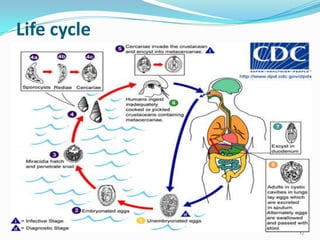

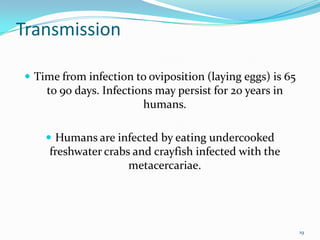

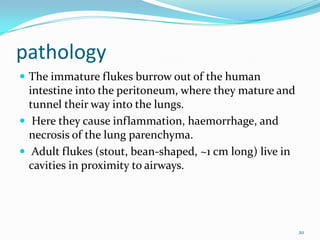

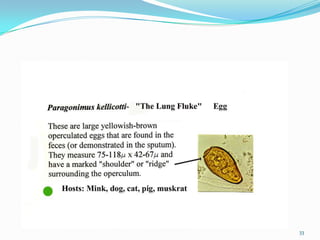

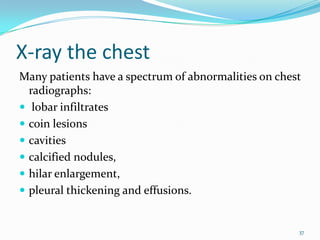

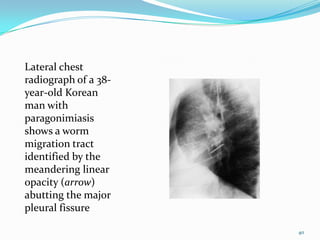

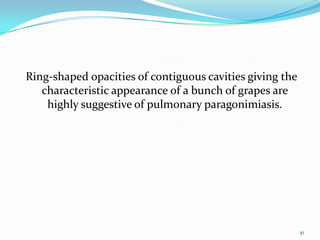

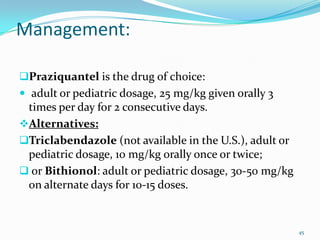

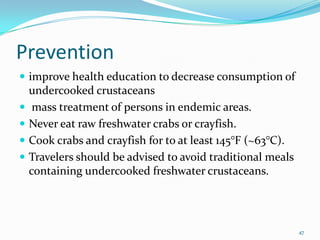

Paragonimiasis is caused by lung fluke parasites of the genus Paragonimus. People become infected by eating raw or undercooked freshwater crabs or crayfish containing infective parasite cysts. The parasites migrate through the intestines and lungs, causing inflammation and symptoms like coughing up blood. Diagnosis involves finding parasite eggs in sputum or stool samples under the microscope or using serology tests. Chest x-rays may also show signs of lung damage from migrating parasites. There is no vaccine and treatment involves antiparasitic medications.