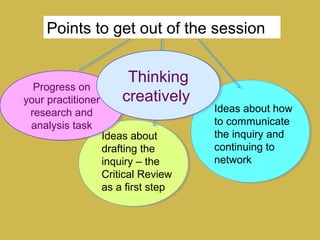

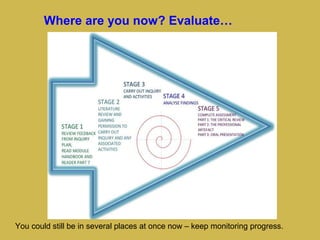

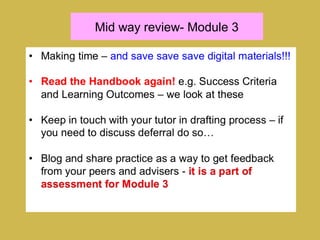

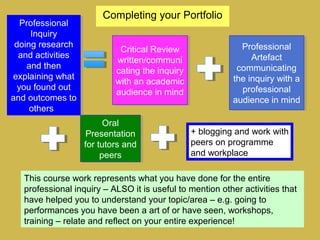

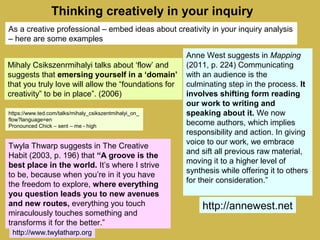

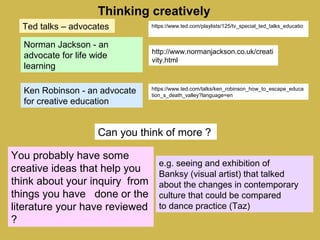

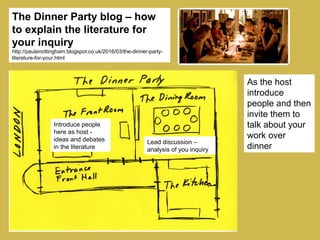

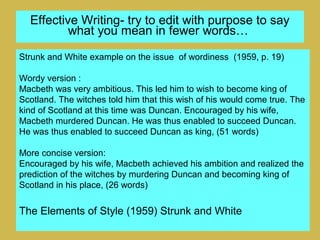

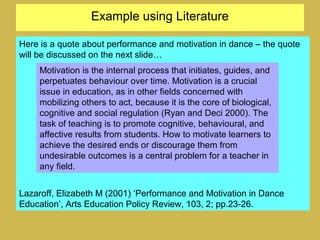

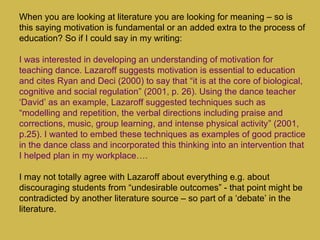

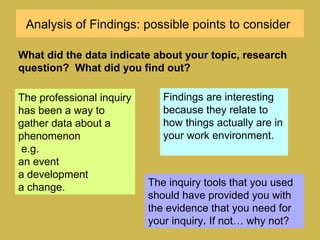

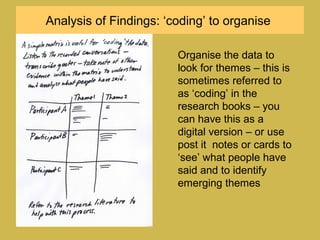

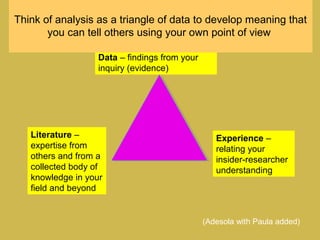

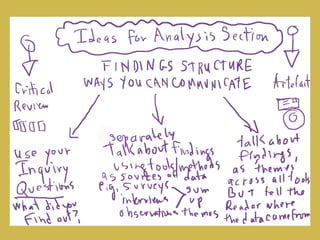

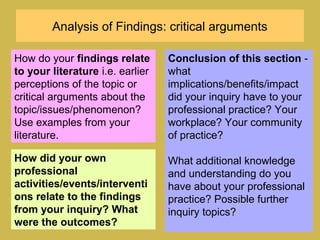

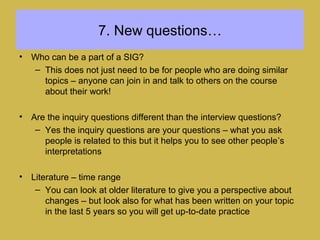

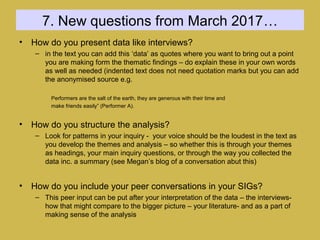

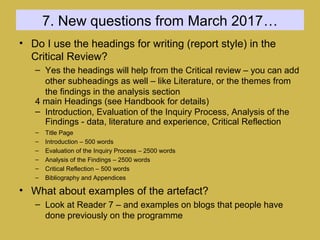

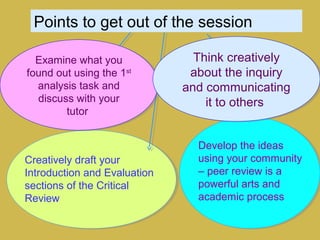

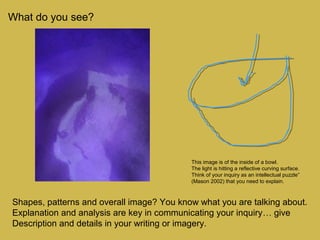

This document provides guidance for students on conducting a professional inquiry project. It discusses various aspects of the inquiry process, including thinking creatively, communicating findings, and drafting the written analysis. Students are encouraged to think about how to explain their topic and embed ideas from literature. Examples are provided on analyzing literature quotes and effectively writing the analysis section. The document concludes by looking ahead to sending a sample of the analysis for feedback and discussing how to organize findings by identifying themes in the data.