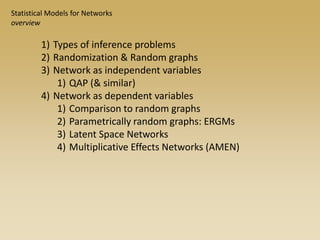

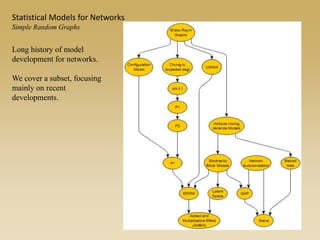

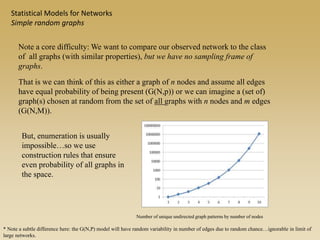

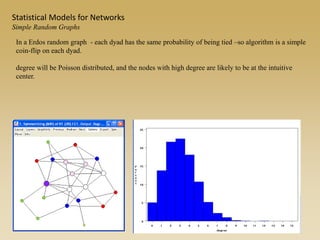

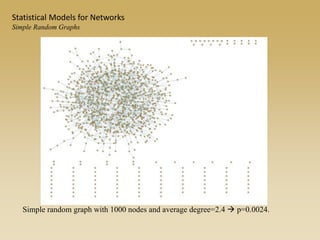

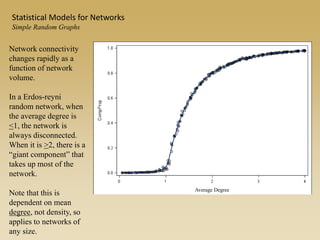

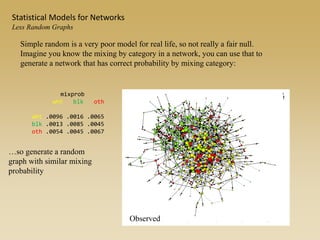

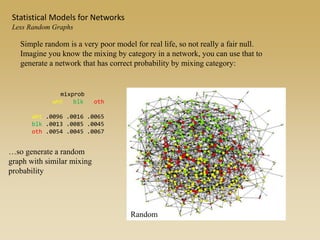

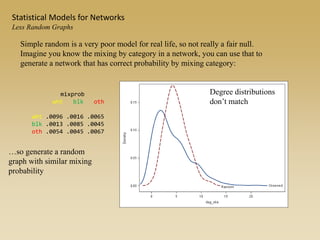

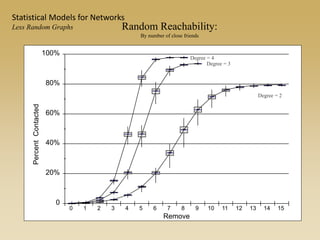

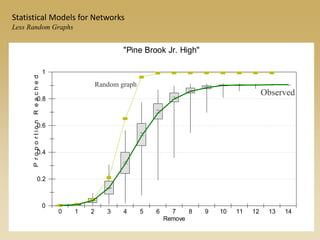

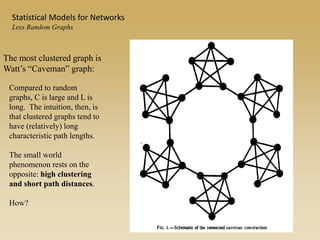

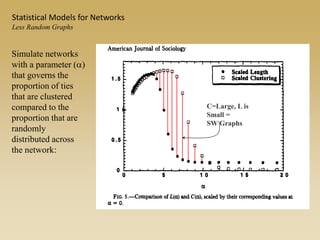

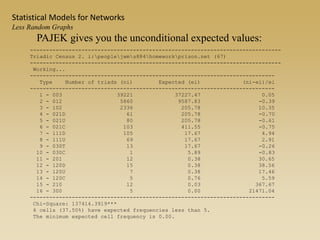

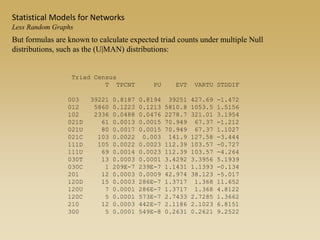

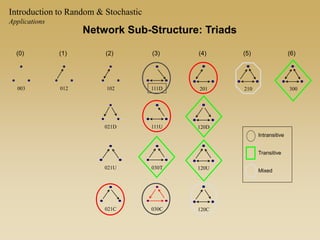

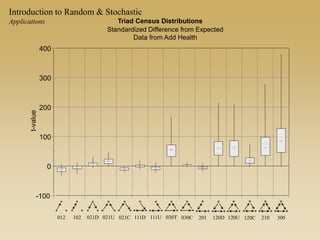

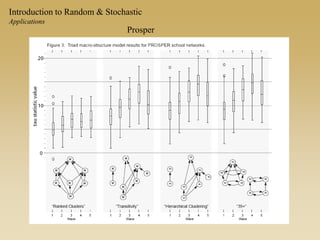

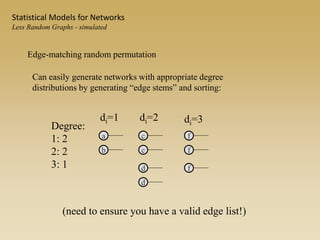

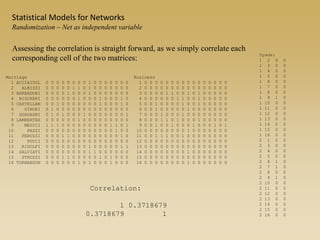

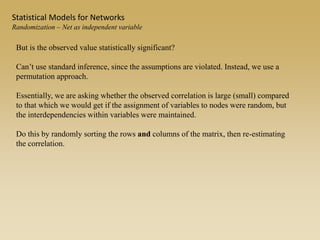

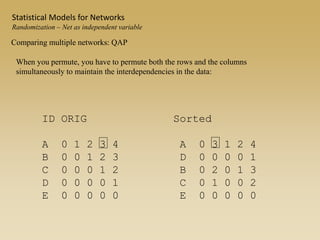

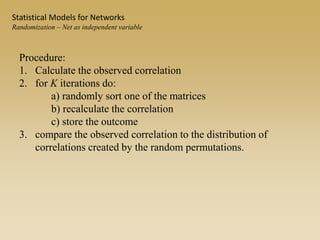

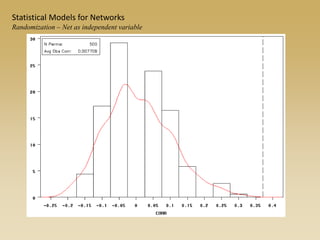

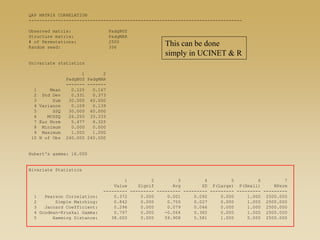

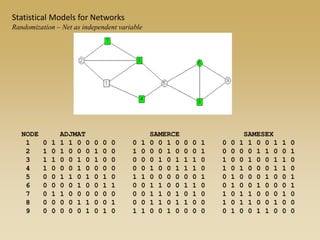

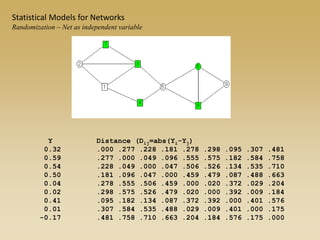

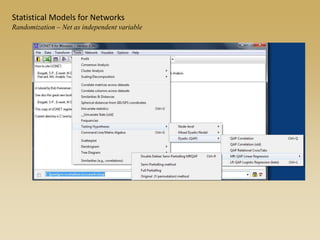

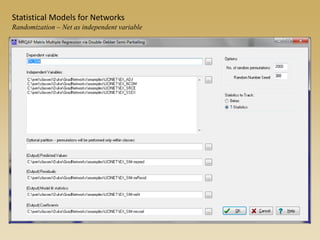

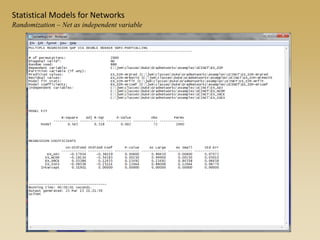

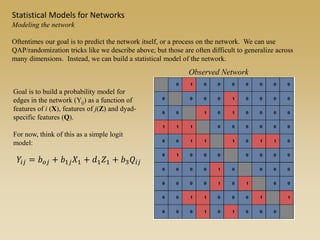

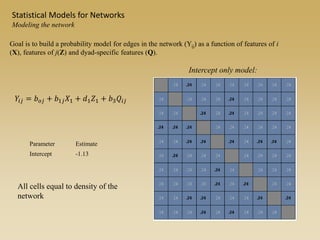

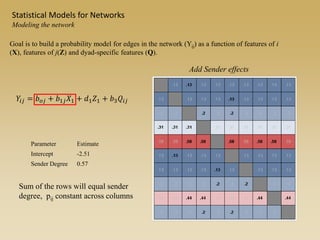

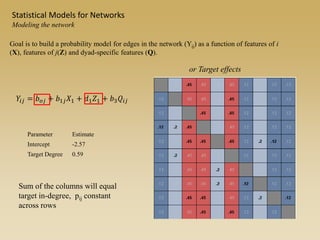

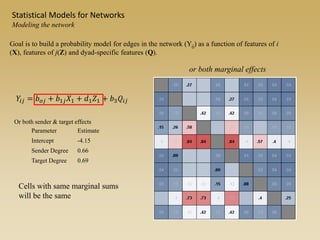

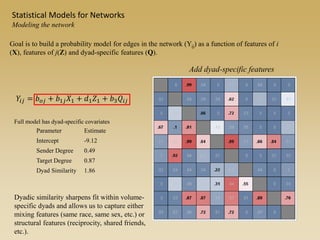

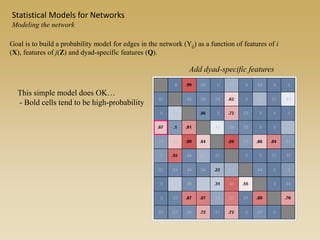

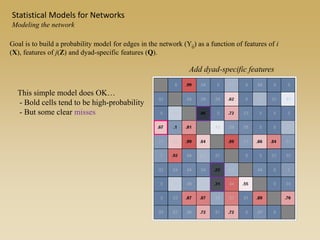

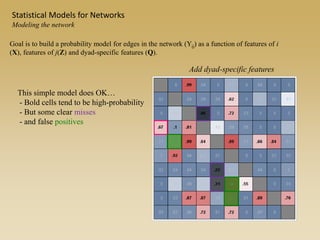

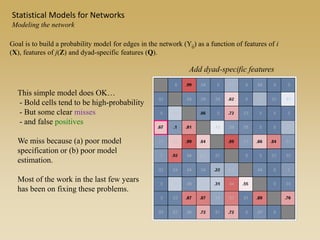

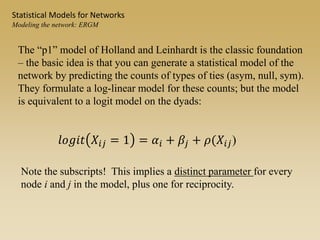

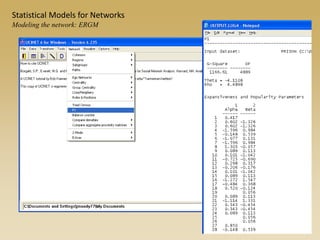

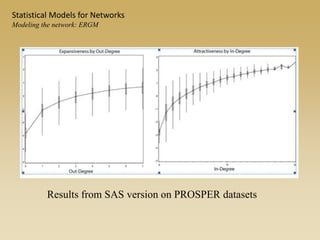

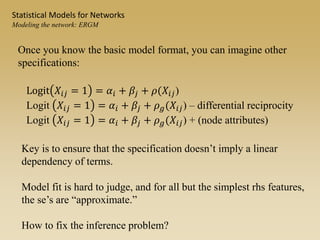

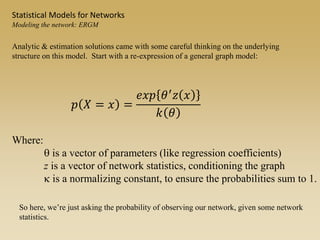

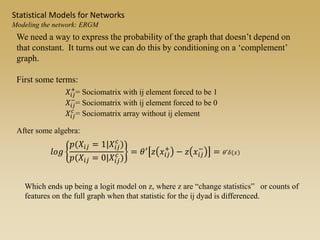

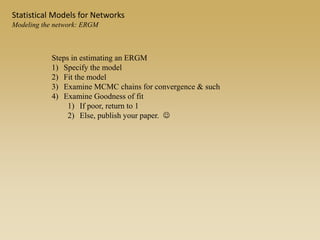

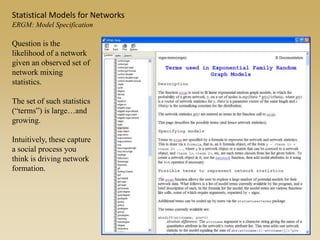

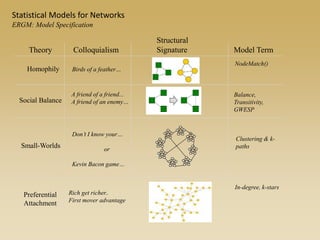

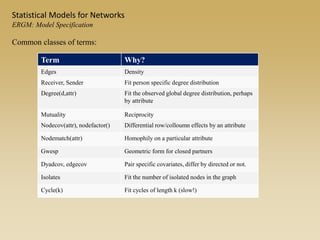

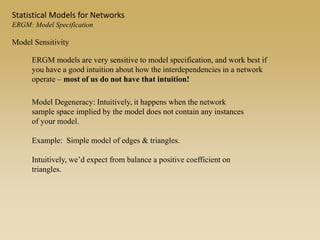

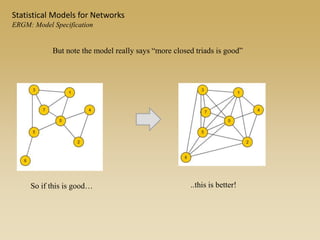

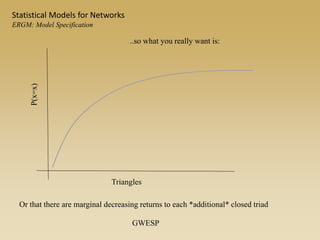

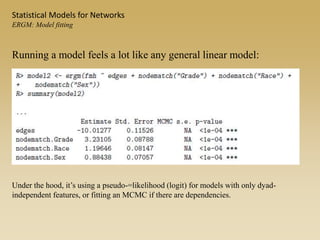

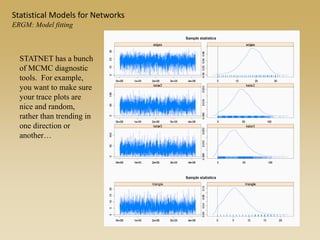

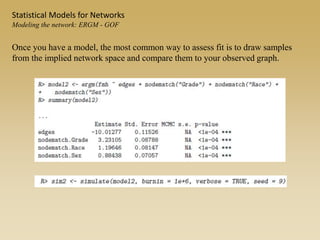

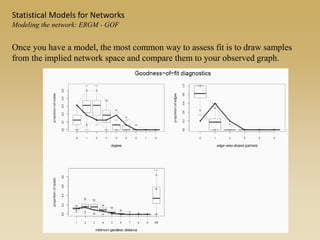

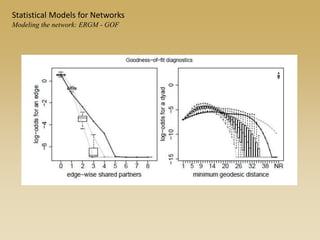

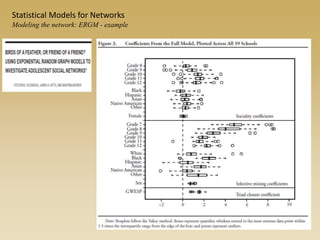

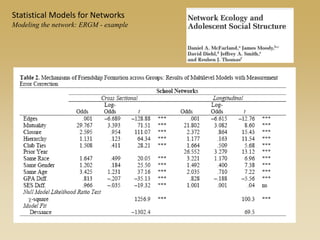

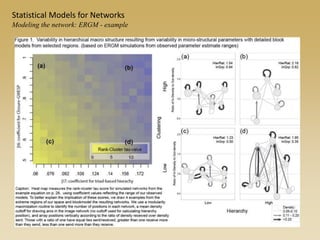

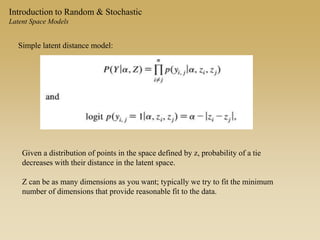

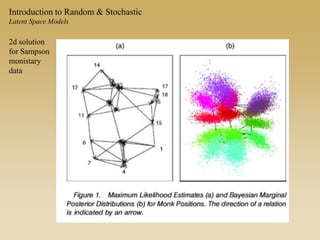

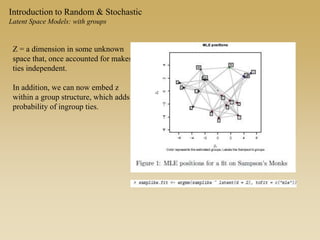

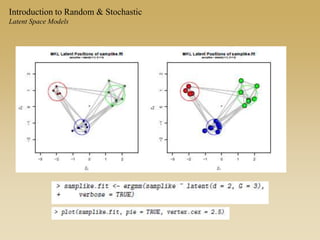

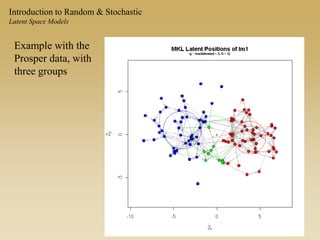

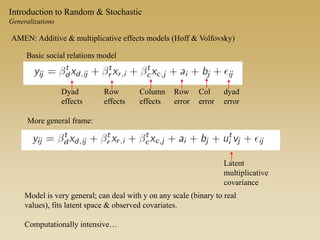

The document discusses statistical models for networks. It covers types of inference problems in networks, simple random graphs models, and less random graph models that condition on additional network features like degree distribution or mixing patterns. It also discusses comparing two networks using quadratic assignment procedures and generating networks with appropriate degree distributions for comparison.