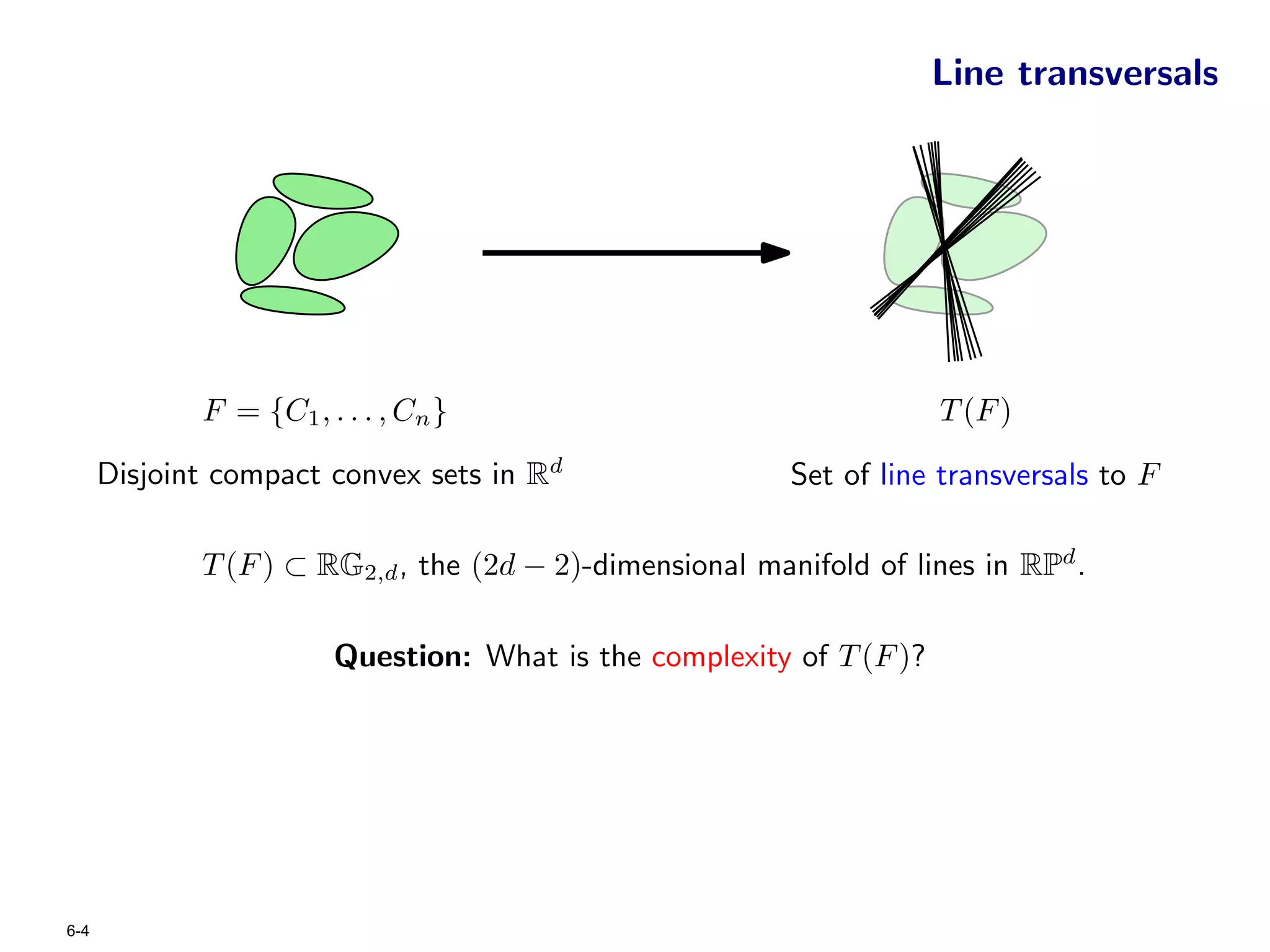

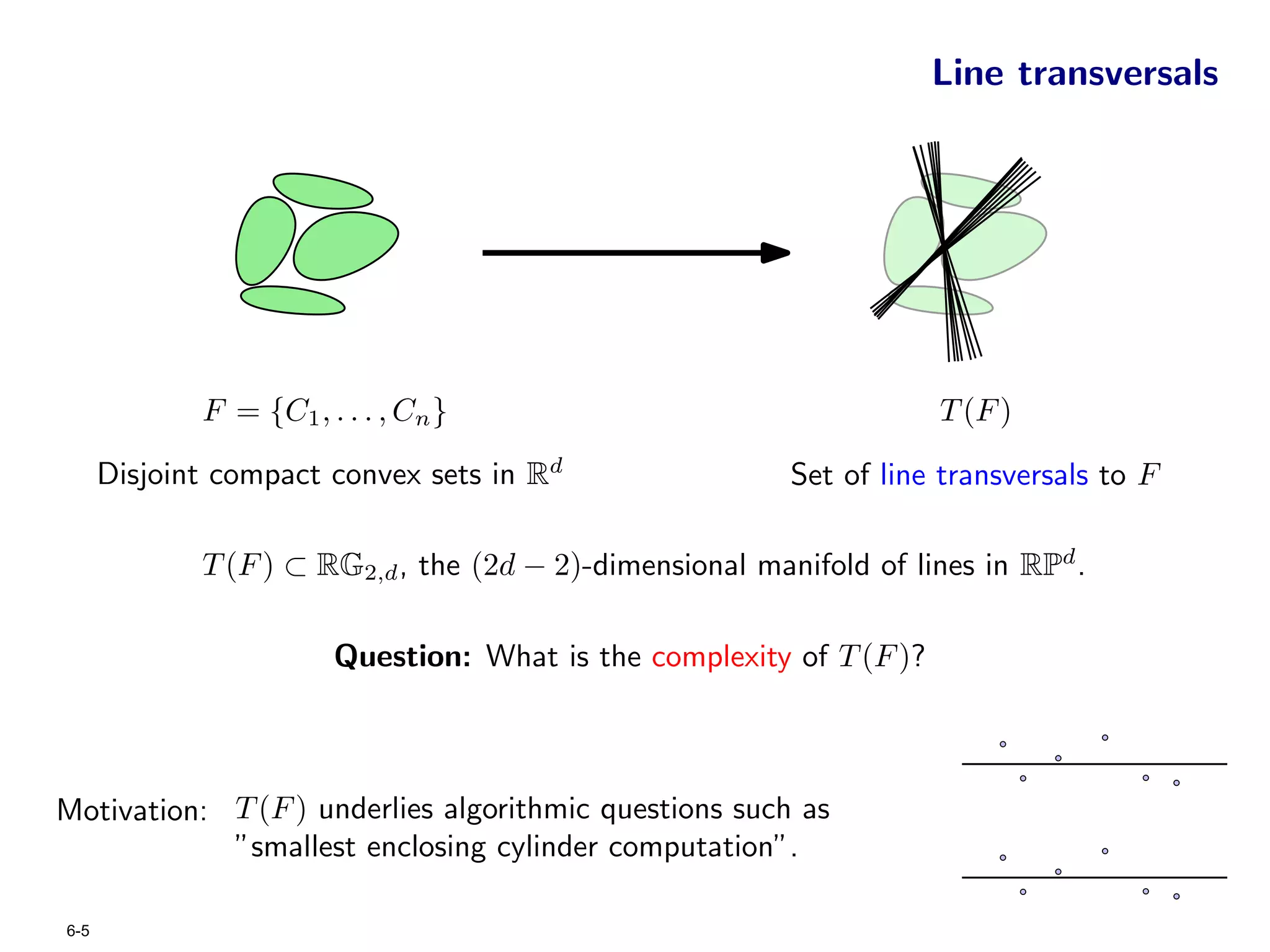

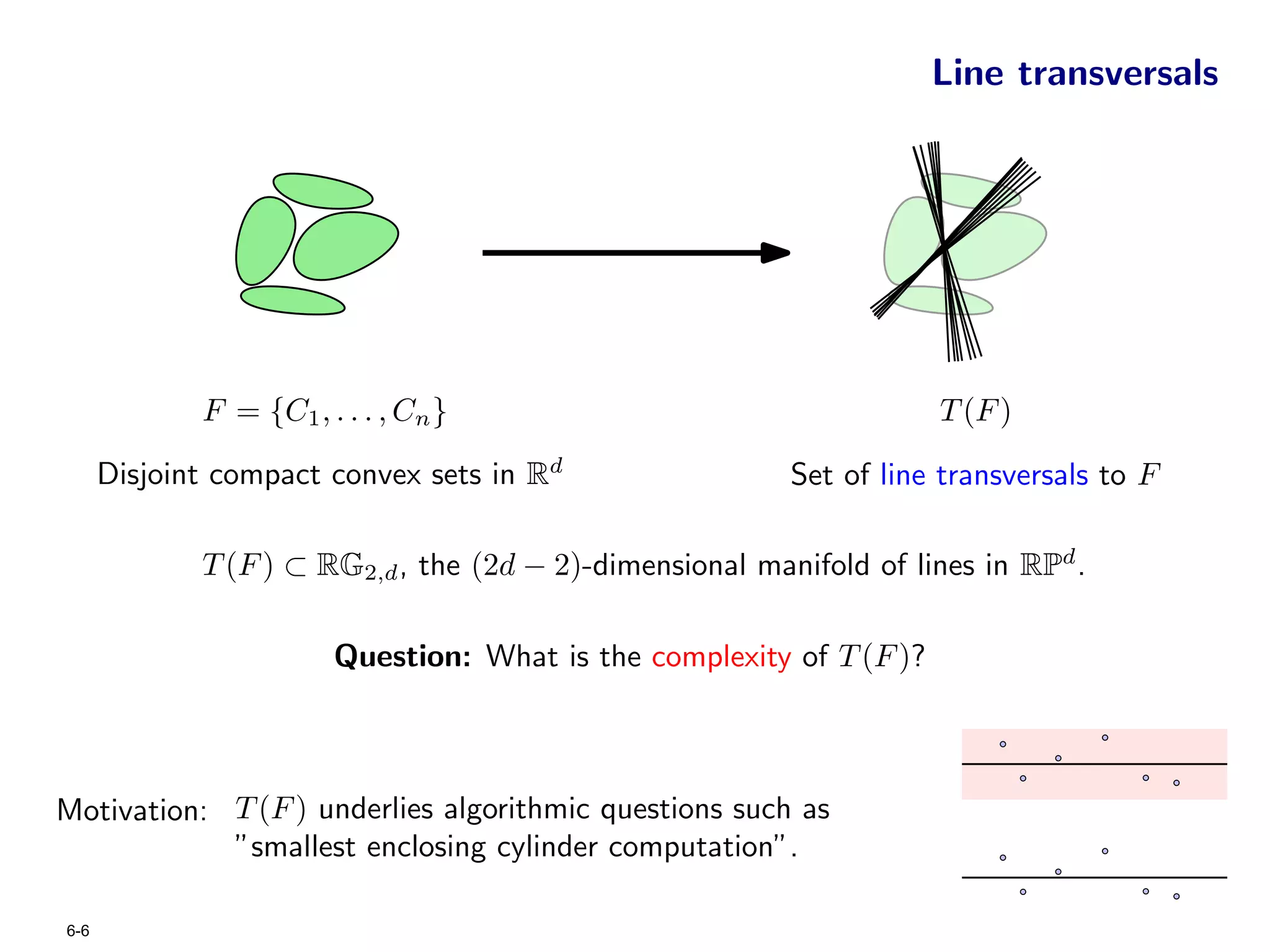

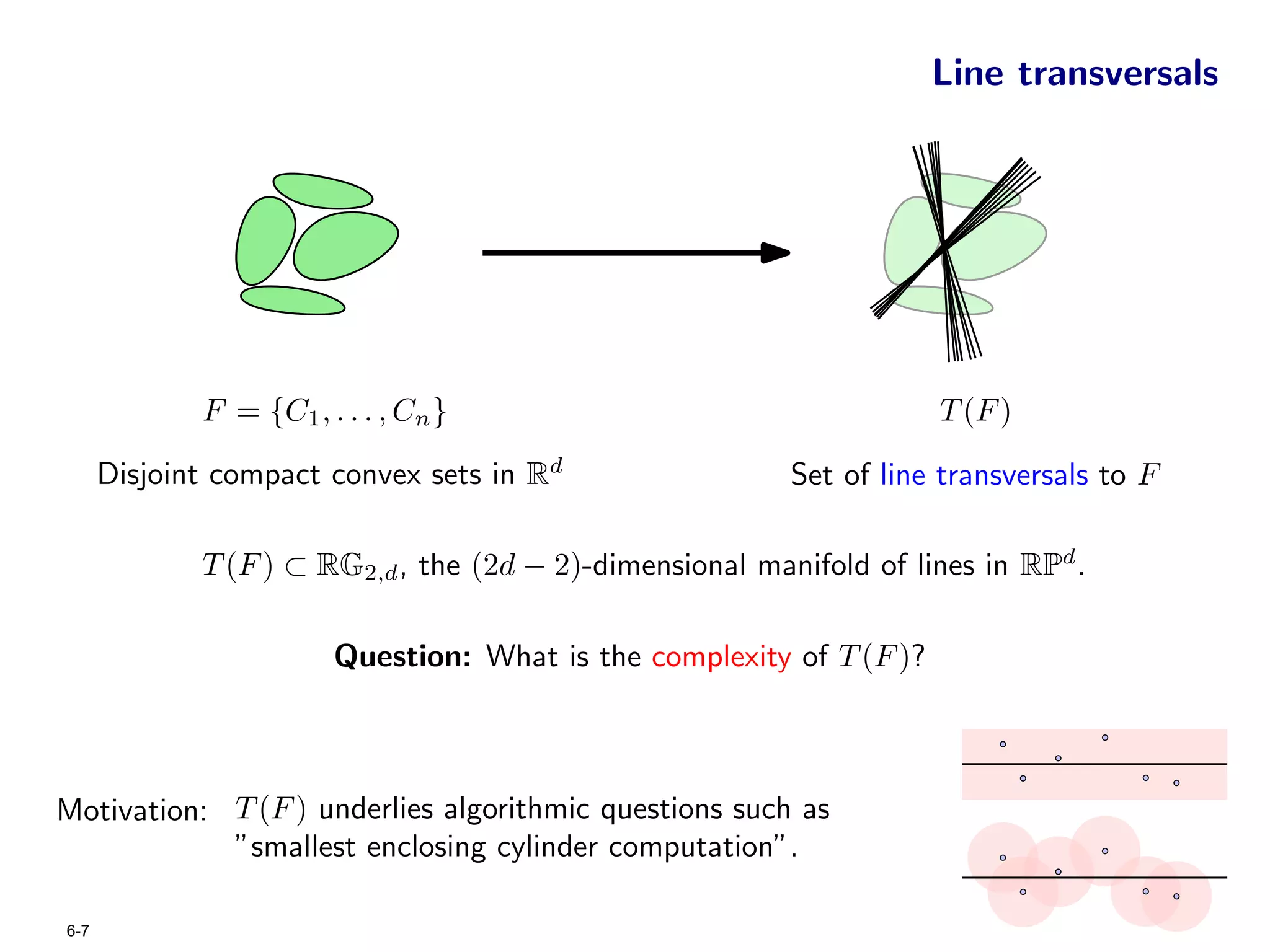

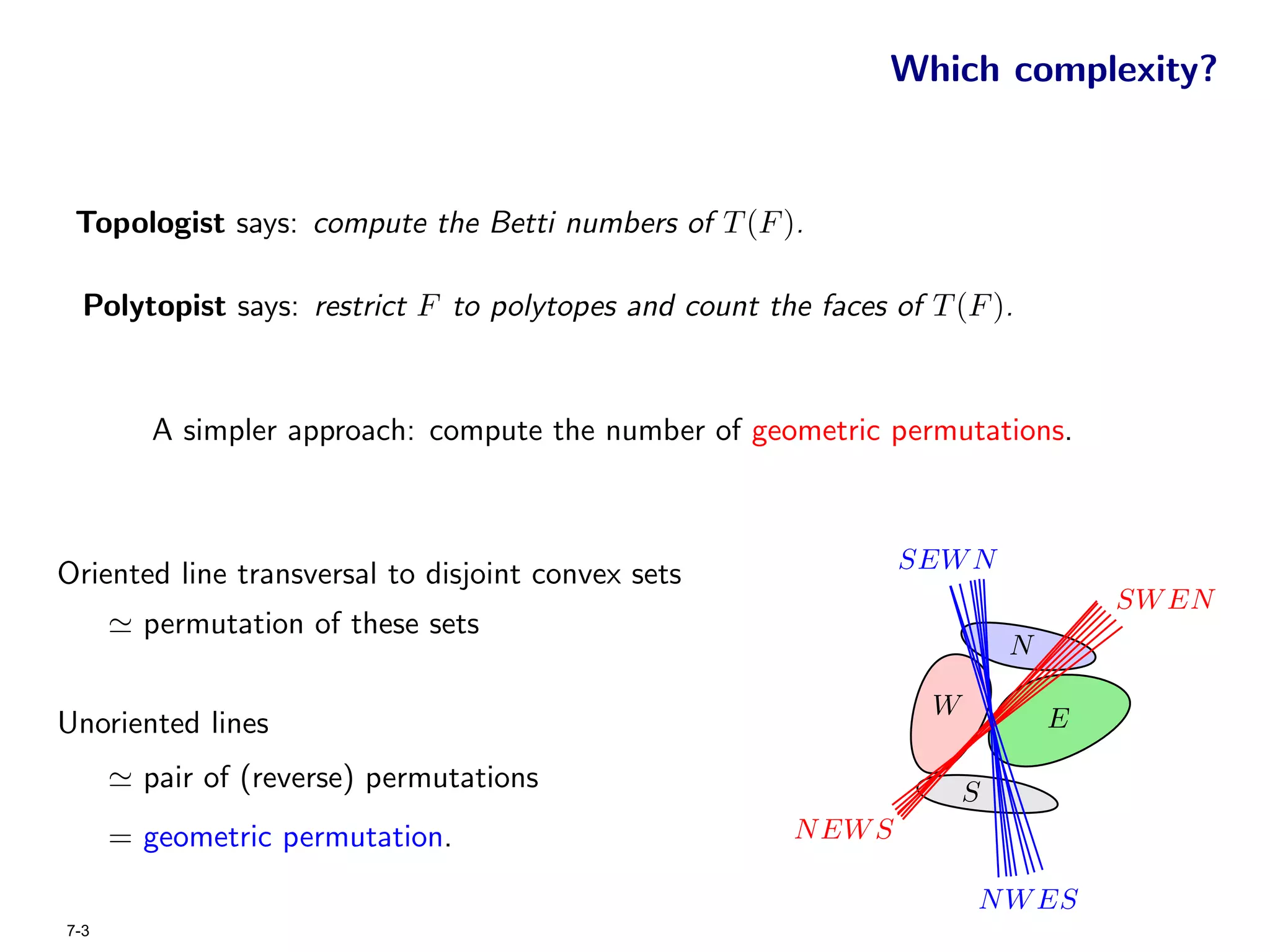

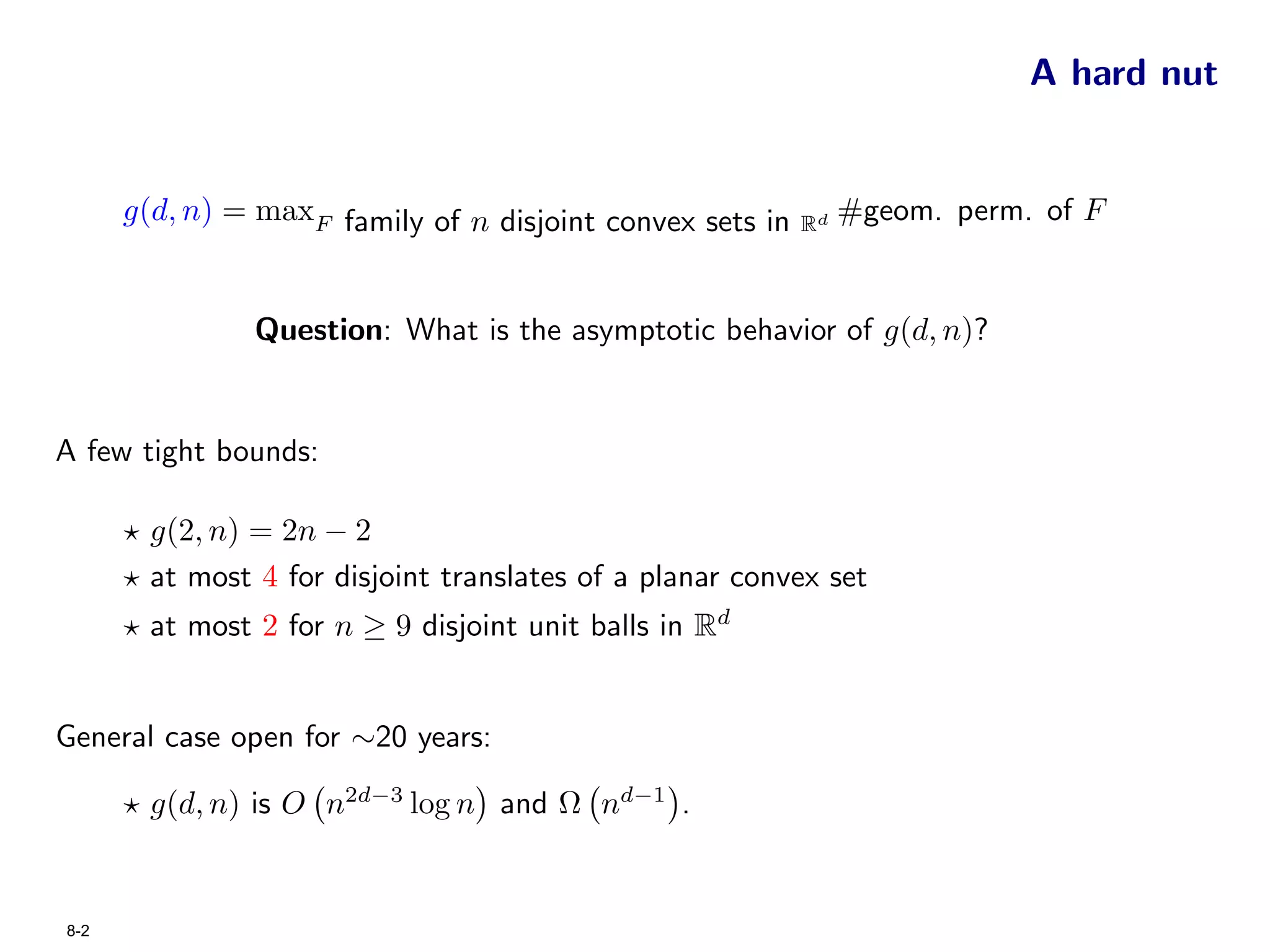

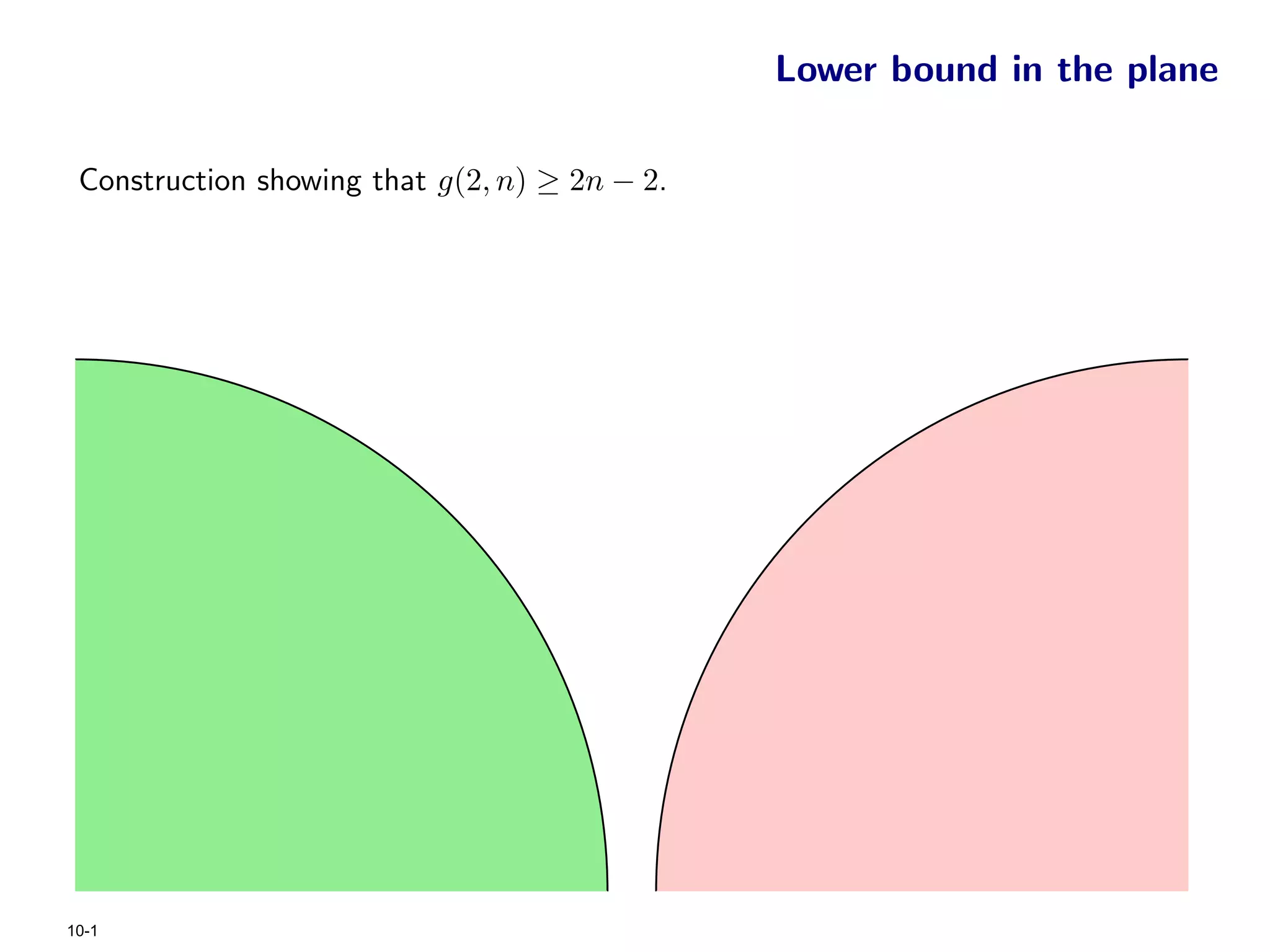

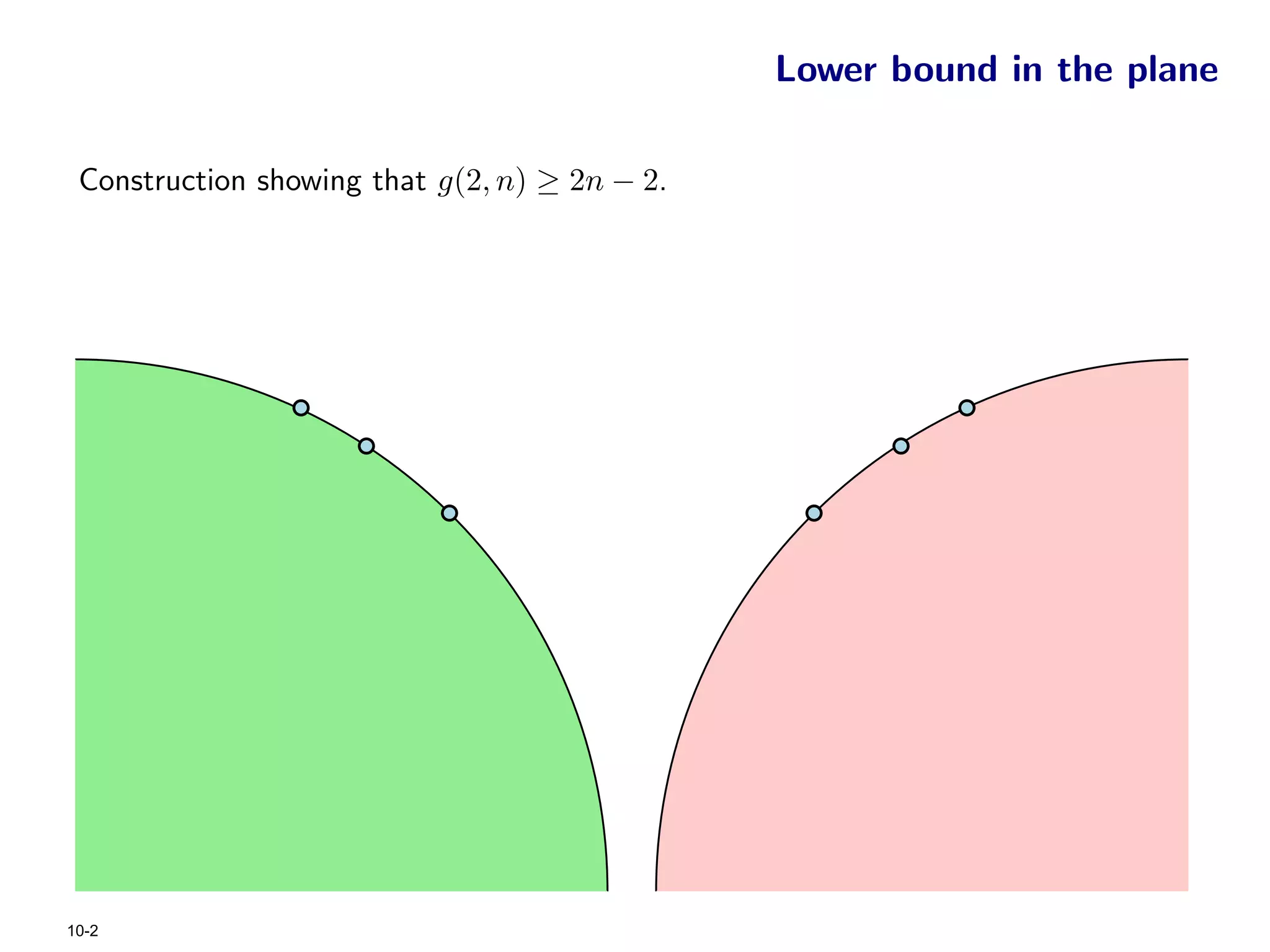

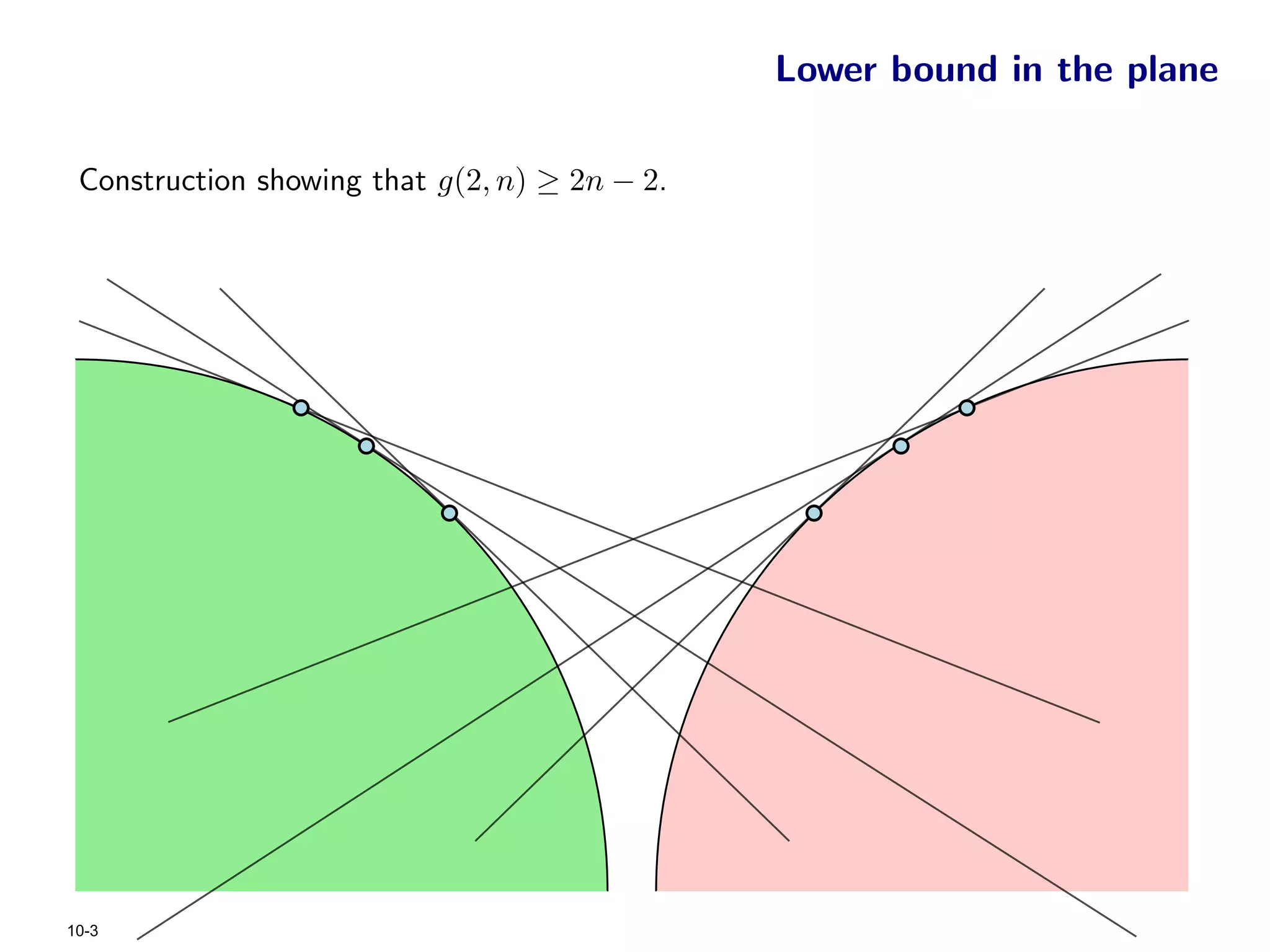

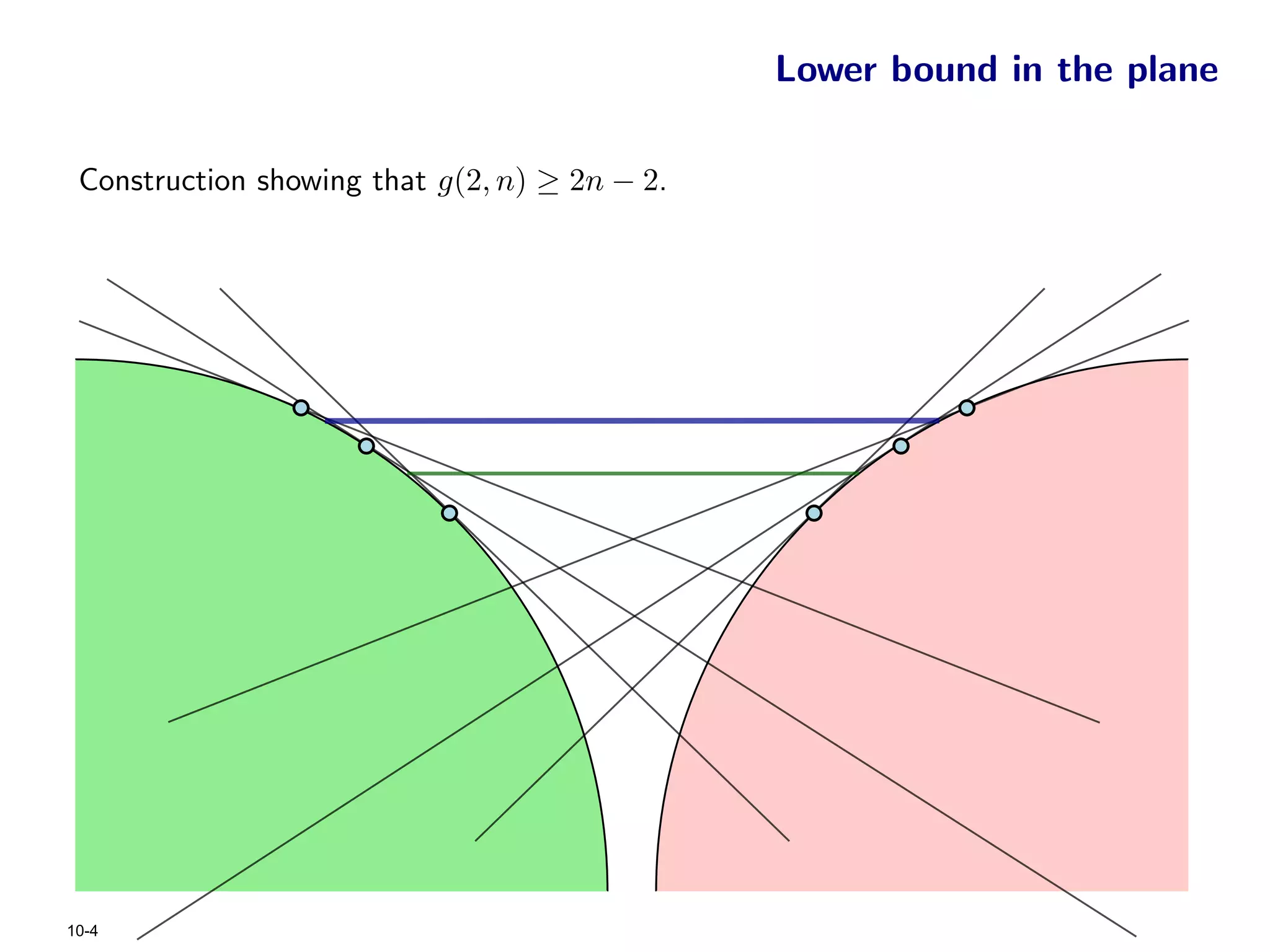

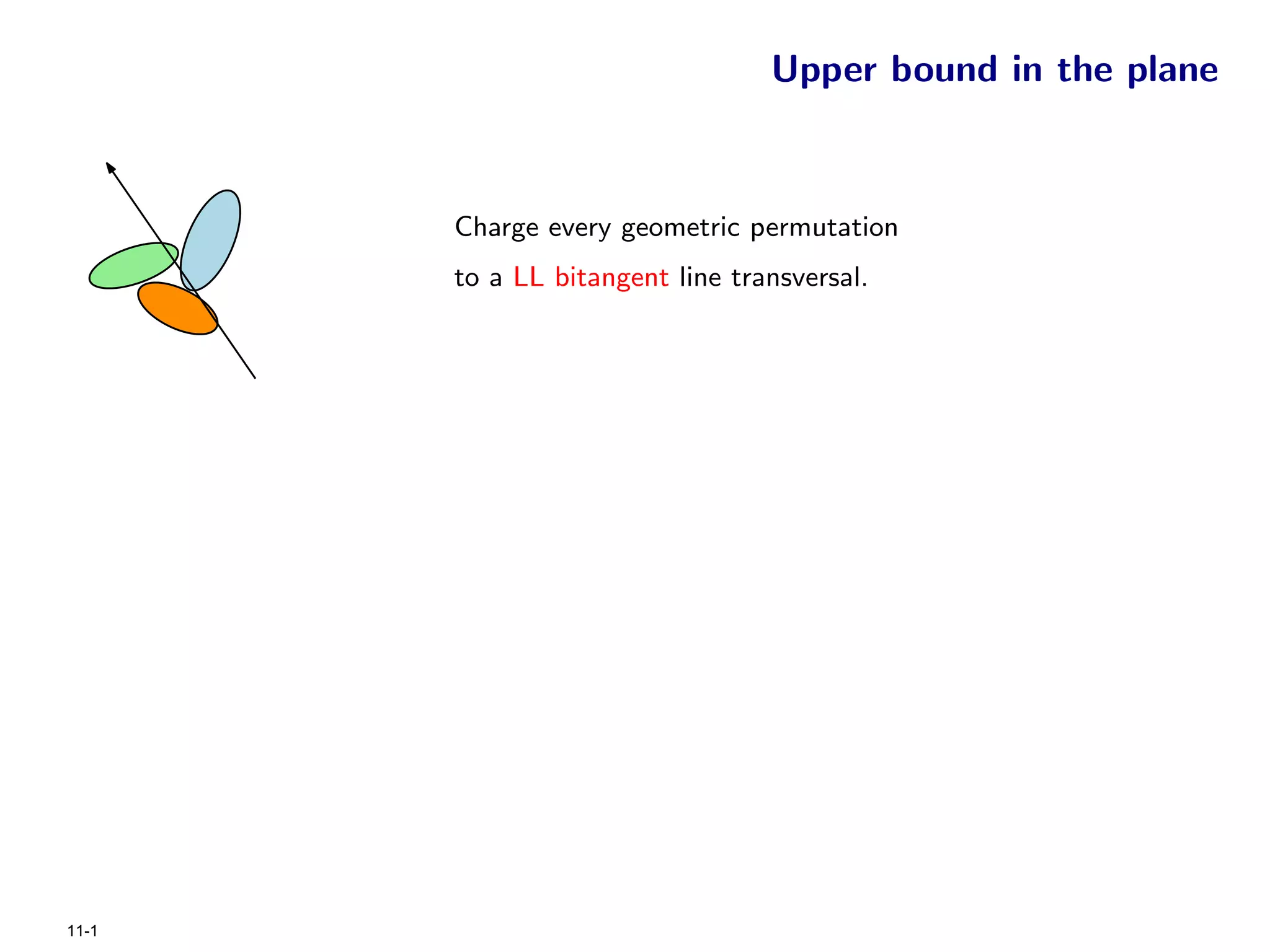

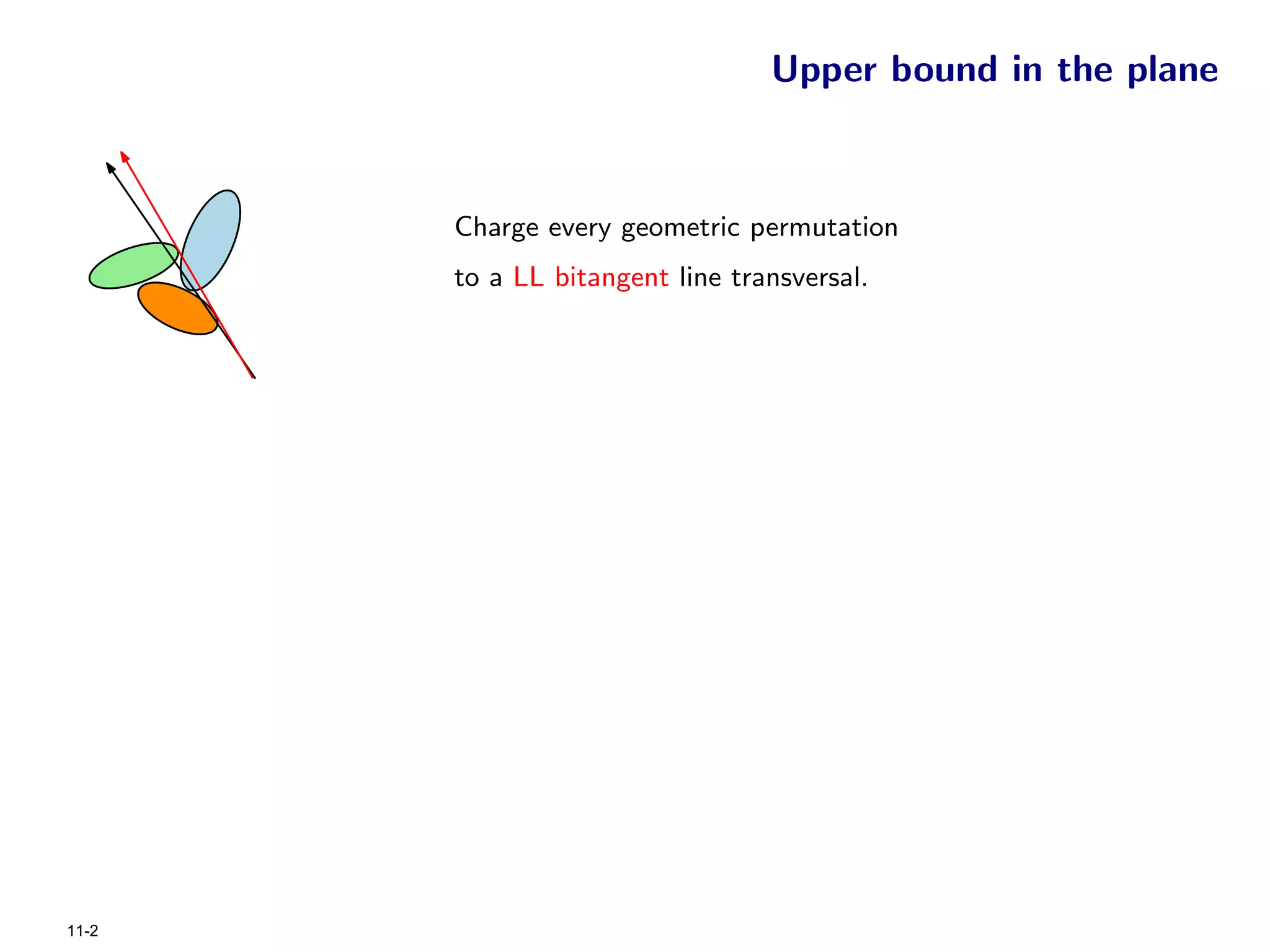

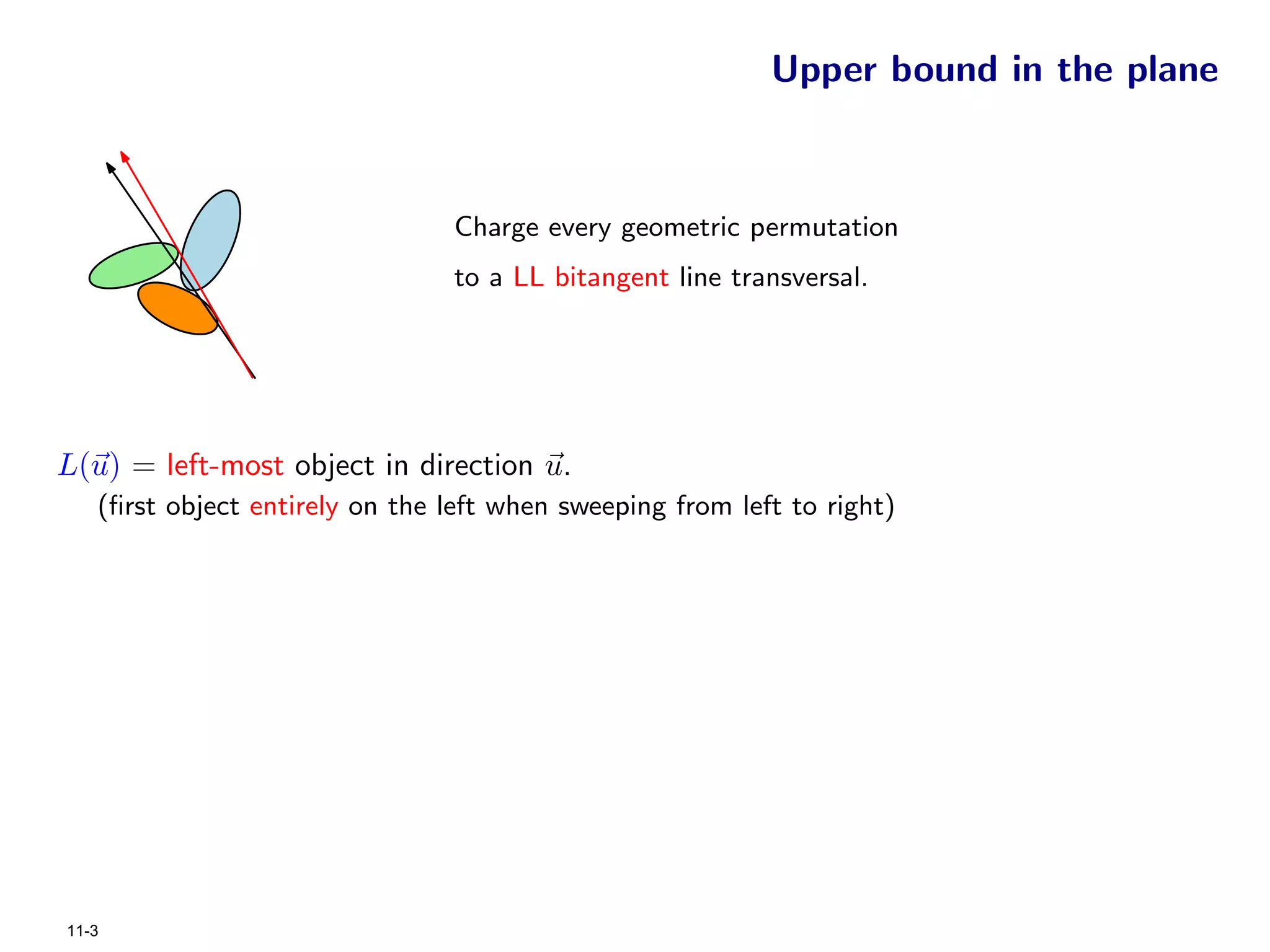

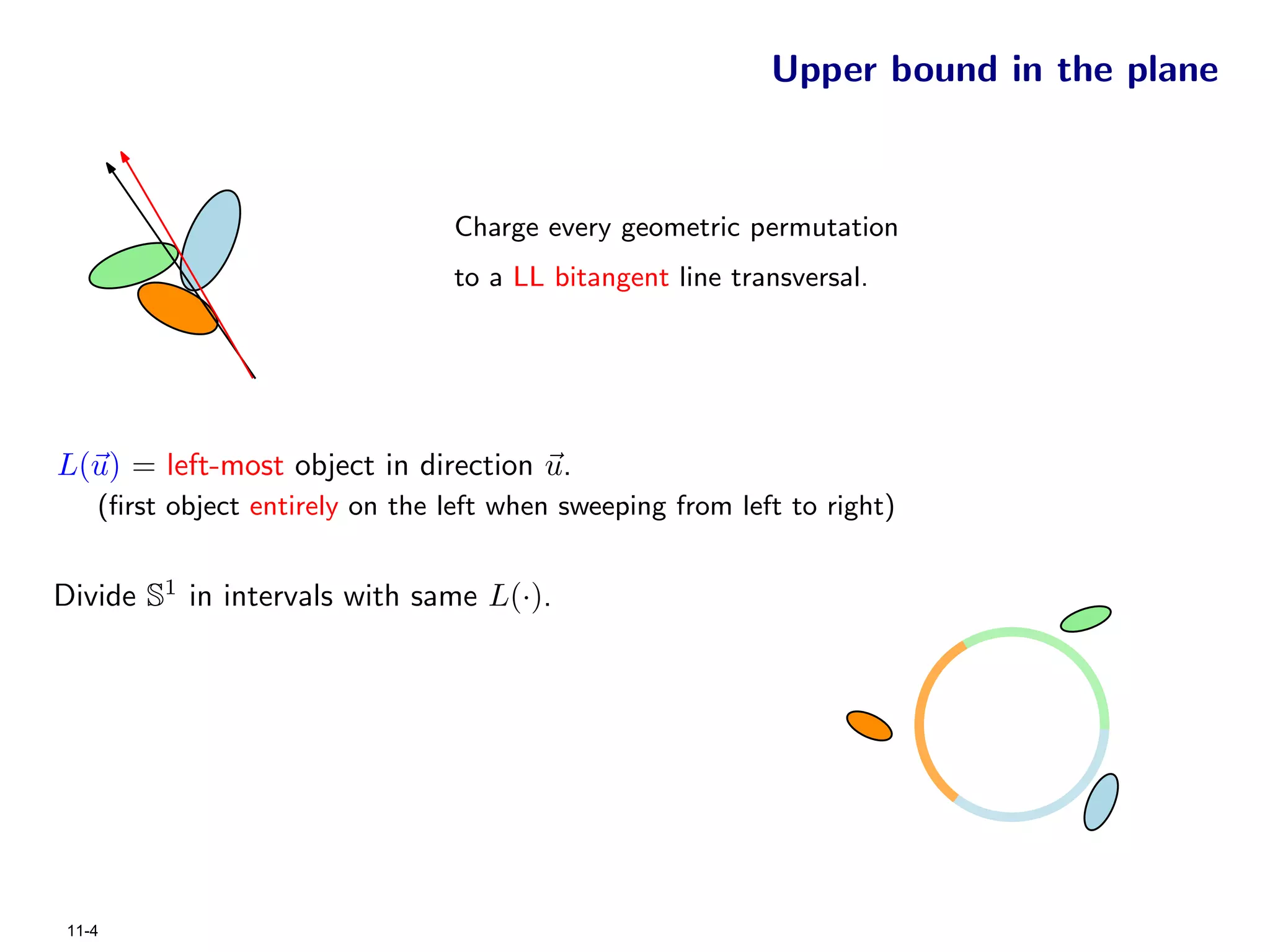

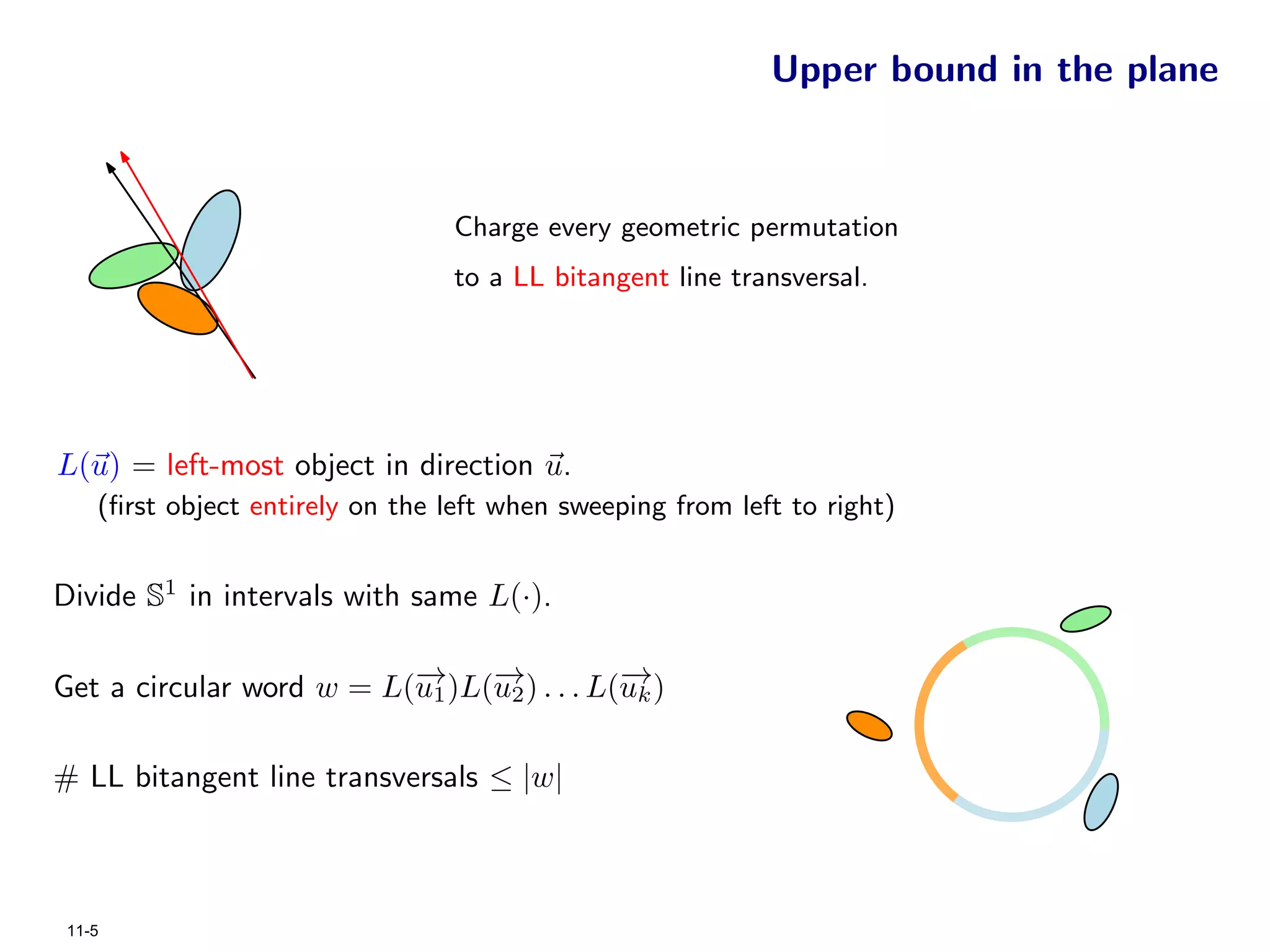

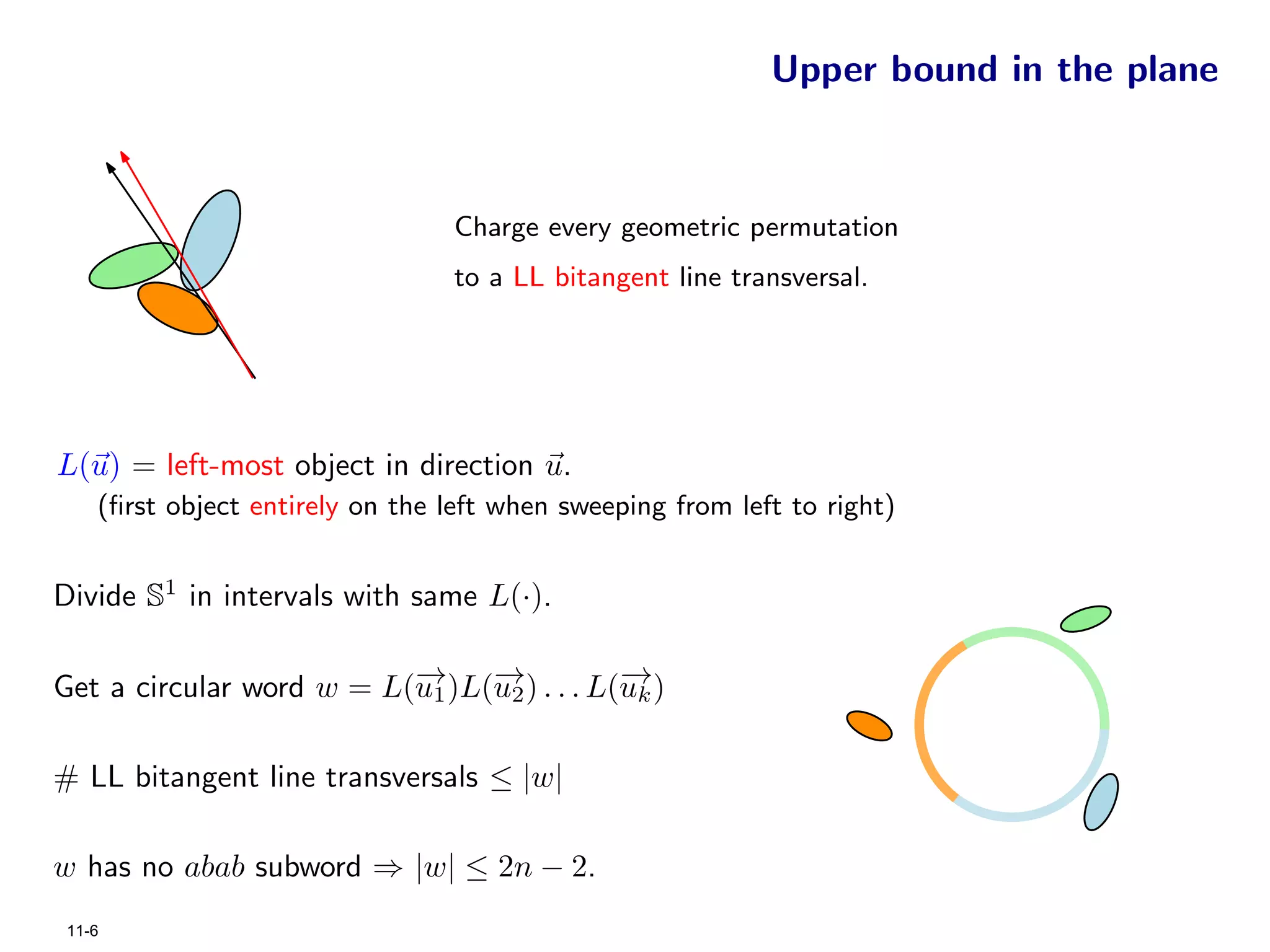

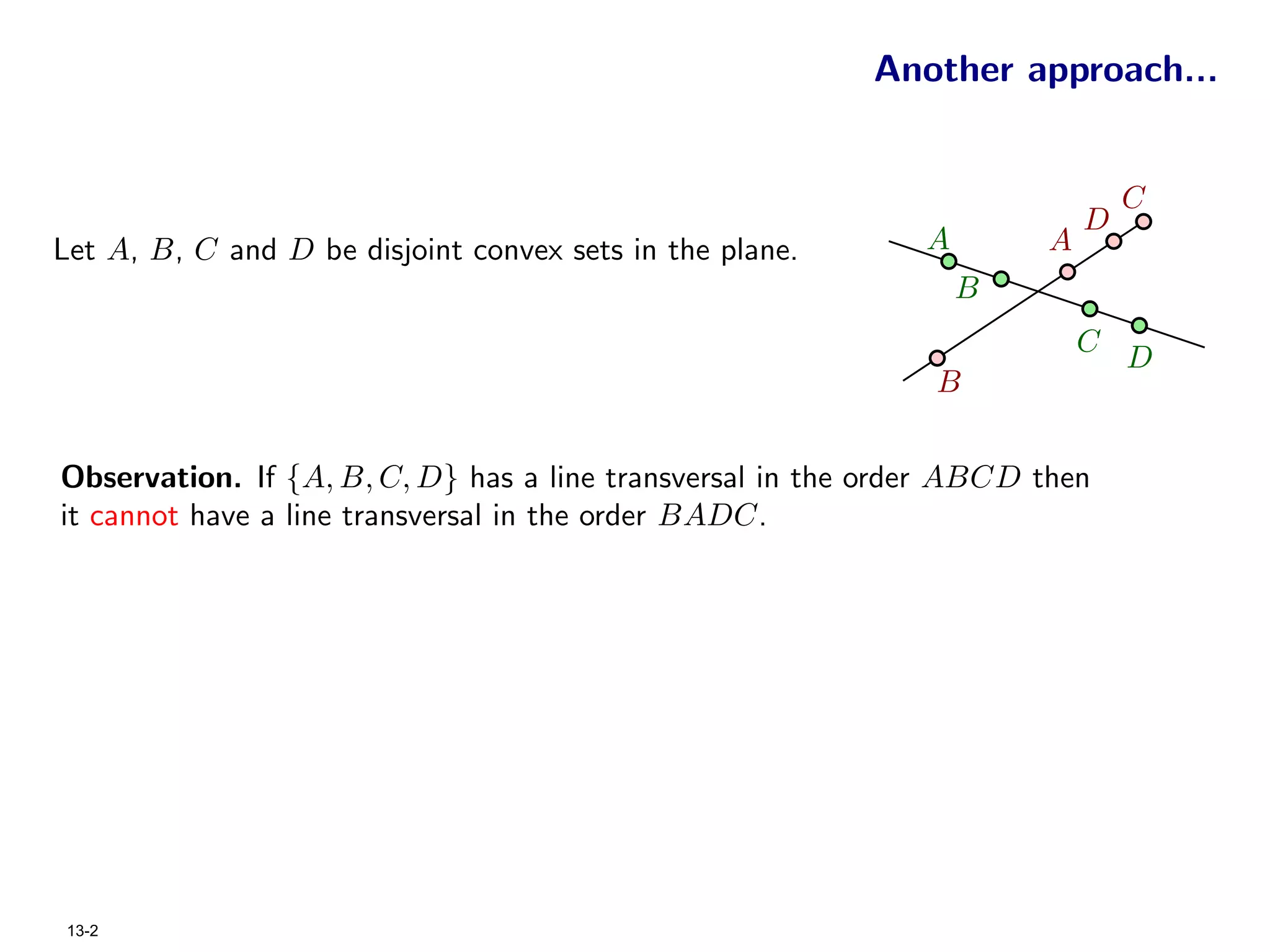

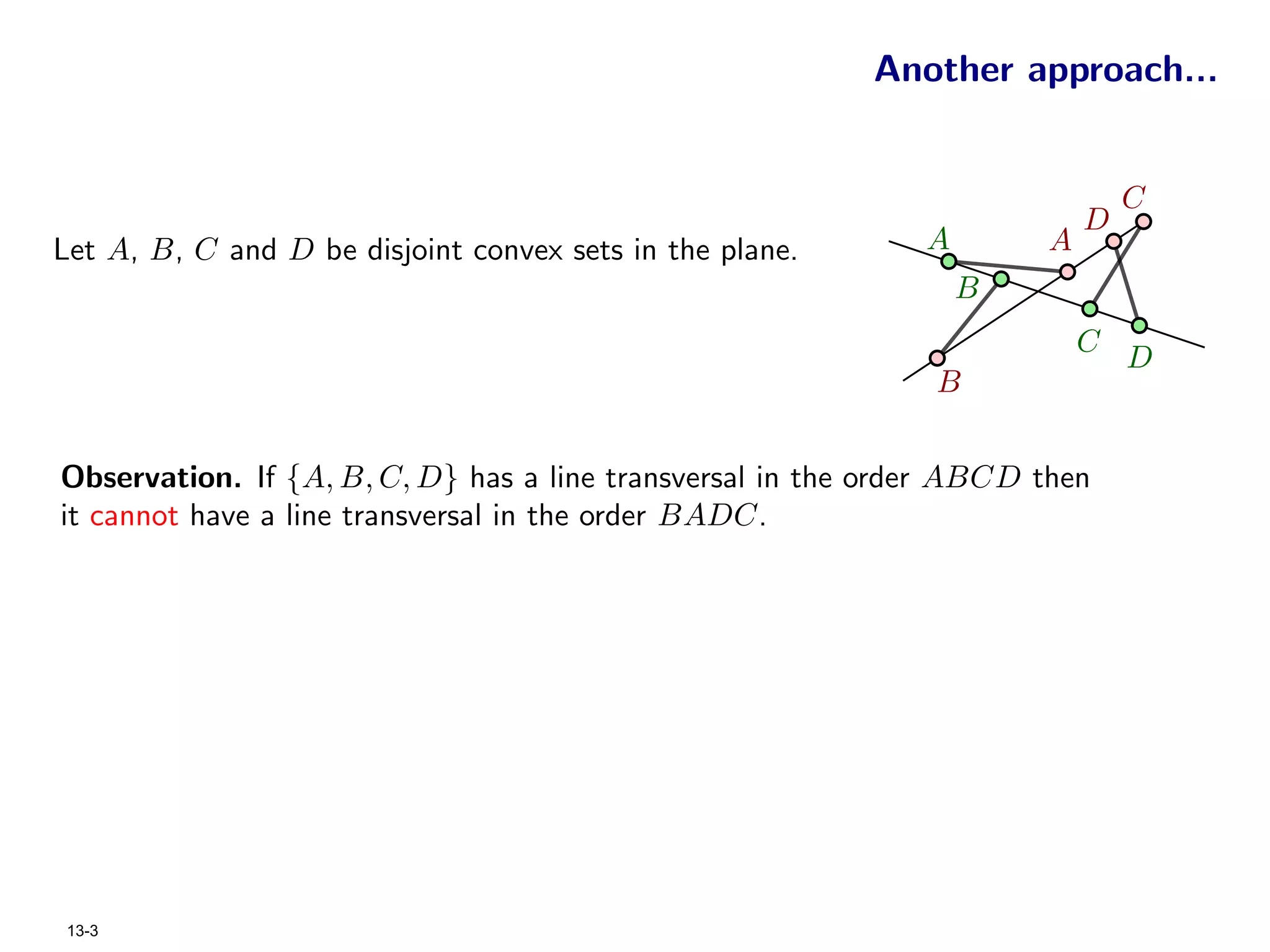

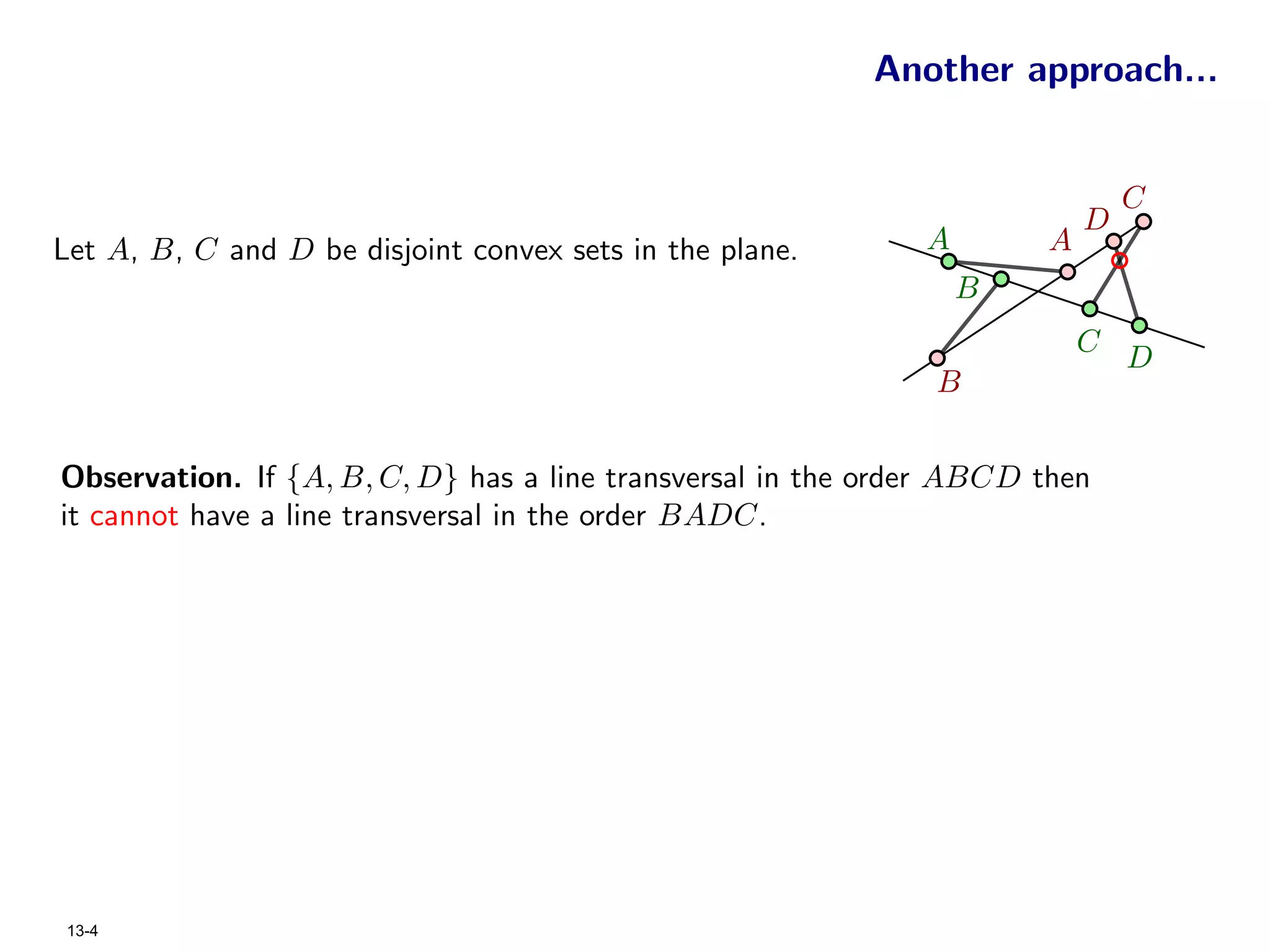

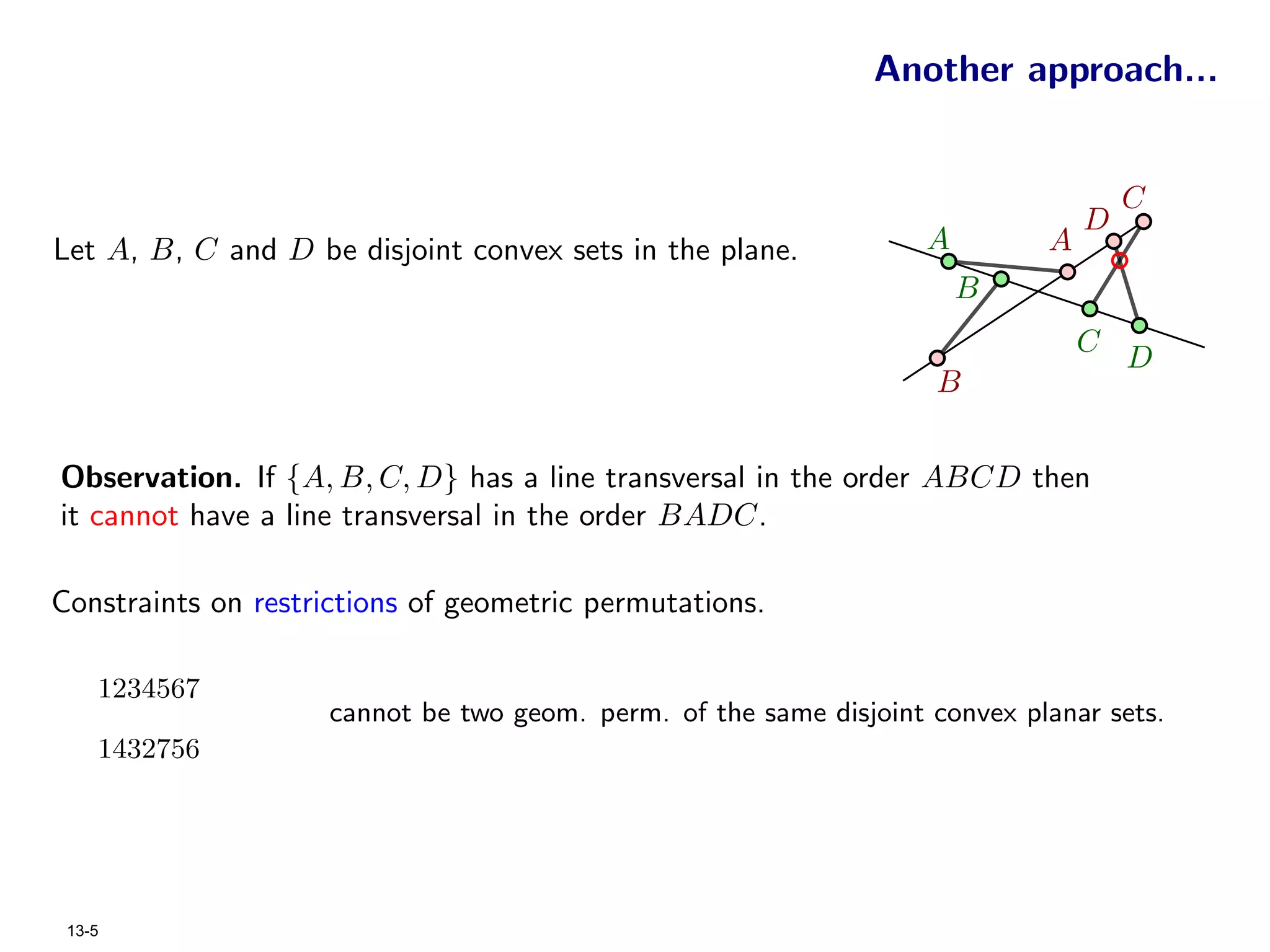

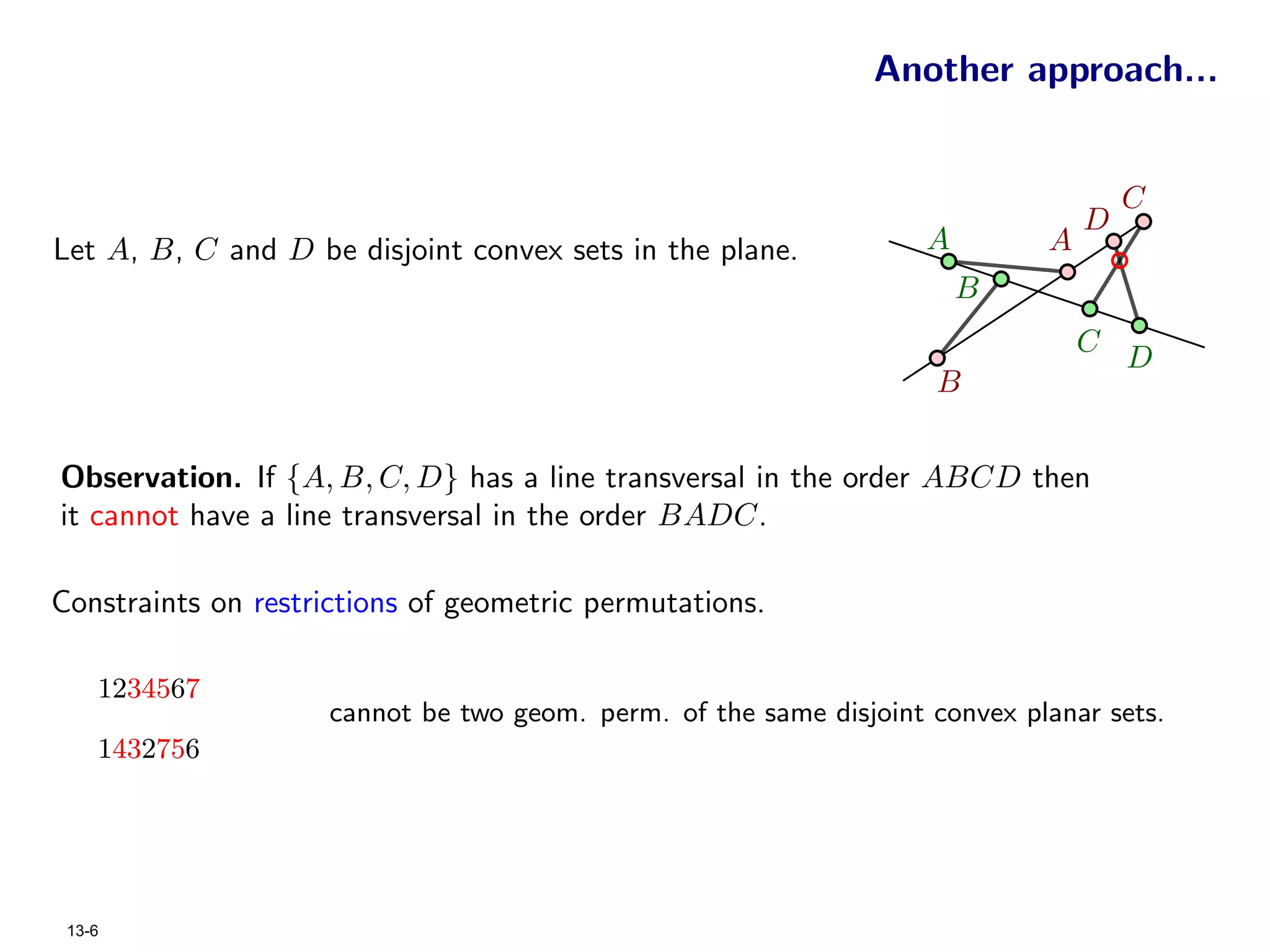

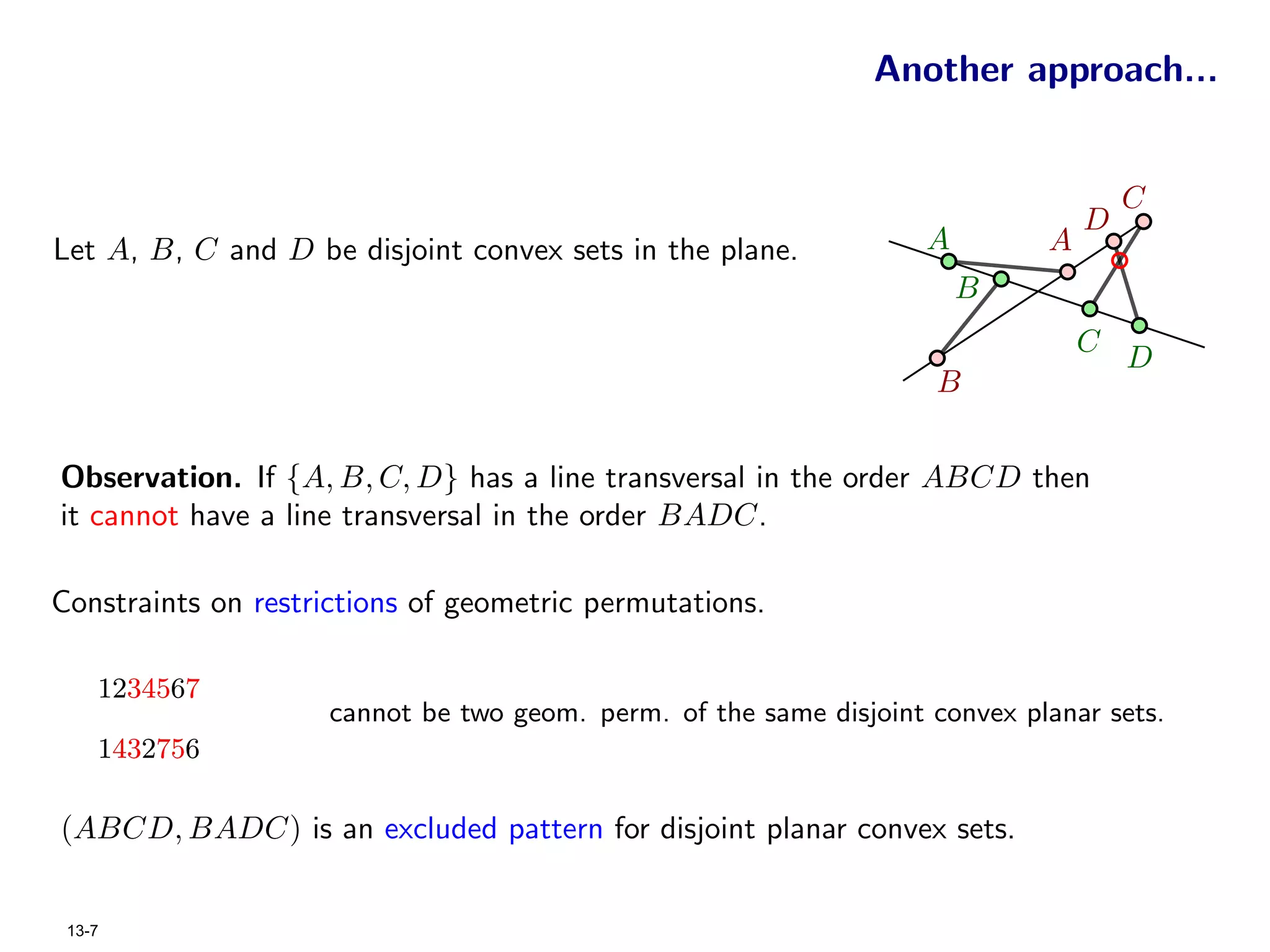

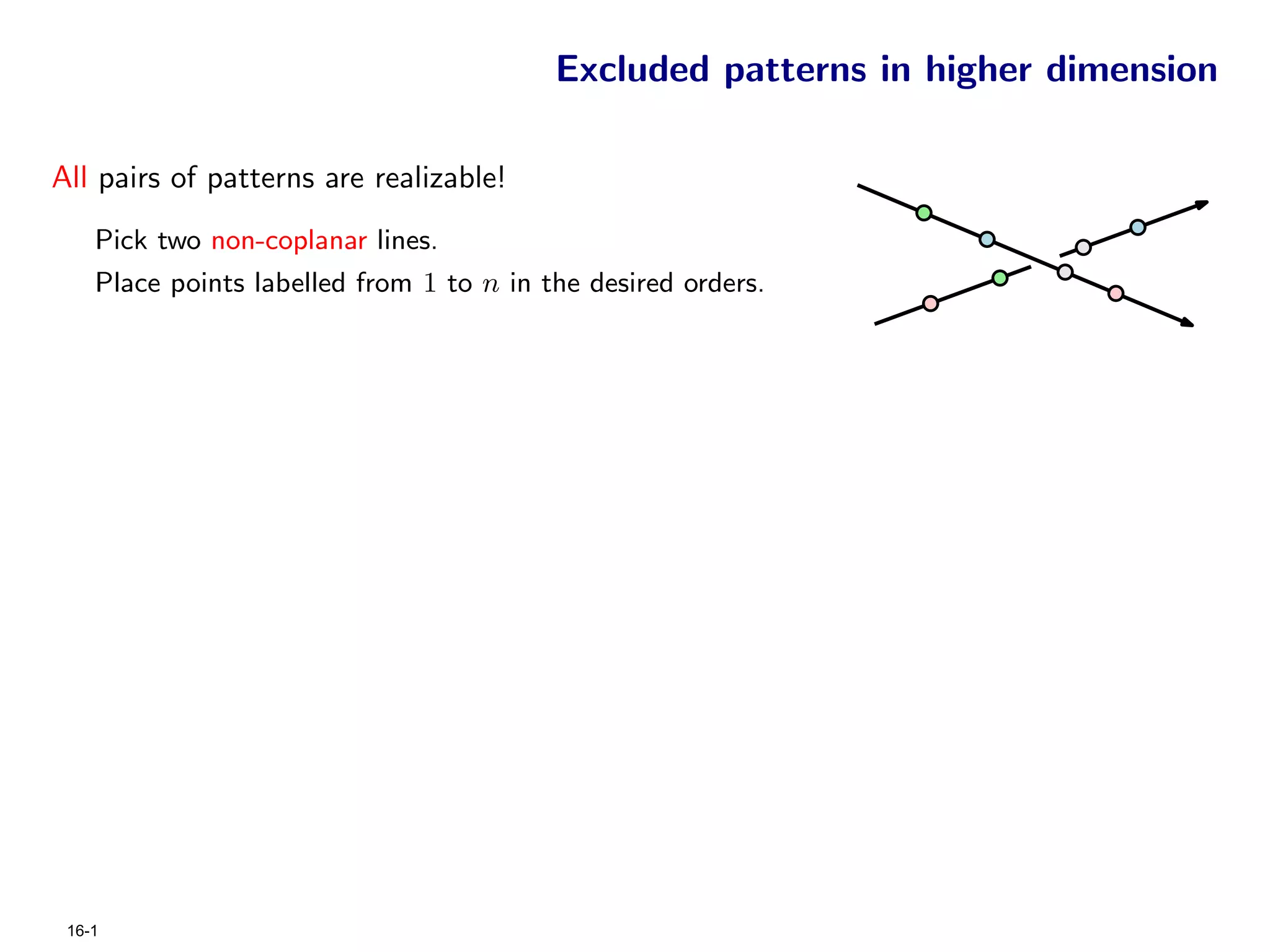

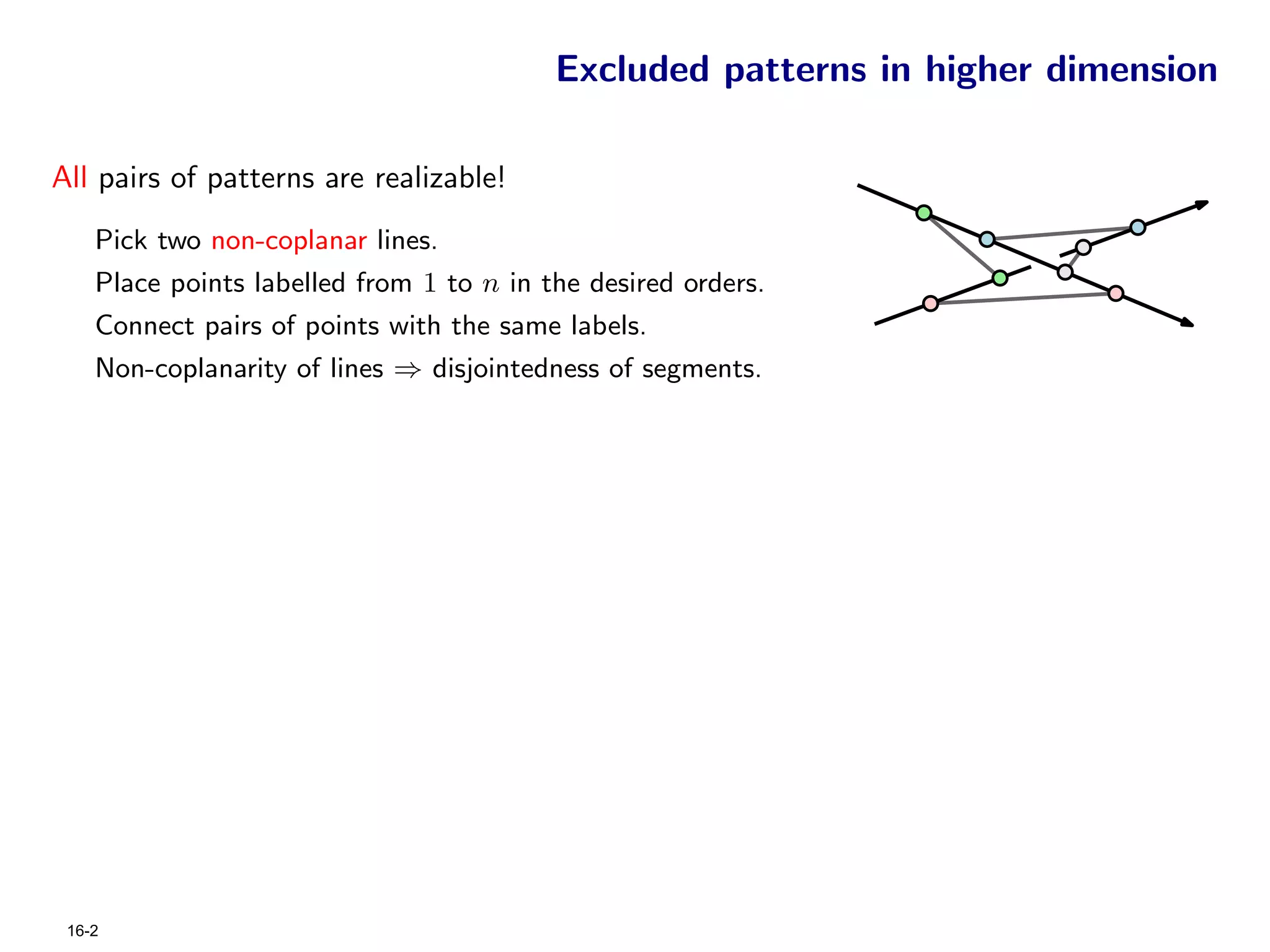

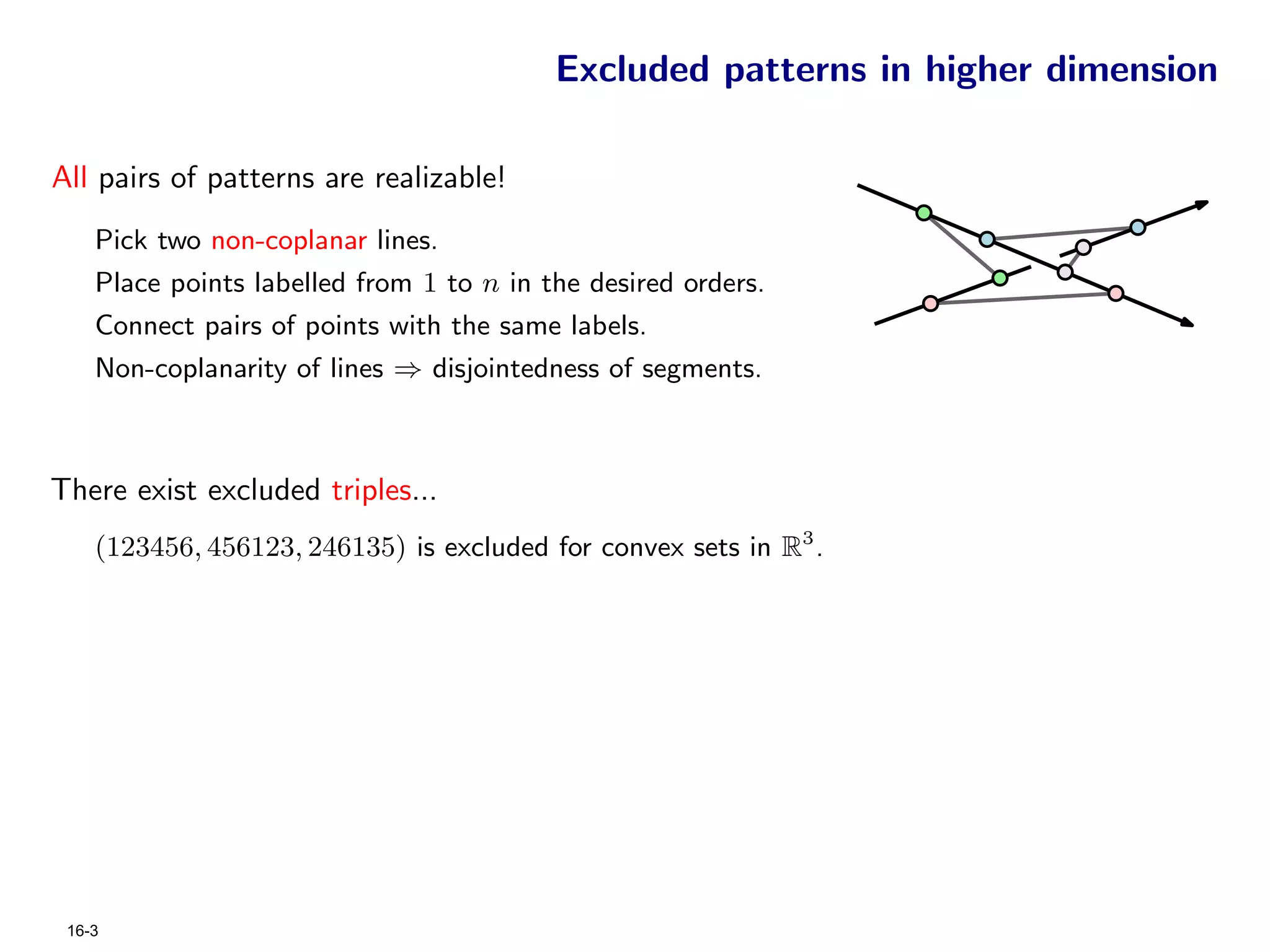

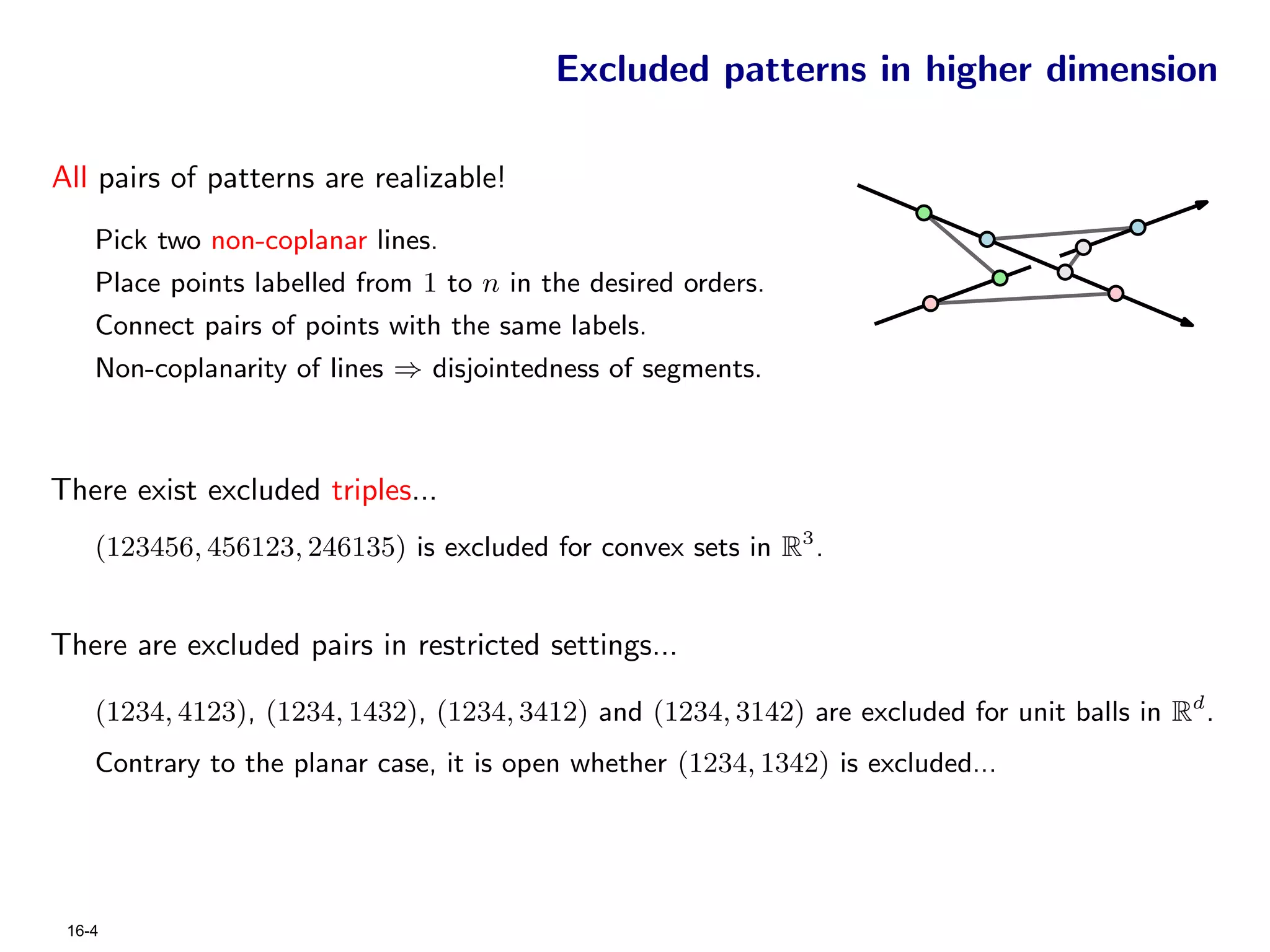

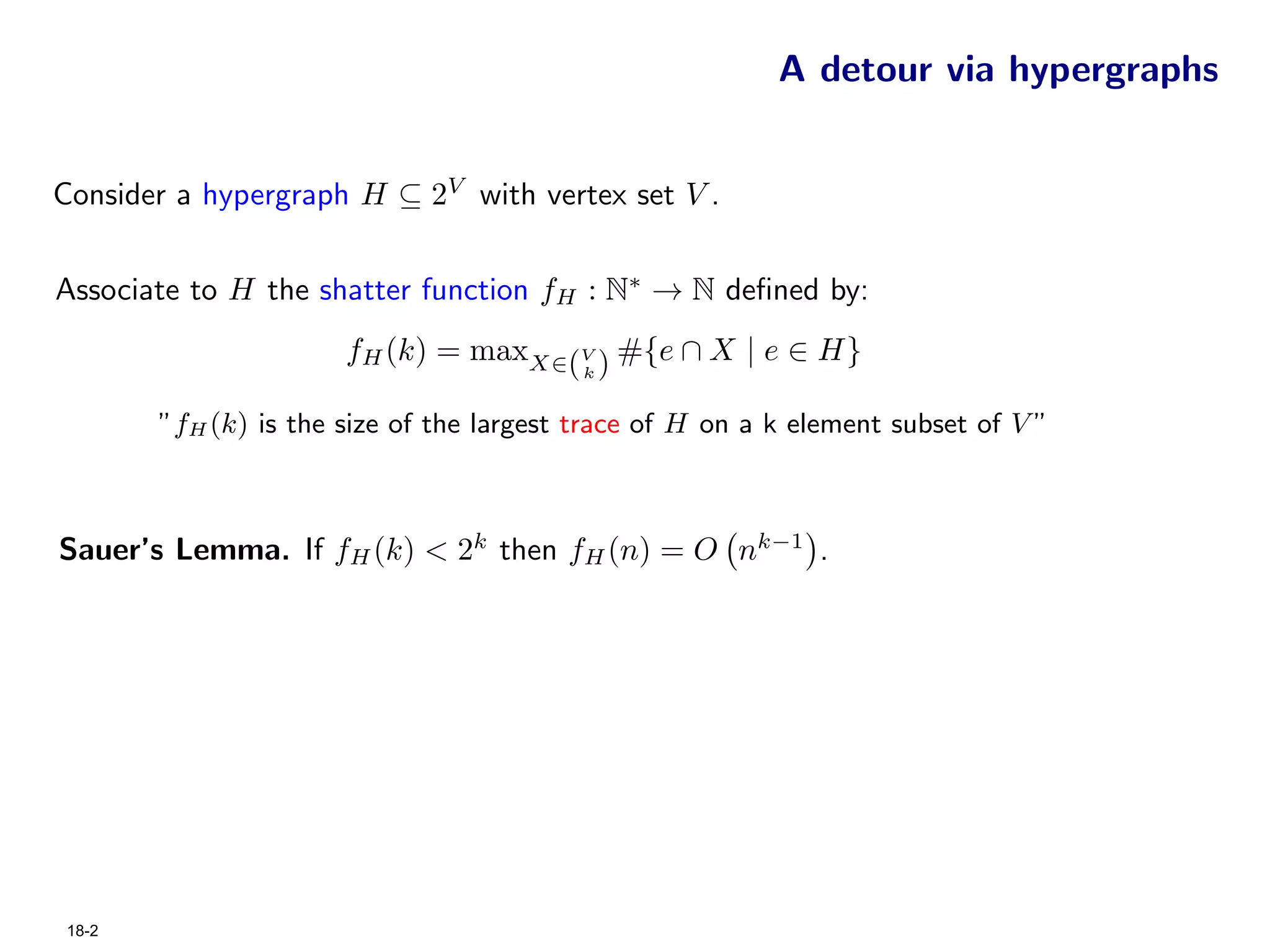

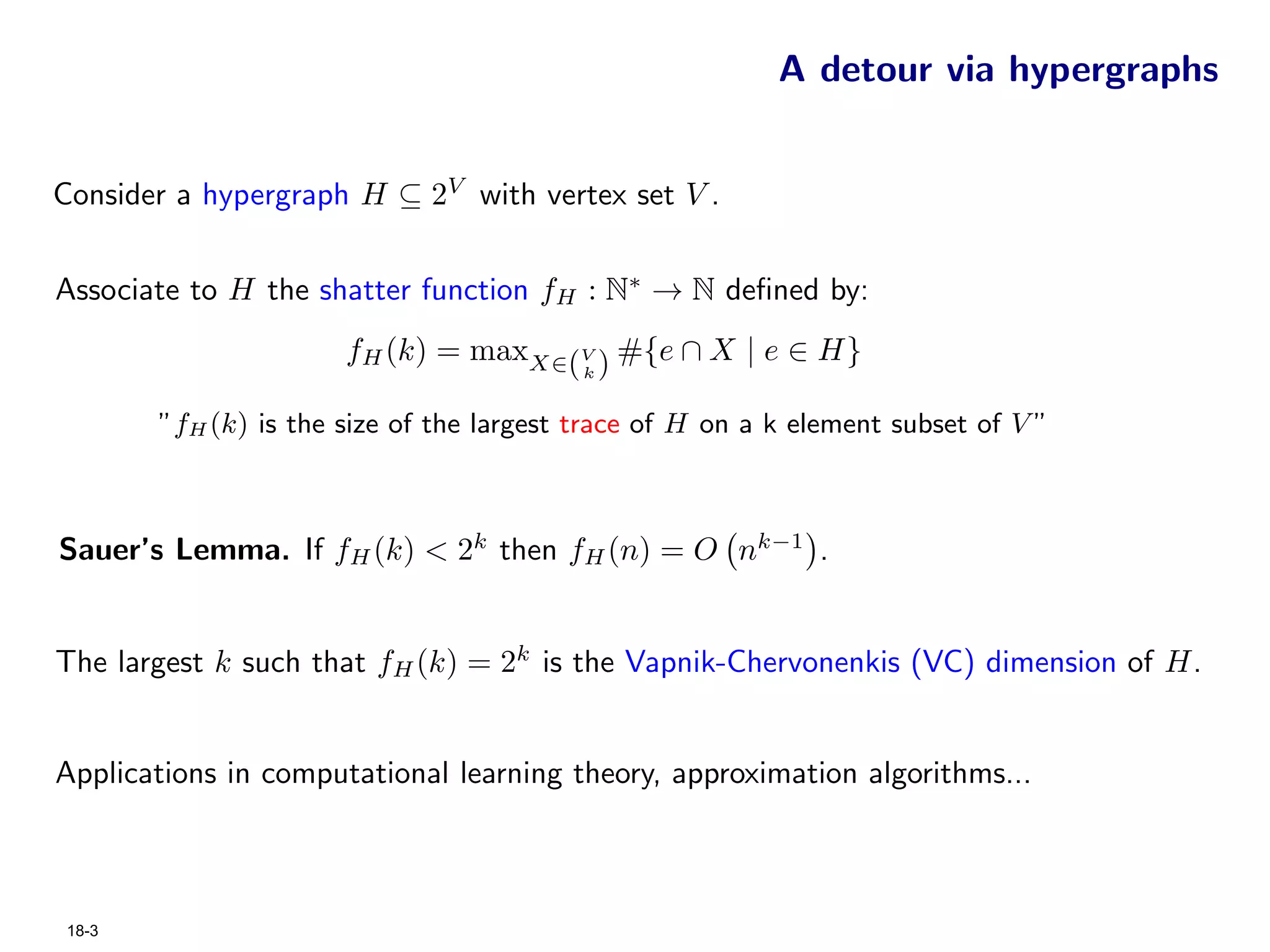

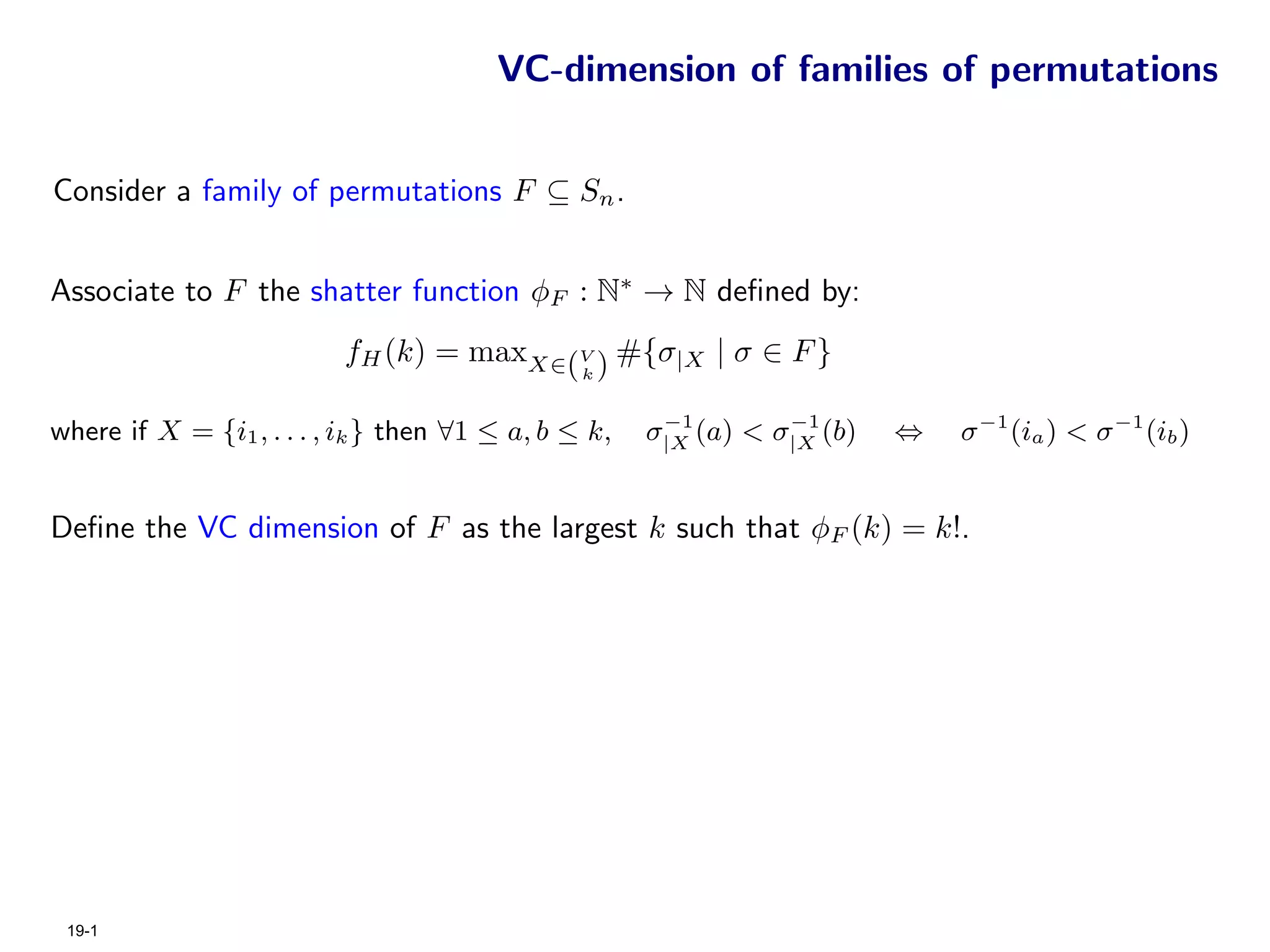

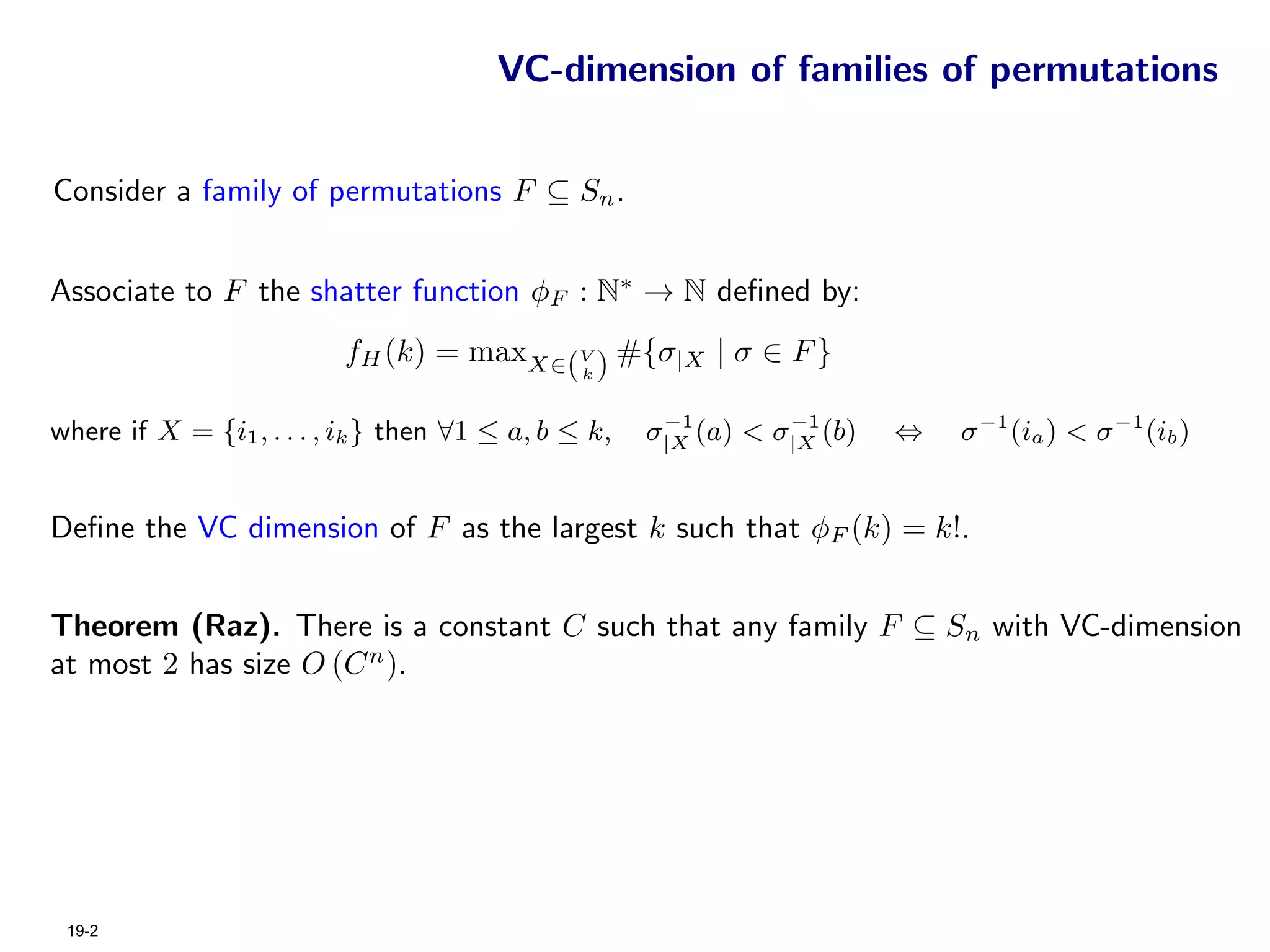

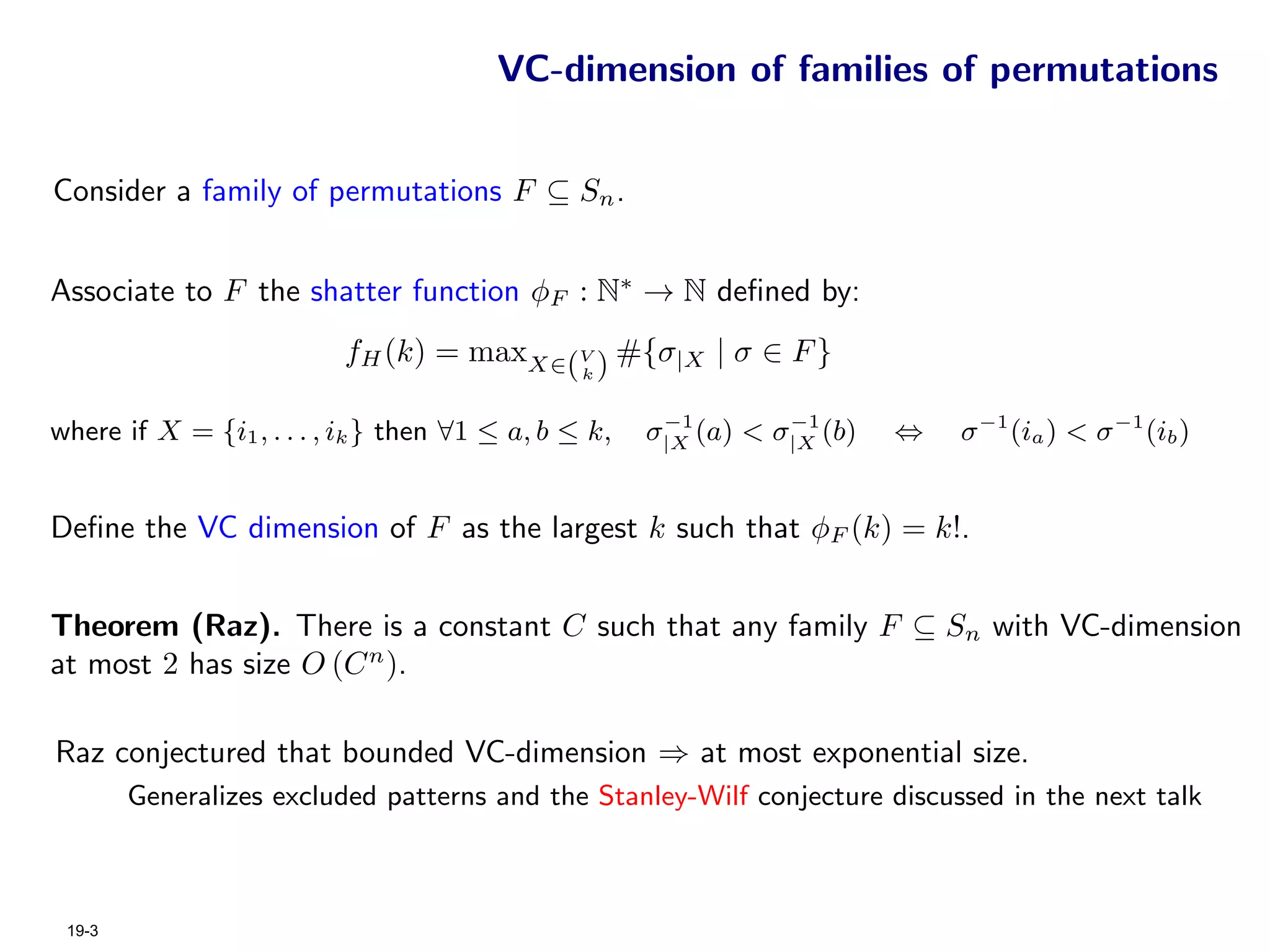

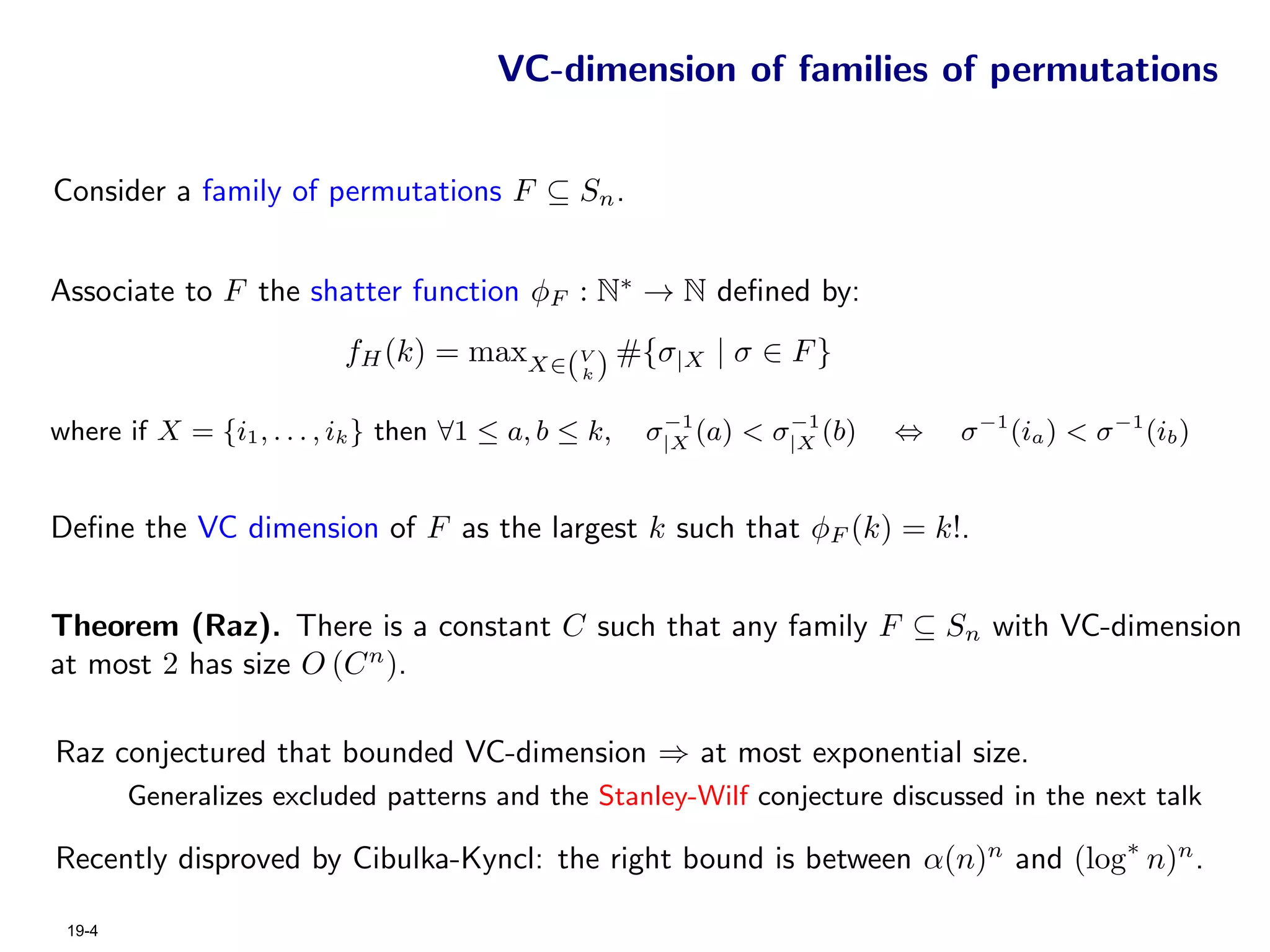

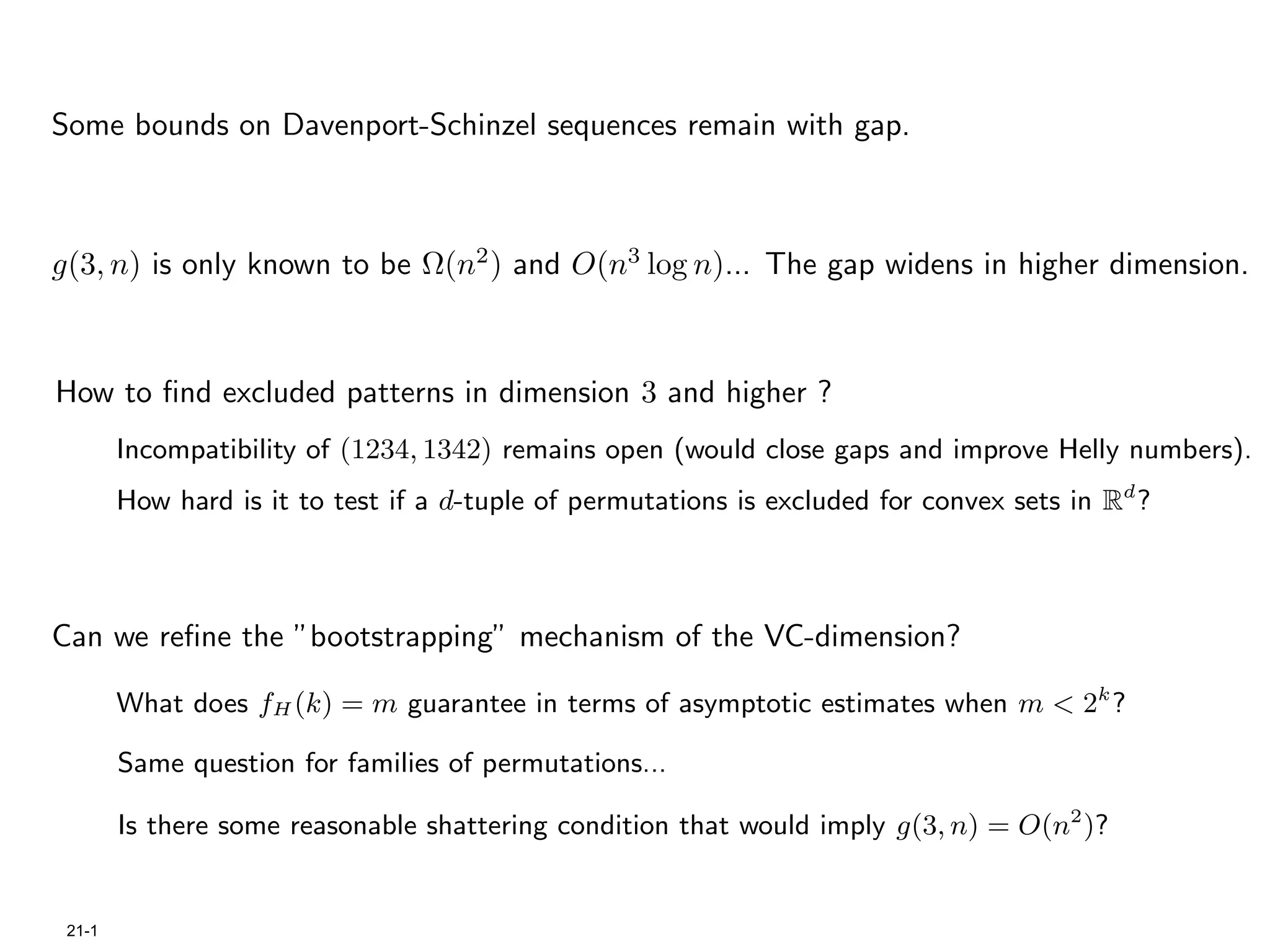

The document focuses on geometric permutations and structures associated with combinatorial and geometric objects, including the convex hull, Delaunay triangulation, and minimum spanning tree. It discusses the complexity of these geometric structures in terms of counting arguments and worst-case scenarios, alongside the introduction of geometric permutations related to convex sets. Additionally, the text explores the implications of excluded patterns in geometric permutations and their applications in algorithmic contexts.