This document contains a chapter outline and answers to questions about physics and measurement. The chapter outline lists topics like standards of length, mass and time, matter and model-building, density and atomic mass, and dimensional analysis. The answers to questions section provides explanations and calculations in response to questions about these topics. For example, it explains that atomic clocks are based on electromagnetic waves emitted by atoms, and that density varies with temperature and pressure.

![Chapter 1 15

*P1.57 Consider one cubic meter of gold. Its mass from Table 1.5 is 19 300 kg. One atom of gold has mass

m0

27

25

197 3 27 10

=

×

F

HG

I

KJ = ×

−

−

u

1.66 10 kg

1 u

kg

a f . .

So, the number of atoms in the cube is

N =

×

= ×

−

19 300

5 90 10

25

28

kg

3.27 10 kg

. .

The imagined cubical volume of each atom is

d3

28

29

1

5 90 10

1 69 10

=

×

= × −

m

m

3

3

.

. .

So

d = × −

2 57 10 10

. m .

P1.58 A N A

V

V

A

V

r

r

total drop

total

drop

drop

total

4

= =

F

HG

I

KJ =

F

H

GG

I

K

JJ

a fe j e j e j

π

π

3

3

2

4

A

V

r

total

total

3

2

m

m

m

=

F

HG I

KJ =

×

×

F

HG

I

KJ =

−

−

3

3

30 0 10

2 00 10

4 50

6

5

.

.

.

P1.59 One month is

1 30 24 3 600 2 592 106

mo day h day s h s

= = ×

b gb gb g . .

Applying units to the equation,

V t t

= +

1 50 0 008 00 2

. .

Mft mo Mft mo

3 3 2

e j e j .

Since 1 106

Mft ft

3 3

= ,

V t t

= × + ×

1 50 10 0 008 00 10

6 6 2

. .

ft mo ft mo

3 3 2

e j e j .

Converting months to seconds,

V t t

=

×

×

+

×

×

1 50 10 0 008 00 10

6 6

2

2

. .

ft mo

2.592 10 s mo

ft mo

2.592 10 s mo

3

6

3 2

6

e j

.

Thus, V t t

ft ft s ft s

3 3 3 2

[ ] . .

= + × −

0 579 1 19 10 9 2

e j e j .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/12-solutionsserwayphysics6thedition-230806185121-ebd4e979/85/1-2-Solutions-Serway-Physics-6Th-Edition-15-320.jpg)

![70 Vectors

Additional Problems

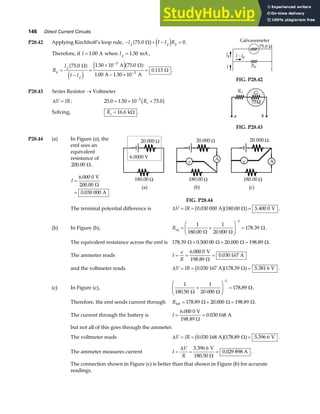

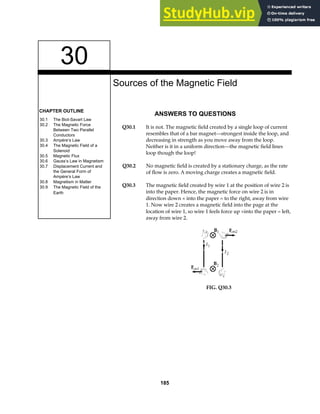

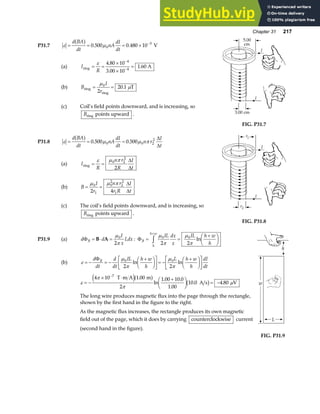

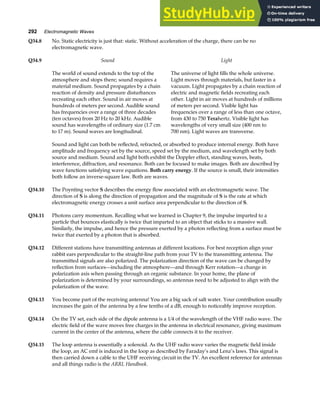

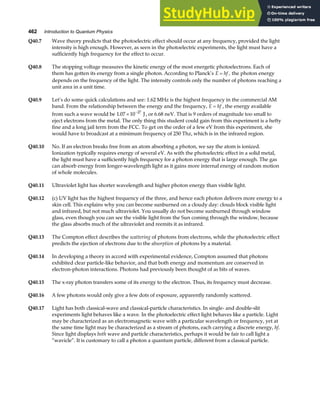

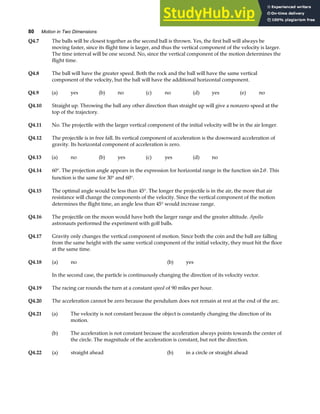

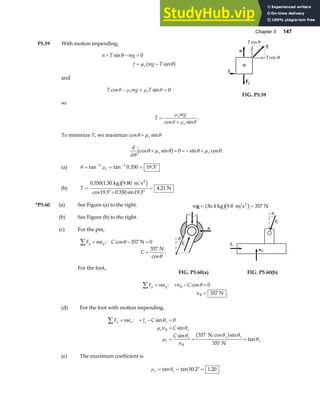

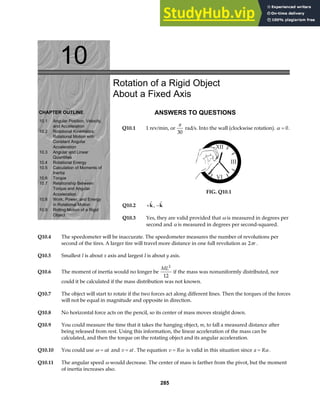

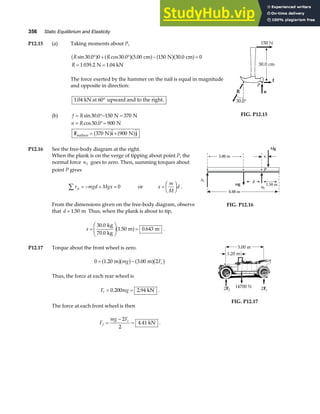

P3.51 Let θ represent the angle between the directions of A and B. Since

A and B have the same magnitudes, A, B, and R A B

= + form an

isosceles triangle in which the angles are 180°−θ ,

θ

2

, and

θ

2

. The

magnitude of R is then R A

=

F

HG I

KJ

2

2

cos

θ

. [Hint: apply the law of

cosines to the isosceles triangle and use the fact that B A

= .]

Again, A, –B, and D A B

= − form an isosceles triangle with apex

angle θ. Applying the law of cosines and the identity

1 2

2

2

− =

F

HG I

KJ

cos sin

θ

θ

a f

gives the magnitude of D as D A

=

F

HG I

KJ

2

2

sin

θ

.

The problem requires that R D

=100 .

Thus, 2

2

200

2

A A

cos sin

θ θ

F

HG I

KJ =

F

HG I

KJ. This gives tan .

θ

2

0 010

F

HG I

KJ = and

θ = °

1 15

. .

A

B

R

θ/2

θ

A

D –B

θ

FIG. P3.51

P3.52 Let θ represent the angle between the directions of A and B. Since

A and B have the same magnitudes, A, B, and R A B

= + form an

isosceles triangle in which the angles are 180°−θ ,

θ

2

, and

θ

2

. The

magnitude of R is then R A

=

F

HG I

KJ

2

2

cos

θ

. [Hint: apply the law of

cosines to the isosceles triangle and use the fact that B A

= . ]

Again, A, –B, and D A B

= − form an isosceles triangle with apex

angle θ. Applying the law of cosines and the identity

1 2

2

2

− =

F

HG I

KJ

cos sin

θ

θ

a f

gives the magnitude of D as D A

=

F

HG I

KJ

2

2

sin

θ

.

The problem requires that R nD

= or cos sin

θ θ

2 2

F

HG I

KJ =

F

HG I

KJ

n giving

θ =

F

HG I

KJ

−

2

1

1

tan

n

.

FIG. P3.52](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/12-solutionsserwayphysics6thedition-230806185121-ebd4e979/85/1-2-Solutions-Serway-Physics-6Th-Edition-69-320.jpg)

![76 Vectors

P3.65 Since

A B j

+ = 6 00

. ,

we have

A B A B

x x y y

+ + + = +

b g e j

.

i j i j

0 6 00

giving

FIG. P3.65

A B

x x

+ = 0 or A B

x x

=− [1]

and

A B

y y

+ = 6 00

. . [2]

Since both vectors have a magnitude of 5.00, we also have

A A B B

x y x y

2 2 2 2 2

5 00

+ = + = . .

From A B

x x

=− , it is seen that

A B

x x

2 2

= .

Therefore, A A B B

x y x y

2 2 2 2

+ = + gives

A B

y y

2 2

= .

Then, A B

y y

= and Eq. [2] gives

A B

y y

= = 3 00

. .

Defining θ as the angle between either A or B and the y axis, it is seen that

cos

.

.

.

θ = = = =

A

A

B

B

y y 3 00

5 00

0 600 and θ = °

53 1

. .

The angle between A and B is then φ θ

= = °

2 106 .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/12-solutionsserwayphysics6thedition-230806185121-ebd4e979/85/1-2-Solutions-Serway-Physics-6Th-Edition-75-320.jpg)

![Chapter 4 93

P4.24 From the instant he leaves the floor until just before he lands, the basketball star is a projectile. His

vertical velocity and vertical displacement are related by the equation v v a y y

yf yi y f i

2 2

2

= + −

d i.

Applying this to the upward part of his flight gives 0 2 9 80 1 85 1 02

2

= + − −

vyi . . .

m s m

2

e ja f . From this,

vyi = 4 03

. m s. [Note that this is the answer to part (c) of this problem.]

For the downward part of the flight, the equation gives vyf

2

0 2 9 80 0 900 1 85

= + − −

. . .

m s m

2

e ja f .

Thus the vertical velocity just before he lands is

vyf = −4 32

. m s.

(a) His hang time may then be found from v v a t

yf yi y

= + :

− = + −

4 32 4 03 9 80

. . .

m s m s m s2

e jt

or t = 0 852

. s .

(b) Looking at the total horizontal displacement during the leap, x v t

xi

= becomes

2 80 0 852

. .

m s

= vxi a f

which yields vxi = 3 29

. m s .

(c) vyi = 4.03 m s . See above for proof.

(d) The takeoff angle is: θ =

F

HG

I

KJ =

F

HG

I

KJ = °

− −

tan tan

.

.

1 1 4 03

50 8

v

v

yi

xi

m s

3.29 m s

.

(e) Similarly for the deer, the upward part of the flight gives

v v a y y

yf yi y f i

2 2

2

= + −

d i:

0 2 9 80 2 50 1 20

2

= + − −

vyi . . .

m s m

2

e ja f

so vyi = 5 04

. m s.

For the downward part, v v a y y

yf yi y f i

2 2

2

= + −

d i yields vyf

2

0 2 9 80 0 700 2 50

= + − −

. . .

m s m

2

e ja f

and vyf = −5 94

. m s.

The hang time is then found as v v a t

yf yi y

= + : − = + −

5 94 5 04 9 80

. . .

m s m s m s2

e jt and

t = 1 12

. s .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/12-solutionsserwayphysics6thedition-230806185121-ebd4e979/85/1-2-Solutions-Serway-Physics-6Th-Edition-92-320.jpg)

![Chapter 18 535

P18.28 λG

G

v

f

= =

2 0 350

. m

a f ; λ A A

A

L

v

f

= =

2

L L L

f

f

L L

f

f

G A G

G

A

G G

G

A

− = −

F

HG I

KJ = −

F

HG I

KJ = −

F

HG I

KJ =

1 0 350 1

392

440

0 038 2

. .

m m

a f

Thus, L L

A G

= − = − =

0 038 2 0 350 0 038 2 0 312

. . . .

m m m m,

or the finger should be placed 31 2

. cm from the bridge .

L

v

f f

T

A

A A

= =

2

1

2 µ

; dL

dT

f T

A

A

=

4 µ

;

dL

L

dT

T

A

A

=

1

2

dT

T

dL

L

A

A

= =

−

=

2 2

0 600

3 82

3 84%

.

.

.

cm

35.0 cm

a f

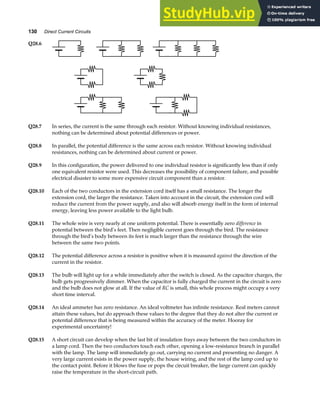

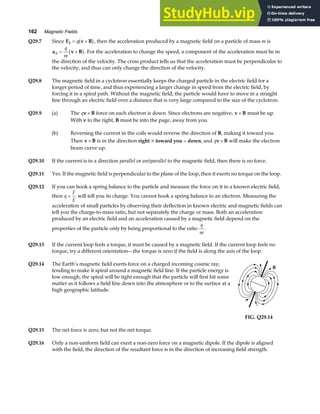

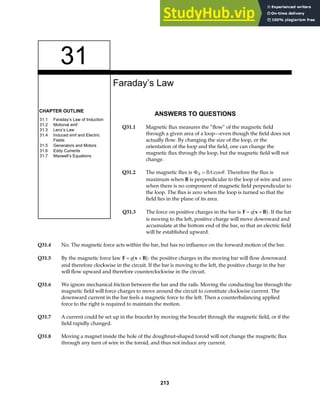

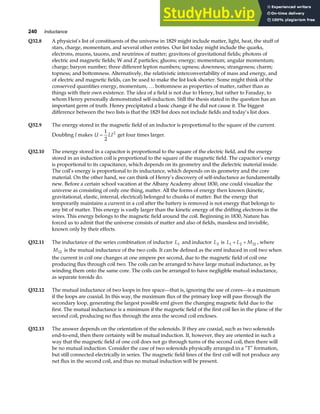

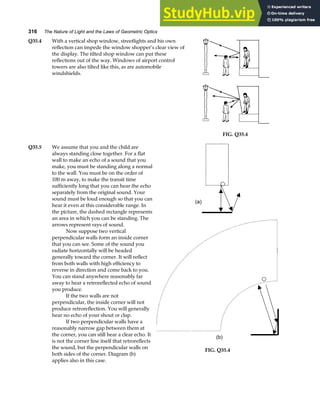

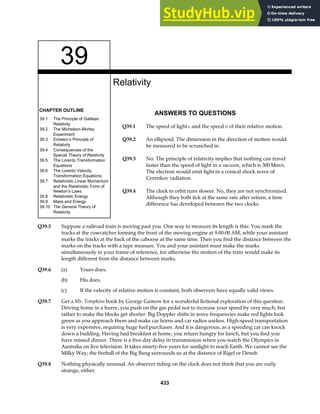

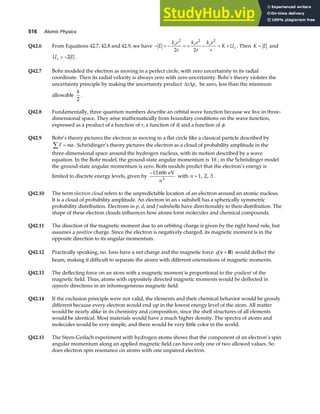

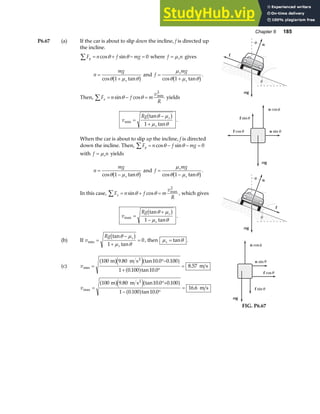

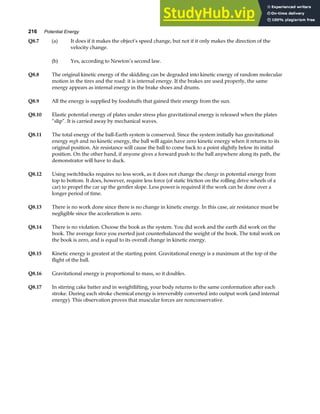

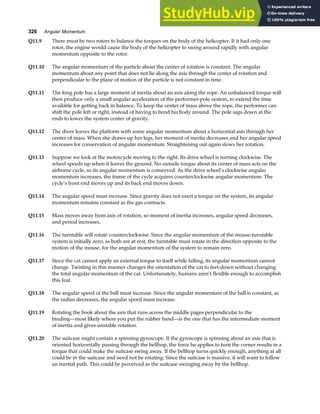

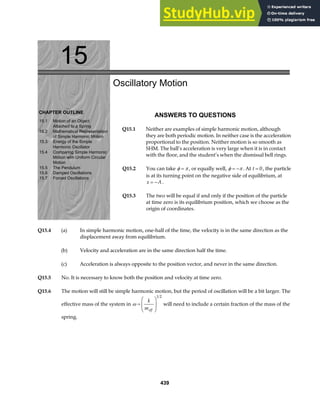

P18.29 In the fundamental mode, the string above the rod has only

two nodes, at A and B, with an anti-node halfway between A

and B. Thus,

λ

θ

2

= =

AB

L

cos

or λ

θ

=

2L

cos

.

Since the fundamental frequency is f, the wave speed in this

segment of string is

v f

Lf

= =

λ

θ

2

cos

.

Also, v

T T

m AB

TL

m

= = =

µ θ

cos

where T is the tension in this part of the string. Thus,

2Lf TL

m

cos cos

θ θ

= or

4 2 2

2

L f TL

m

cos cos

θ θ

=

and the mass of string above the rod is:

m

T

Lf

=

cosθ

4 2

[Equation 1]

L

M

θ

A

B

T

F

Mg

θ

FIG. P18.29

Now, consider the tension in the string. The light rod would rotate about point P if the string exerted

any vertical force on it. Therefore, recalling Newton’s third law, the rod must exert only a horizontal

force on the string. Consider a free-body diagram of the string segment in contact with the end of

the rod.

F T Mg T

Mg

y

∑ = − = ⇒ =

sin

sin

θ

θ

0

Then, from Equation 1, the mass of string above the rod is

m

Mg

Lf

Mg

Lf

=

F

HG I

KJ =

sin

cos

tan

θ

θ

θ

4 4

2 2

.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/12-solutionsserwayphysics6thedition-230806185121-ebd4e979/85/1-2-Solutions-Serway-Physics-6Th-Edition-533-320.jpg)

![Chapter 20 583

P20.17 The bullet will not melt all the ice, so its final temperature is 0°C.

Then

1

2

2

mv mc T m L

w f

+

F

HG I

KJ =

∆

bullet

where mw is the melt water mass

m

m

w

w

=

× + × ⋅° °

×

=

+

=

− −

0 500 3 00 10 240 3 00 10 30 0

3 33 10

86 4 11 5

0 294

3 2 3

5

. . . .

.

. .

.

kg m s kg 128 J kg C C

J kg

J J

333 000 J kg

g

e jb g b ga f

P20.18 (a) Q1 = heat to melt all the ice = × × = ×

−

50 0 10 3 33 10 1 67 10

3 5 4

. . .

kg J kg J

e je j

Q2

3 4

50 0 10 4186 100 2 09 10

= °

= × ⋅° ° = ×

−

heat to raise temp of ice to 100 C

kg J kg C C J

b g

e jb ga f

. .

Thus, the total heat to melt ice and raise temp to 100°C = ×

3 76 104

. J

Q3

3 6 4

10 0 10 2 26 10 2 26 10

= = × × = ×

−

heat available

as steam condenses

kg J kg J

. . .

e je j

Thus, we see that Q Q

3 1

, but Q Q Q

3 1 2

+ .

Therefore, all the ice melts but Tf °

100 C. Let us now find Tf

Q Q

T

T

f

f

cold hot

kg J kg kg J kg C C

kg J kg kg J kg C C

= −

× × + × ⋅° − °

= − × − × − × ⋅° − °

− −

− −

50 0 10 3 33 10 50 0 10 4186 0

10 0 10 2 26 10 10 0 10 4 186 100

3 5 3

3 6 3

. . .

. . .

e je j e jb gd i

e je j e jb gd i

From which, Tf = °

40 4

. C .

(b) Q1 = heat to melt all ice = ×

1 67 104

. J [See part (a)]

Q

Q

2

3 6 3

3

3

10 2 26 10 2 26 10

10 4 186 100 419

= = × = ×

=

°

= ⋅° ° =

−

−

heat given up

as steam condenses

kg J kg J

heat given up as condensed

steam cools to 0 C

kg J kg C C J

e je j

e jb ga f

. .

Note that Q Q Q

2 3 1

+ . Therefore, the final temperature will be 0°C with some ice

remaining. Let us find the mass of ice which must melt to condense the steam and cool the

condensate to 0°C.

mL Q Q

f = + = ×

2 3

3

2 68 10

. J

Thus, m =

×

×

= × =

−

2 68 10

8 04 10 8 04

3

3

.

. .

J

3.33 10 J kg

kg g

5

.

Therefore, there is 42 0

. g of ice left over .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/12-solutionsserwayphysics6thedition-230806185121-ebd4e979/85/1-2-Solutions-Serway-Physics-6Th-Edition-581-320.jpg)