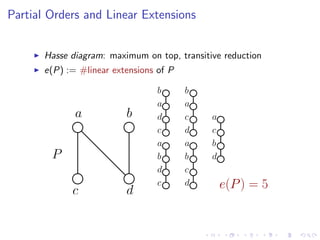

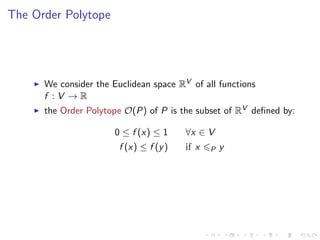

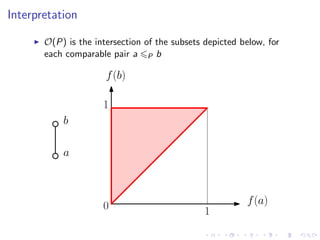

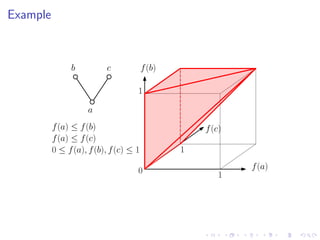

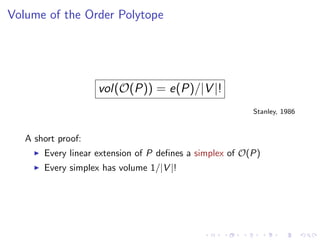

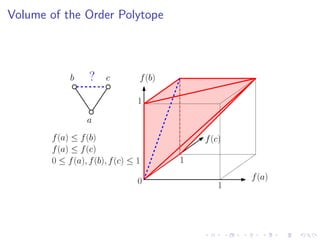

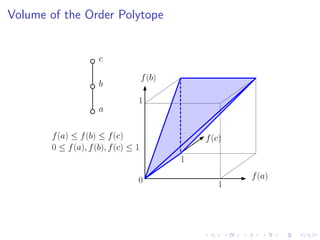

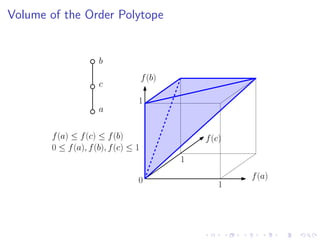

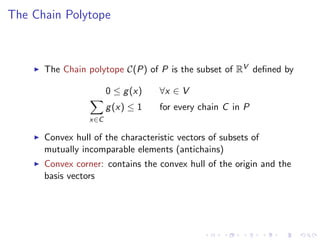

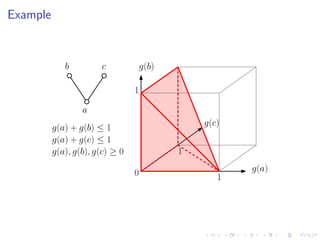

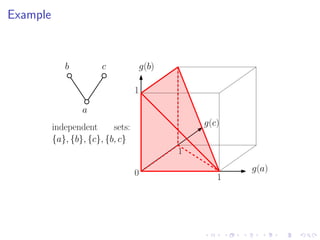

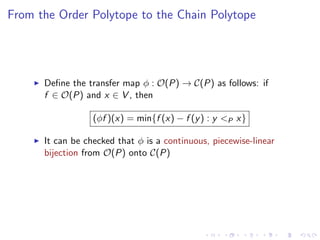

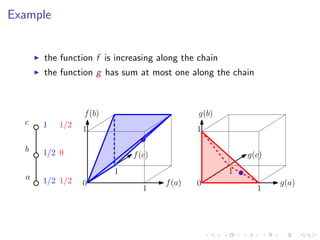

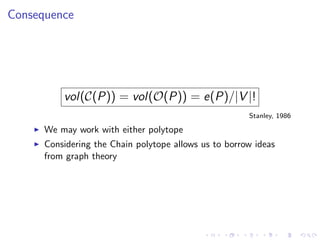

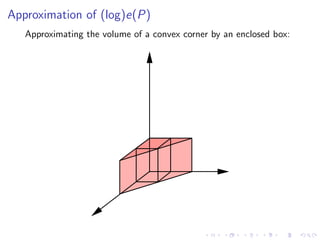

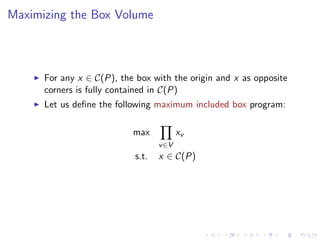

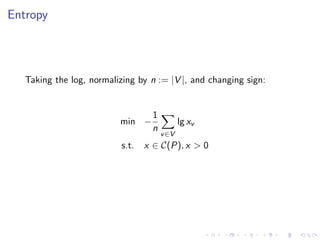

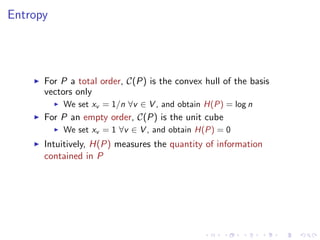

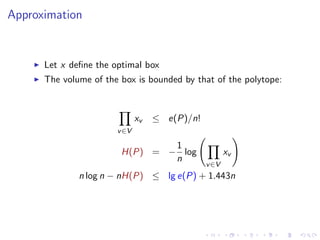

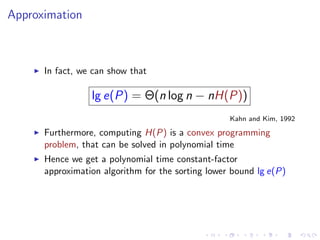

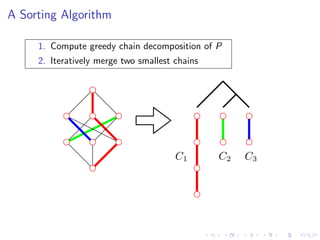

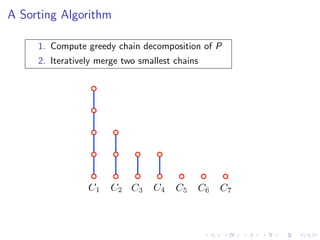

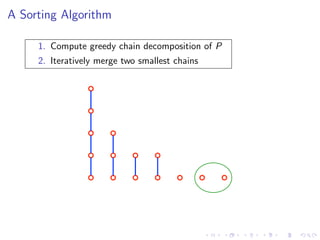

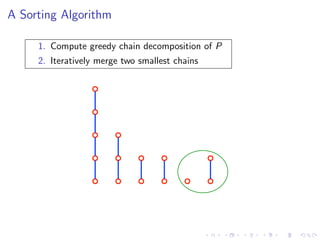

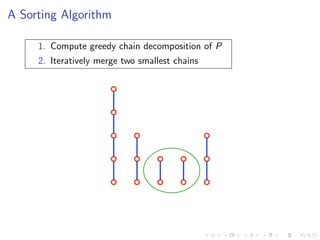

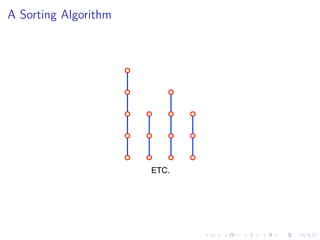

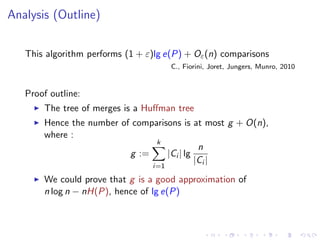

The document discusses sorting algorithms based on comparisons in the context of partial information, specifically focusing on the concept of linear extensions of partial orders. It explores the relationship between the order polytope and chain polytope, proposing an approximation method for calculating the volume of these polytopes which aids in efficient sorting algorithm development. Key findings include the establishment of a framework for approximating the number of linear extensions of a partial order, indicating potential applications in various fields.