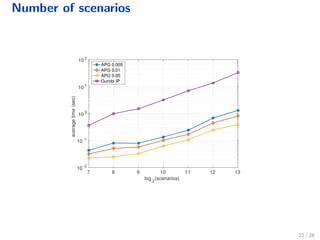

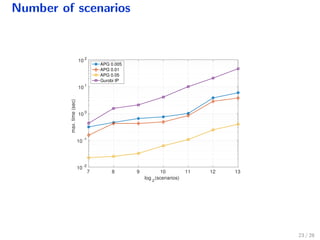

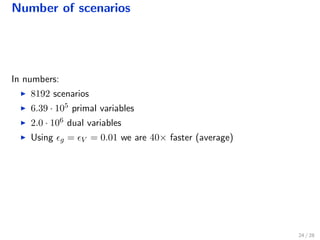

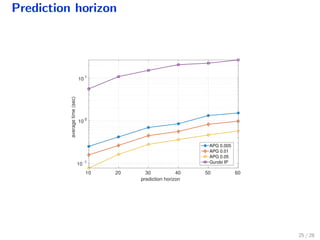

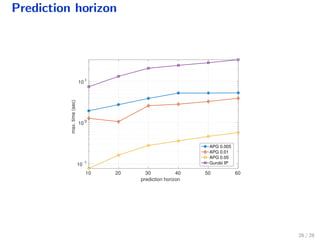

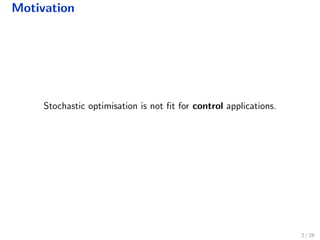

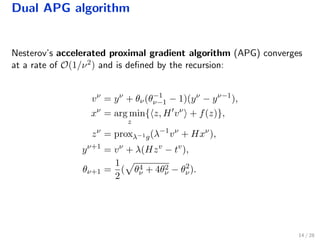

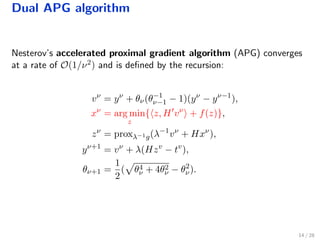

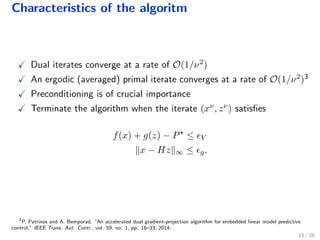

The document discusses a distributed solution for a stochastic optimal control problem using GPUs, highlighting the advantages of accelerated proximal gradient algorithms for solving complex control challenges across various applications like microgrids and drinking water networks. It includes a formulation of the optimization problem, details about the algorithm's implementation and performance, and presents simulation results demonstrating significant speed improvements compared to traditional methods like interior-point solvers. The findings indicate a substantial reduction in runtime, emphasizing the efficacy of GPU-based solutions for large-scale stochastic control systems.

![Applications

Microgrids [Hans et al. ’15]

Drinking water networks [Sampathirao et al. ’15]

HVAC [Long et al. ’13, Zhang et al. ’13, Parisio et al. ’13]

Financial systems [Patrinos et al. ’11, Bemporad et al., ’14]

Chemical process [Lucia et al. ’13]

Distillation column [Garrido and Steinbach, ’11]

1 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cdc2015-151218061929/85/Distributed-solution-of-stochastic-optimal-control-problem-on-GPUs-2-320.jpg)

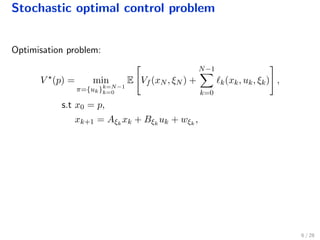

![Stochastic optimal control problem

Optimisation problem:

V (p) = min

π={uk}k=N−1

k=0

E Vf (xN , ξN ) +

N−1

k=0

k(xk, uk, ξk) ,

s.t x0 = p,

xk+1 = Aξk

xk + Bξk

uk + wξk

,

where:

E[·]: conditional expectation wrt the product probability measure

6 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cdc2015-151218061929/85/Distributed-solution-of-stochastic-optimal-control-problem-on-GPUs-9-320.jpg)

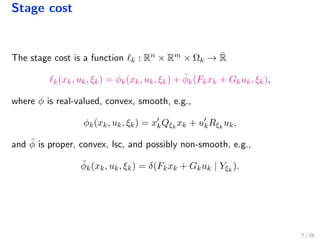

![Stochastic optimal control problem

Optimisation problem:

V (p) = min

π={uk}k=N−1

k=0

E Vf (xN , ξN ) +

N−1

k=0

k(xk, uk, ξk) ,

s.t x0 = p,

xk+1 = Aξk

xk + Bξk

uk + wξk

,

where:

E[·]: conditional expectation wrt the product probability measure

Casual policy uk = ψk(p,ξξξk−1), with ξξξk = (ξ0, ξ1, . . . , ξk)

6 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cdc2015-151218061929/85/Distributed-solution-of-stochastic-optimal-control-problem-on-GPUs-10-320.jpg)

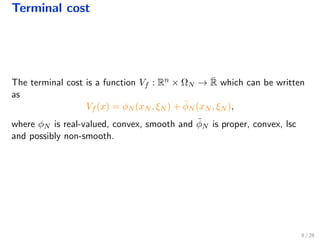

![Stochastic optimal control problem

Optimisation problem:

V (p) = min

π={uk}k=N−1

k=0

E Vf (xN , ξN ) +

N−1

k=0

k(xk, uk, ξk) ,

s.t x0 = p,

xk+1 = Aξk

xk + Bξk

uk + wξk

,

where:

E[·]: conditional expectation wrt the product probability measure

Casual policy uk = ψk(p,ξξξk−1), with ξξξk = (ξ0, ξ1, . . . , ξk)

and Vf can encode constraints

6 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cdc2015-151218061929/85/Distributed-solution-of-stochastic-optimal-control-problem-on-GPUs-11-320.jpg)

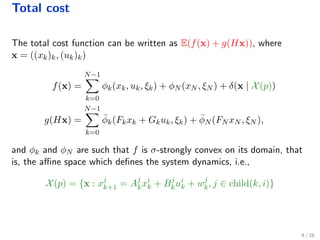

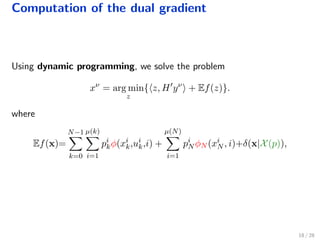

![Computation of the dual gradient

Factor step:

Performed once

Parallelisable

For time-invariant problems,

can be performed once offline

Algorithm 1 Solve step

qi

N ← yi

N , ∀i ∈ N[1,µ(N)], %Backward substitution

for k = N − 1, . . . , 0 do

for i ∈ µ(k) do {in parallel}

ui

k ← Φi

kyi

k + j∈child(k,i) Θ

j

k

q

j

k+1

+ σi

k

qi

k ← Di

k yi

k + j∈child(k,i) Λ

j

k

q

j

k+1

+ ci

k

end for

end for

x1

0 = p, %Forward substitution

for k = 0, . . . , N − 1 do

for i ∈ µ(k) do {in parallel}

ui

k ← Ki

kxi

k + ui

k

for j ∈ child(k, i) do {in parallel}

x

j

k+1

← A

j

k

xi

k + B

j

k

ui

k + w

j

k

end for

end for

end for

19 / 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cdc2015-151218061929/85/Distributed-solution-of-stochastic-optimal-control-problem-on-GPUs-28-320.jpg)