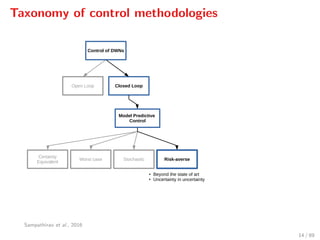

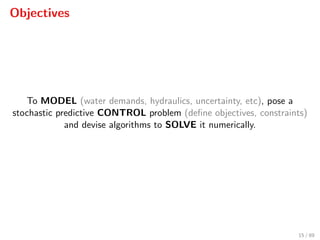

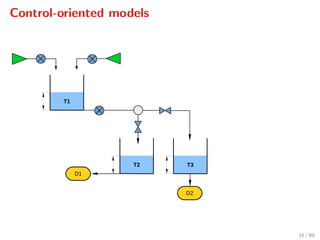

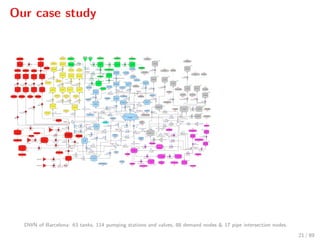

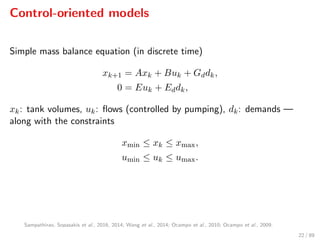

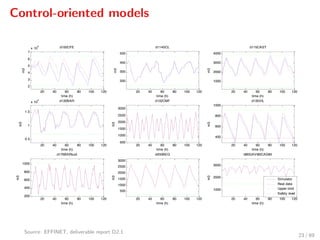

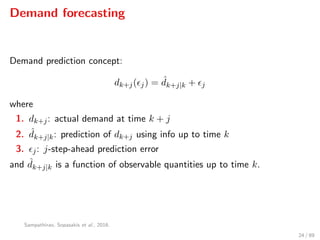

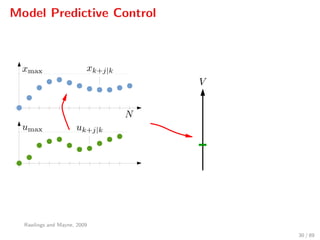

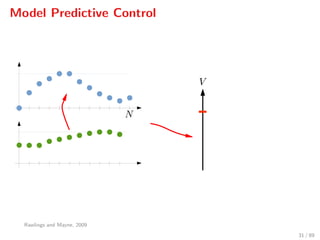

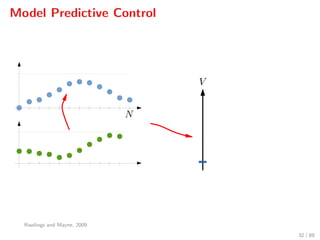

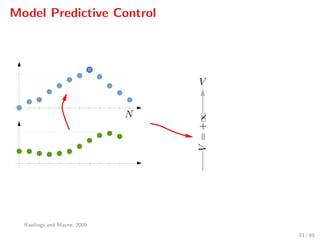

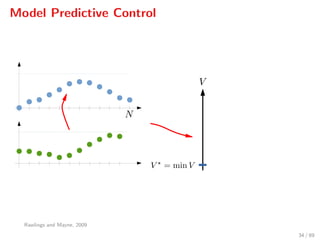

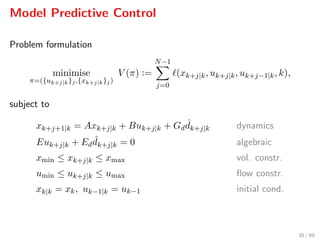

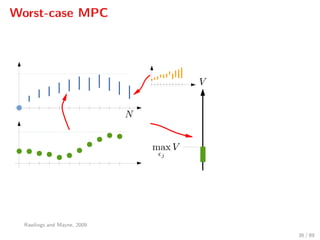

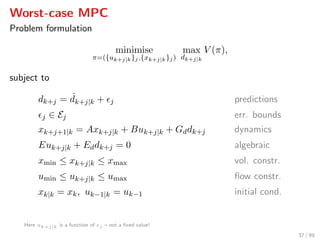

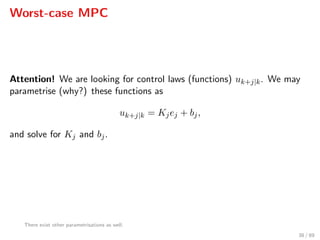

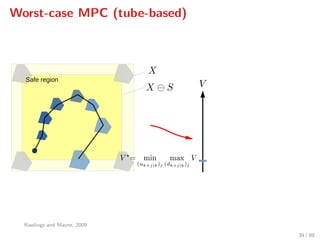

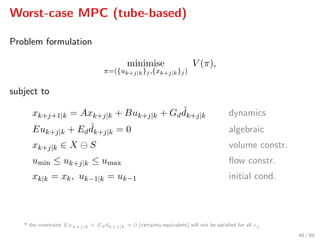

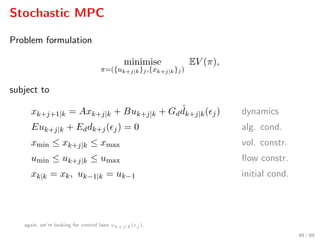

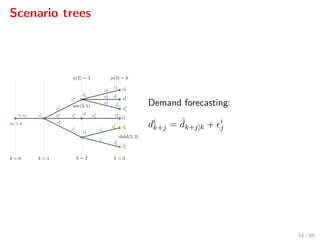

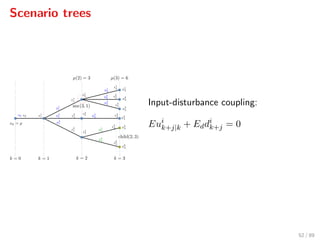

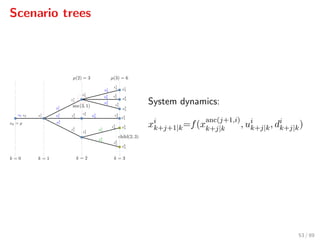

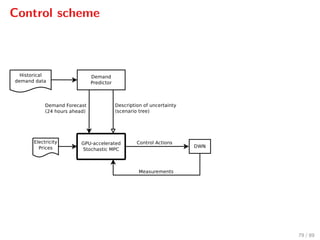

The document discusses advanced methodologies for modeling and controlling urban water networks, focusing on demand management and decision-making under uncertainty. It covers model predictive control (MPC) concepts, various control strategies including stochastic and worst-case MPC, and the importance of forecasting demand while considering constraints and objectives such as economic and safe operation costs. The case study illustrates the application of these methodologies to the water distribution network of Barcelona.

![Demand forecasting

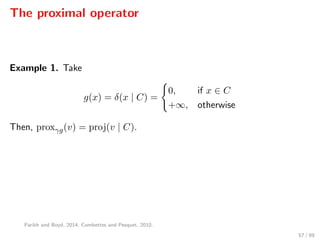

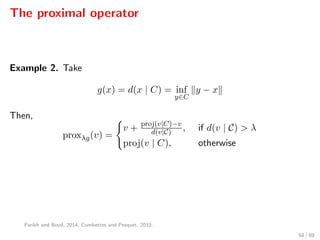

Common approaches:

1. Neglect the error: ( 0, 1, . . . , N ) (0, 0, . . . , 0)

2. Error bounds: ( 0, 1, . . . , N ) ∈ E, e.g., j ∈ [ min

j , max

j ]

25 / 89](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ascona-sopasakis-160824134758/85/Smart-Systems-for-Urban-Water-Demand-Management-29-320.jpg)

![Demand forecasting

Common approaches:

1. Neglect the error: ( 0, 1, . . . , N ) (0, 0, . . . , 0)

2. Error bounds: ( 0, 1, . . . , N ) ∈ E, e.g., j ∈ [ min

j , max

j ]

3. Independent normal distributions: j ∼ N(mj, σ2

j )

25 / 89](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ascona-sopasakis-160824134758/85/Smart-Systems-for-Urban-Water-Demand-Management-30-320.jpg)

![Demand forecasting

Common approaches:

1. Neglect the error: ( 0, 1, . . . , N ) (0, 0, . . . , 0)

2. Error bounds: ( 0, 1, . . . , N ) ∈ E, e.g., j ∈ [ min

j , max

j ]

3. Independent normal distributions: j ∼ N(mj, σ2

j )

4. ( 0, 1, . . . , N ) is random and admits finitely many values

25 / 89](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ascona-sopasakis-160824134758/85/Smart-Systems-for-Urban-Water-Demand-Management-31-320.jpg)

![Error bounds

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 200

0

0.01

0.02

0.03

0.04

0.05

0.06

0.07

Time [h]

WaterDemandFlow[m

3

/h]

Forecasting of Water Demand

FuturePast

26 / 89](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ascona-sopasakis-160824134758/85/Smart-Systems-for-Urban-Water-Demand-Management-32-320.jpg)

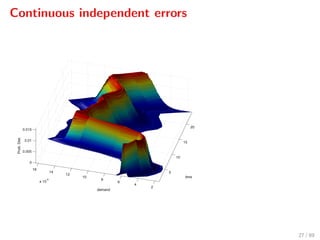

![Predicted scenarios

Time [hr]

4370 4380 4390 4400 4410 4420 4430

Waterdemand[m

3

/s]

0.01

0.015

0.02

0.025

0.03

0.035

0.04

0.045

0.05

28 / 89](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ascona-sopasakis-160824134758/85/Smart-Systems-for-Urban-Water-Demand-Management-34-320.jpg)

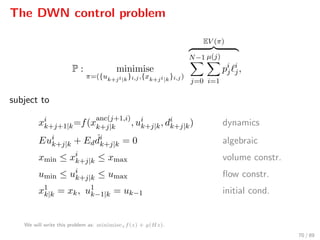

![Control objectives

Stage costs:

1. Economic cost: w(uk, k) = Wα(α1 + α2,k) uk

2. Smooth operation cost: ∆(∆uk) = ∆ukWu∆uk

3. Safe operation cost: S(xk) = Wx [xs − xk]+

We define ∆uk = uk − uk−1

Sampathirao et al., 2014; Cong Cong et al., 2014

29 / 89](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ascona-sopasakis-160824134758/85/Smart-Systems-for-Urban-Water-Demand-Management-37-320.jpg)

![Control objectives

Stage costs:

1. Economic cost: w(uk, k) = Wα(α1 + α2,k) uk

2. Smooth operation cost: ∆(∆uk) = ∆ukWu∆uk

3. Safe operation cost: S(xk) = Wx [xs − xk]+

4. Total cost: = w + ∆ + S.

We define ∆uk = uk − uk−1

Sampathirao et al., 2014; Cong Cong et al., 2014

29 / 89](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ascona-sopasakis-160824134758/85/Smart-Systems-for-Urban-Water-Demand-Management-38-320.jpg)

![Closed-loop simulations

20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160

Controlaction[%]

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

Time [hr]

20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160

WaterCost[e.u.]

60

70

80

90

86 / 89](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ascona-sopasakis-160824134758/85/Smart-Systems-for-Urban-Water-Demand-Management-101-320.jpg)