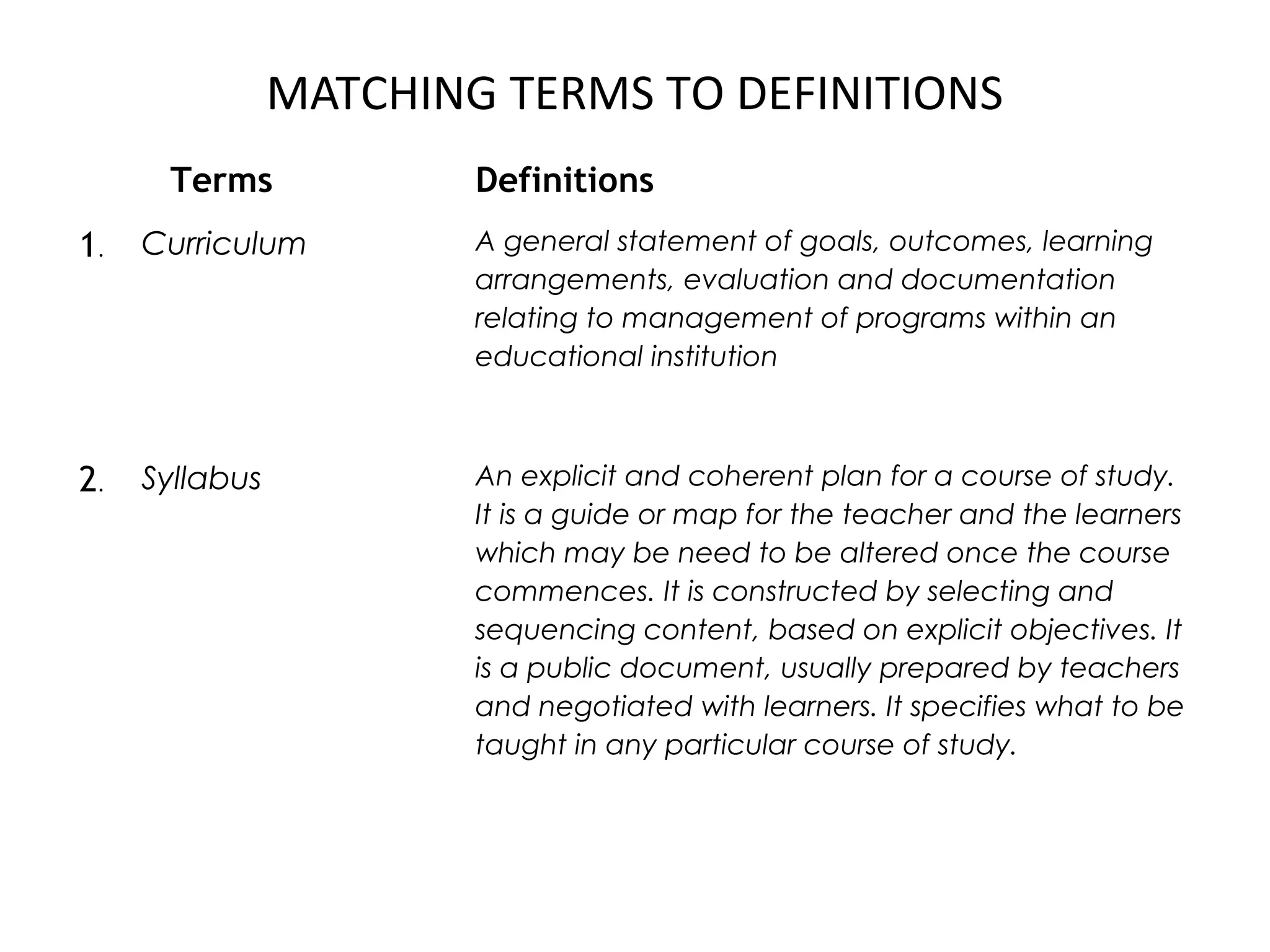

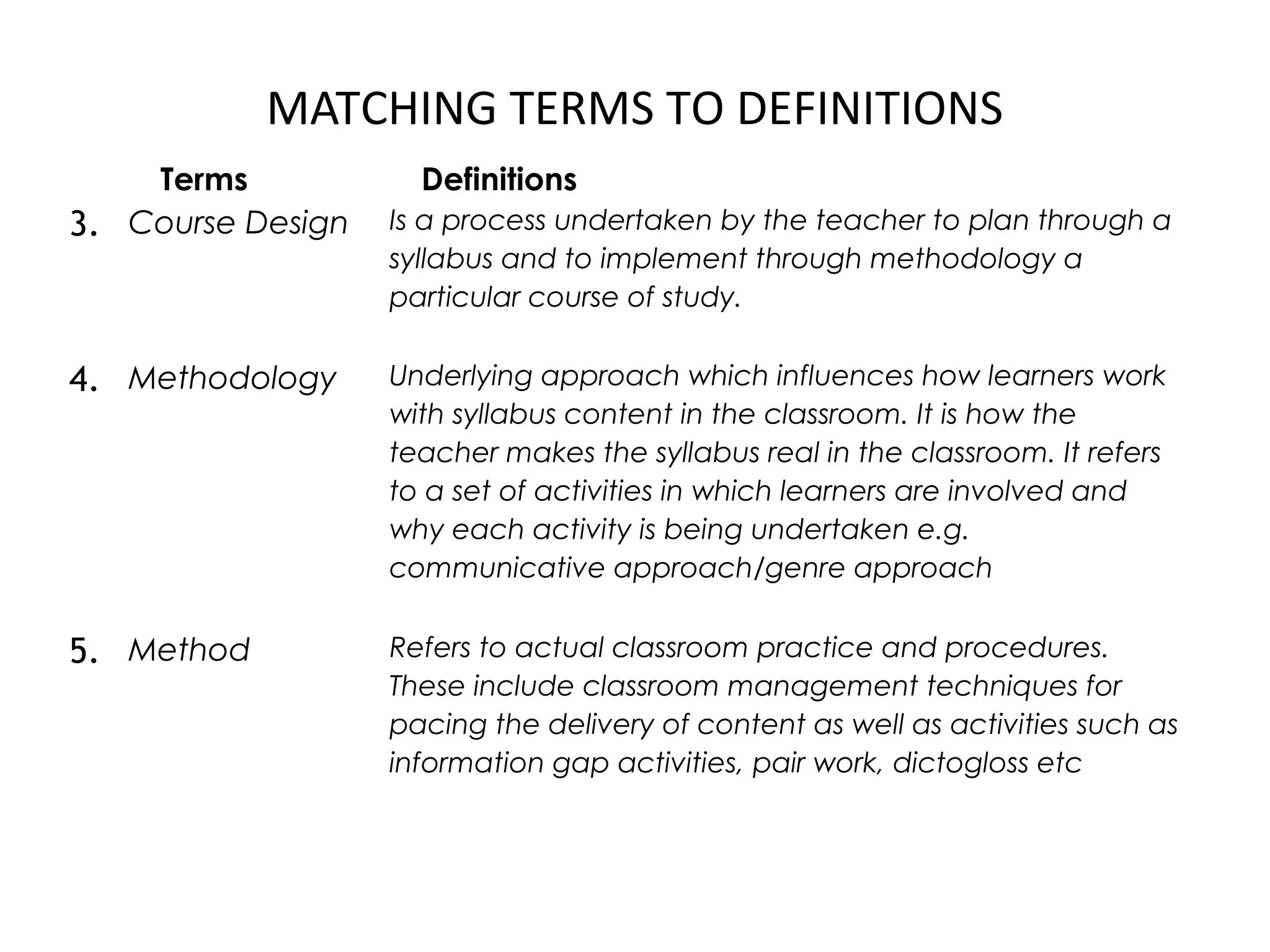

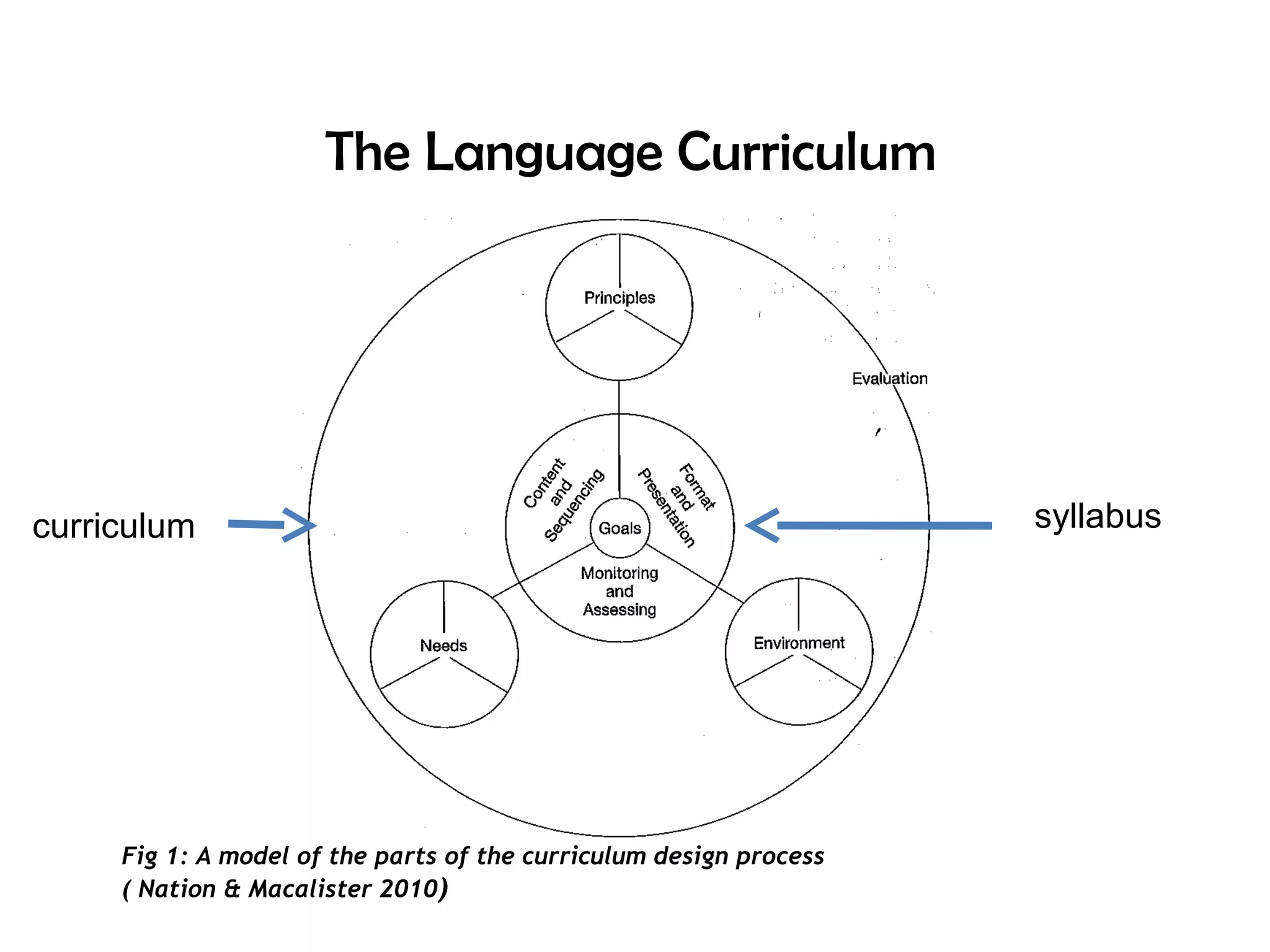

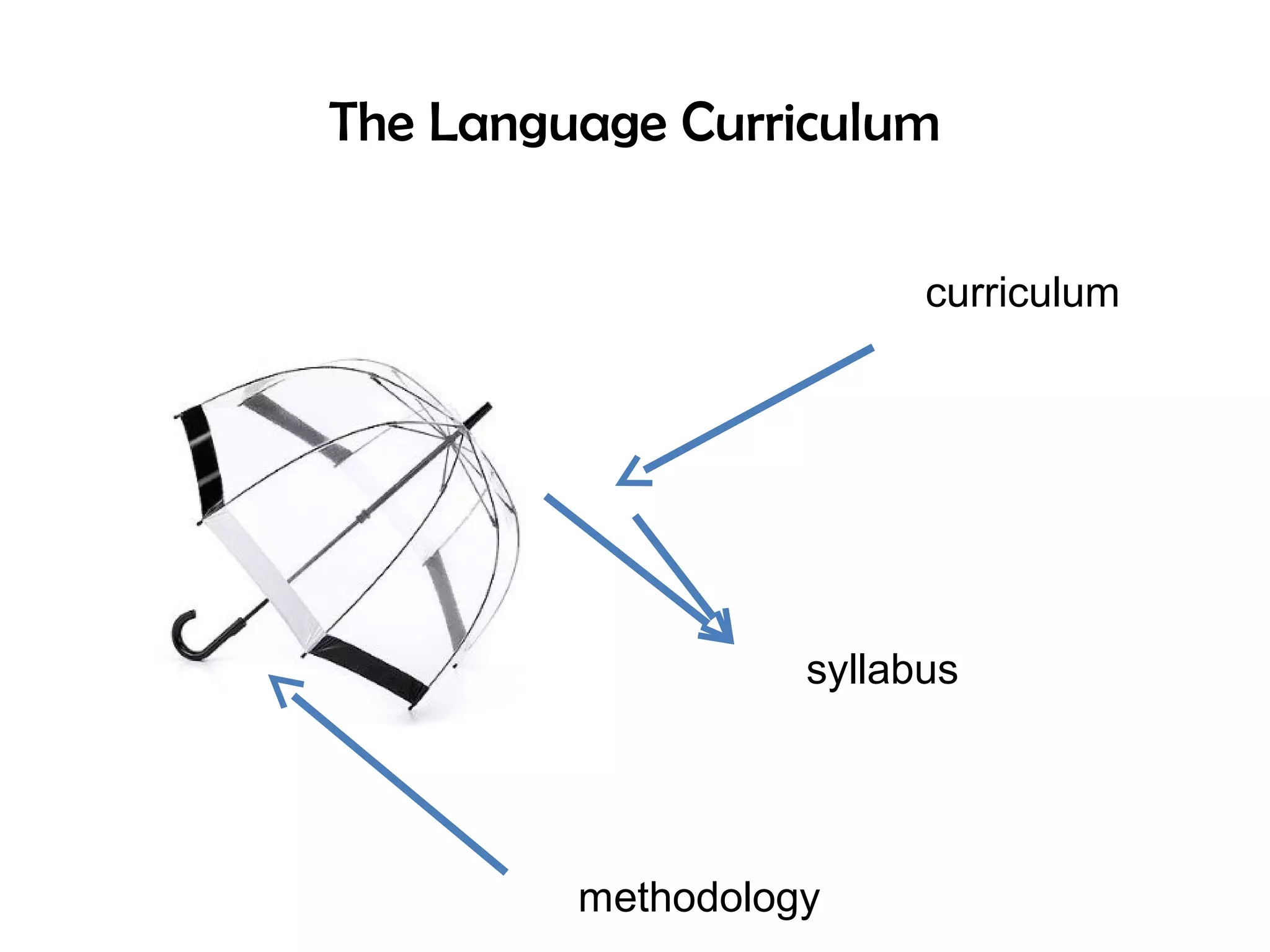

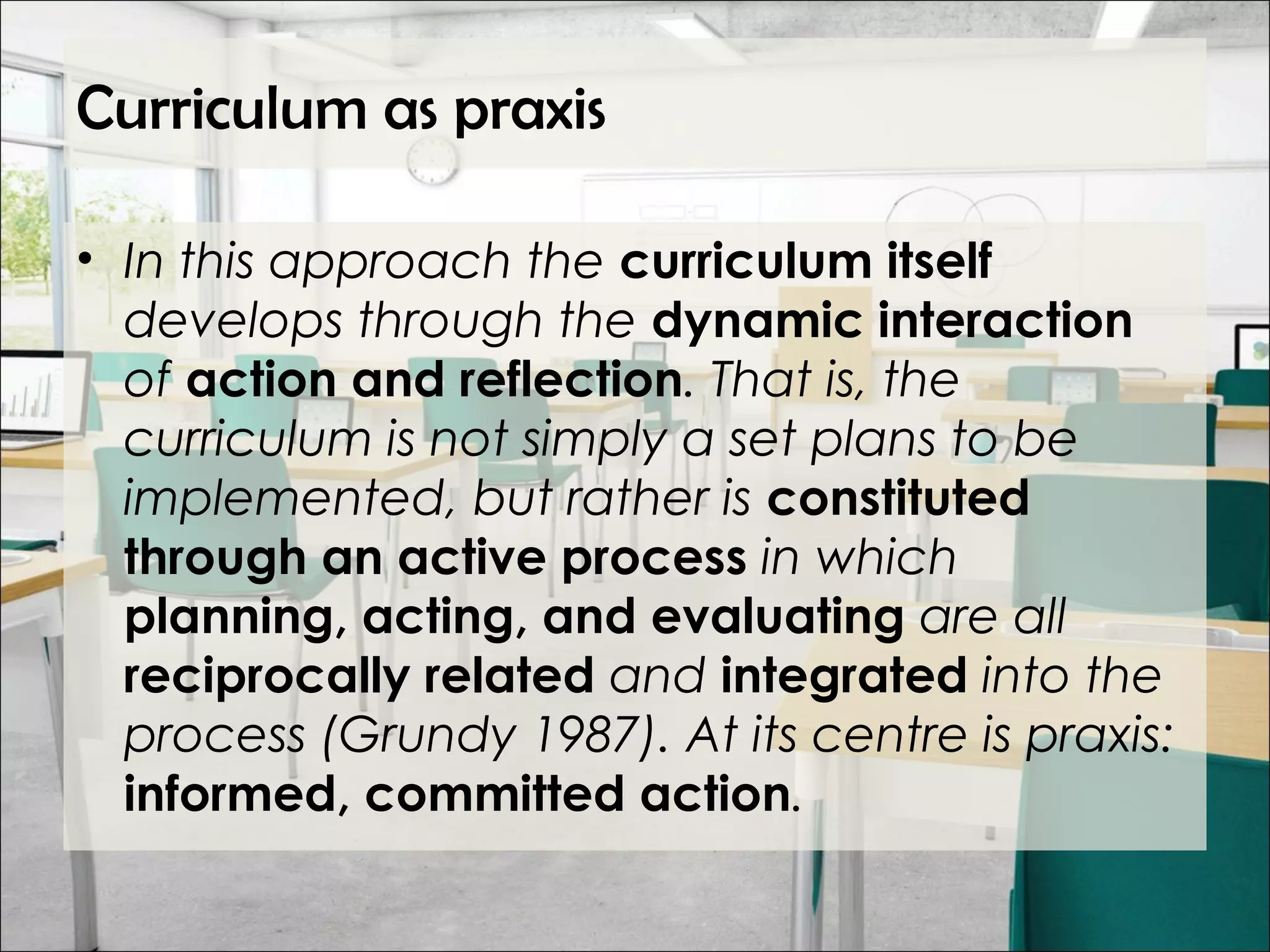

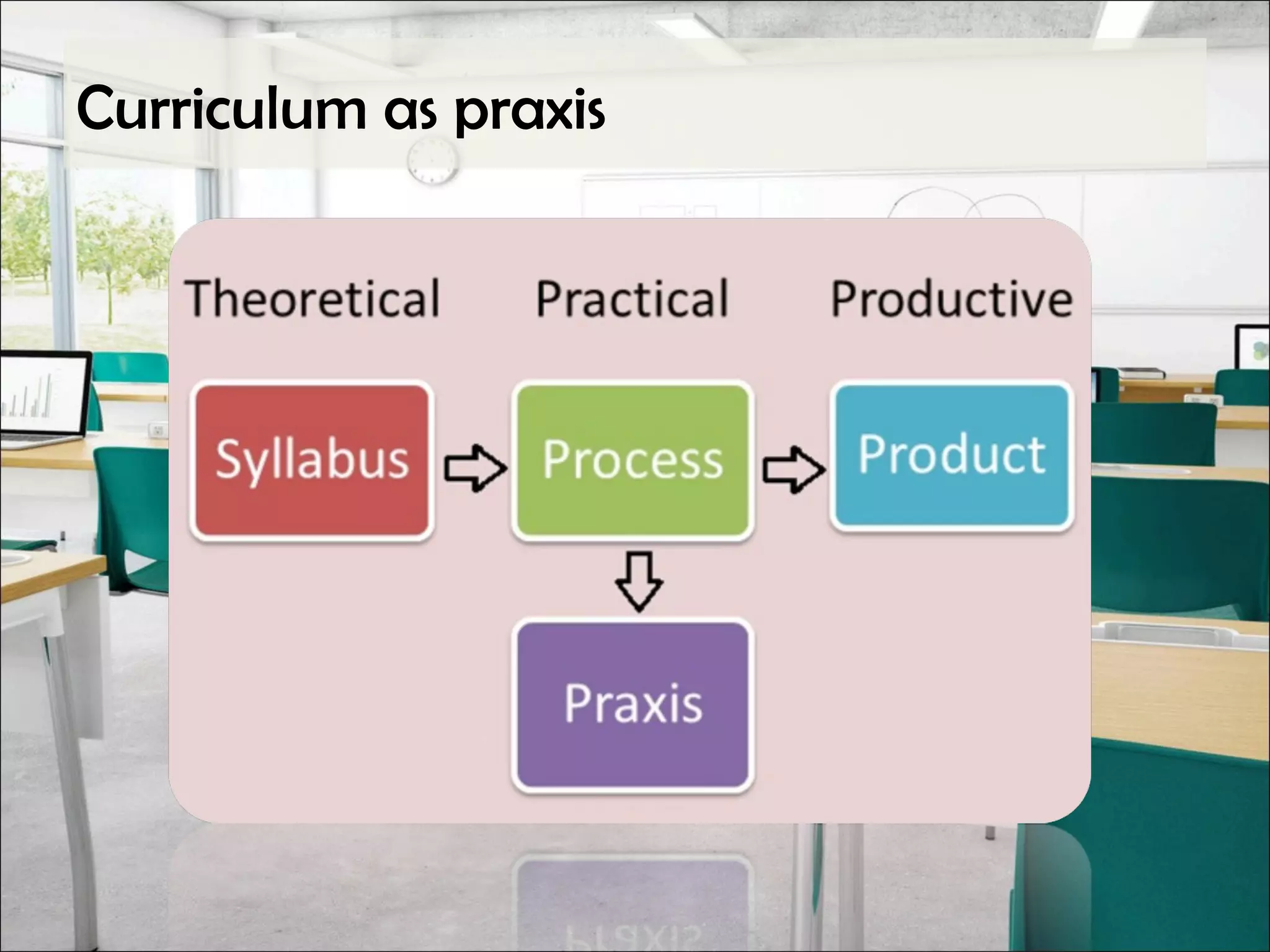

This document discusses key concepts related to curriculum design for teaching English as a foreign language. It defines curriculum as a general plan for a course of study including goals, learning outcomes, and evaluation. A syllabus provides more specific details for teaching a particular course, including content selection and sequencing. Methodology refers to the underlying teaching approaches used, while methods are specific classroom techniques. Effective curriculum design involves defining objectives, selecting content, organizing content and learning experiences, and determining evaluation. Curriculum ideologies influence design and include academic rationalism, social efficiency, learner-centeredness, and social reconstructionism.