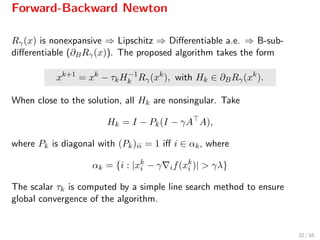

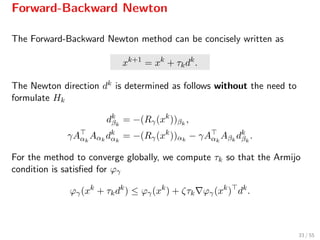

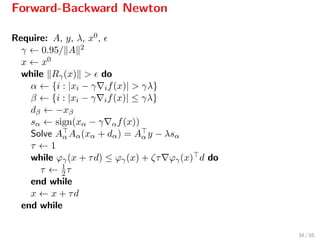

The document discusses a proposed method for recursive compressed sensing, demonstrating that it is significantly faster than existing methods. It covers various optimization techniques including forward-backward splitting and Newton methods, and their applications in solving sparse coding problems. Additionally, simulations and the implications of this method in fields like MRI, radio-astronomy, and medical imaging are highlighted.

![Forward-Backward Splitting

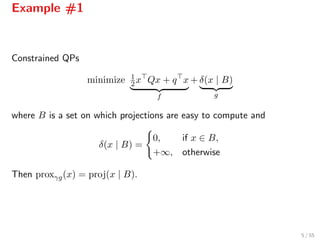

Problem structure

minimize ϕ(x) = f(x) + g(x)

where

1. f, g : Rn → ¯R are proper, closed, convex

2. f has L-Lipschitz gradient

3. g is prox-friendly, i.e., its proximal operator

proxγg(v) := arg min

z

g(z) + 1

2 v − z 2

is easily computable[1]

.

[1]

Parikh & Boyd 2014; Combettes & Pesquette, 2010.

4 / 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rcs-160412145939/85/Recursive-Compressed-Sensing-6-320.jpg)

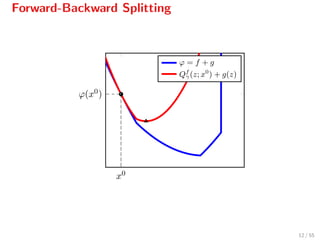

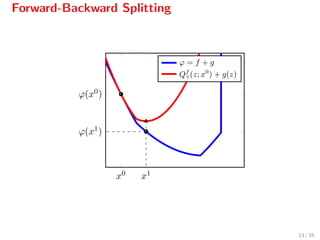

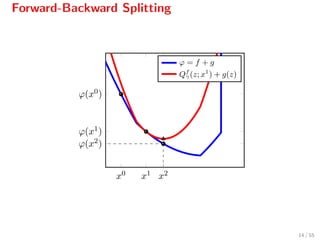

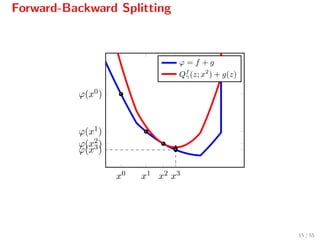

![Forward-Backward Splitting

The iteration

xk+1

= proxγg(xk

− γ f(xk

)),

can be written as[2]

xk+1

= arg min

z

f(xk

) + f(xk

), z − xk

+ 1

2γ z − xk 2

Qf

γ(z,xk)

+g(z) ,

where Qf

γ(z, xk) serves as a quadratic model for f[3]

.

[2]

Beck and Teboulle, 2010.

[3]

Qf

γ (·, xk

) is the linearization of f at xk

plus a quadratic term; moreover, Qf

γ (z, xk

) ≥ f(x) and Qf

γ (z, z) = f(z).

9 / 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rcs-160412145939/85/Recursive-Compressed-Sensing-11-320.jpg)

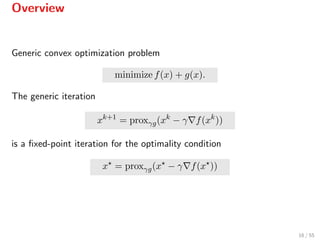

![Overview

It generalizes several other methods

xk+1

=

xk − γ f(xk) gradient method, g = 0

ΠC(xk − γ f(xk)) gradient projection, g = δ(· | C)

proxγg(xk) proximal point algorithm, f = 0

There are several flavors of proximal gradient algorithms[4]

.

[4]

Nesterov’s accelerated method, FISTA (Beck & Teboulle), etc.

17 / 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rcs-160412145939/85/Recursive-Compressed-Sensing-19-320.jpg)

![Shortcomings

FBS are first-order methods, therefore, they can be slow!

Overhaul. Use a better quadratic model for f[5]

:

Qf

γ,B(z, xk

) = f(xk

) + f(xk

), z − xk

+ 1

2γ z − xk 2

Bk ,

where Bk is (an approximation of) 2f(x).

Drawback. No closed form solution of the inner problem.

[5]

As in Becker & Fadili 2012; Lee et al. 2012; Tran-Dinh et al. 2013.

18 / 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rcs-160412145939/85/Recursive-Compressed-Sensing-20-320.jpg)

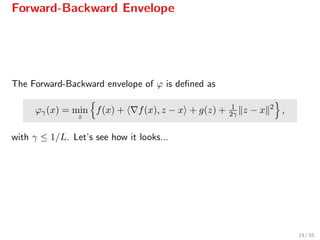

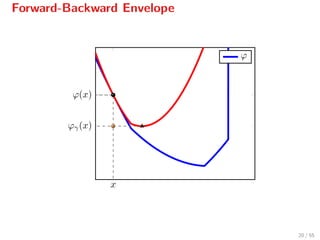

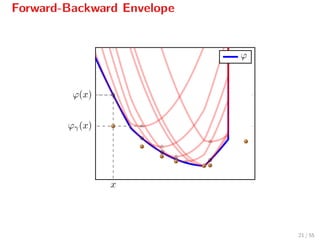

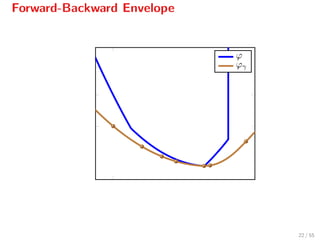

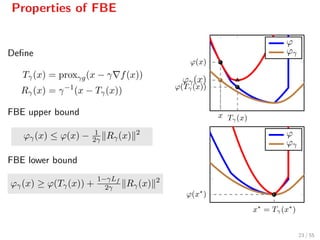

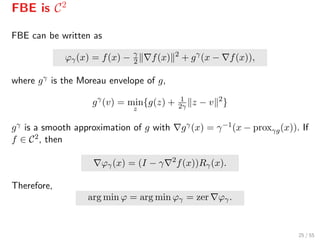

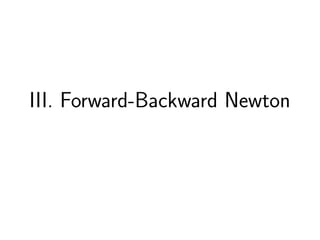

![Properties of FBE

Ergo: Minimizing ϕ is equivalent to minimizing its FBE ϕγ.

inf ϕ = inf ϕγ

arg min ϕ = arg min ϕγ

However, ϕγ is continuously diff/able[6]

whenever f ∈ C2.

[6]

More about the FBE: P. Patrinos, L. Stella and A. Bemporad, 2014.

24 / 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rcs-160412145939/85/Recursive-Compressed-Sensing-27-320.jpg)

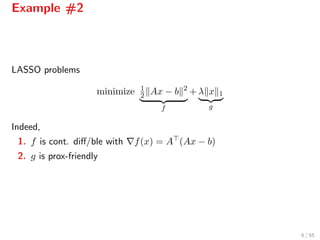

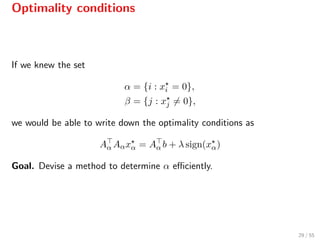

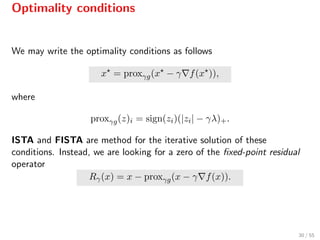

![Optimality conditions

LASSO problem

minimize 1

2 Ax − b 2

f

+ λ x 1

g

.

Optimality conditions

− f(x ) ∈ ∂g(x ).

where f(x) = A (Ax − b) and ∂g(x)i = λ sign(xi) for xi = 0 and

∂g(x)i = [−λ, λ] otherwise, so

− if(x ) = λ sign(xi ), if xi = 0,

| if(x )| ≤ λ, otherwise

28 / 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rcs-160412145939/85/Recursive-Compressed-Sensing-32-320.jpg)

![B-subdifferential

For a function F : Rn → Rn which is almost everywhere differentiable, we

define its B-subdifferential to be[7]

∂BF(x) := B ∈ Rn×n ∃{xn}n : xn → x,

Rγ(xn) exists and Rγ(xn) → B

.

[7]

See Facchinei & Pang, 2004

31 / 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rcs-160412145939/85/Recursive-Compressed-Sensing-35-320.jpg)

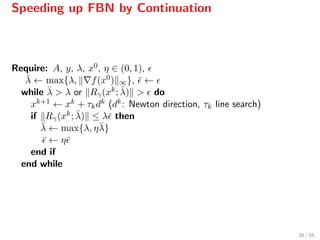

![Speeding up FBN by Continuation

1. In applications of LASSO we have x 0 ≤ m n[8]

[8]

The zero-norm of x, x 0, is the number of its nonzeroes.

35 / 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rcs-160412145939/85/Recursive-Compressed-Sensing-39-320.jpg)

![Speeding up FBN by Continuation

1. In applications of LASSO we have x 0 ≤ m n[8]

2. If λ ≥ λ0 := f(x0) ∞, then supp(x) = ∅

[8]

The zero-norm of x, x 0, is the number of its nonzeroes.

35 / 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rcs-160412145939/85/Recursive-Compressed-Sensing-40-320.jpg)

![Speeding up FBN by Continuation

1. In applications of LASSO we have x 0 ≤ m n[8]

2. If λ ≥ λ0 := f(x0) ∞, then supp(x) = ∅

3. We relax the optimization problem solving

P(¯λ) : minimize 1

2 Ax − y 2

+ ¯λ x 1

[8]

The zero-norm of x, x 0, is the number of its nonzeroes.

35 / 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rcs-160412145939/85/Recursive-Compressed-Sensing-41-320.jpg)

![Speeding up FBN by Continuation

1. In applications of LASSO we have x 0 ≤ m n[8]

2. If λ ≥ λ0 := f(x0) ∞, then supp(x) = ∅

3. We relax the optimization problem solving

P(¯λ) : minimize 1

2 Ax − y 2

+ ¯λ x 1

4. Once we have approximately solved P(¯λ) we update ¯λ as

¯λ ← max{η¯λ, λ},

until eventually ¯λ = λ.

[8]

The zero-norm of x, x 0, is the number of its nonzeroes.

35 / 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rcs-160412145939/85/Recursive-Compressed-Sensing-42-320.jpg)

![Speeding up FBN by Continuation

1. In applications of LASSO we have x 0 ≤ m n[8]

2. If λ ≥ λ0 := f(x0) ∞, then supp(x) = ∅

3. We relax the optimization problem solving

P(¯λ) : minimize 1

2 Ax − y 2

+ ¯λ x 1

4. Once we have approximately solved P(¯λ) we update ¯λ as

¯λ ← max{η¯λ, λ},

until eventually ¯λ = λ.

5. This way we enforce that (i) |αk| increases smoothly, (ii) |αk| < m,

(iii) Aαk

Aαk

remains always positive definite.

[8]

The zero-norm of x, x 0, is the number of its nonzeroes.

35 / 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rcs-160412145939/85/Recursive-Compressed-Sensing-43-320.jpg)

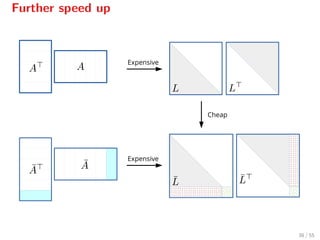

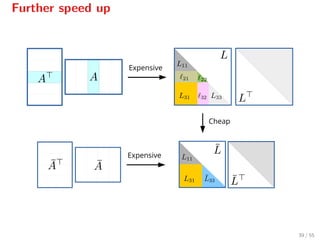

![Further speed up

When Aα is positive definite[9]

, we may compute a Cholesky factorization

of Aα0

Aα0 and then update the Cholesky factorization of Aαk+1

Aαk+1

using the factorization of Aαk

Aαk

.

[9]

In practice, always (when the continuation heuristic is used). Furthermore, α0 = ∅.

37 / 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rcs-160412145939/85/Recursive-Compressed-Sensing-45-320.jpg)

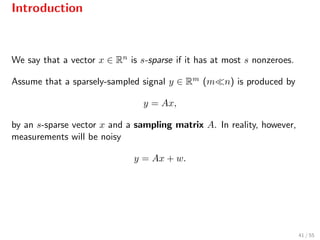

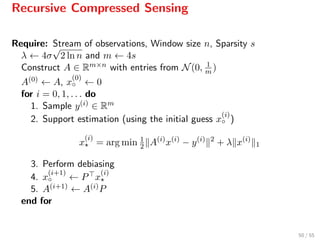

![Sparse Sampling

We require that A satisfies the restricted isometry property[10]

, that is

(1 − δs) x 2

≤ Ax 2

≤ (1 + δs) x 2

A typical choice is a random matrix A with entries drawn from N(0, 1

m )

with m = 4s.

[10]

This can be established using the Johnson-Lindenstrauss lemma.

43 / 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rcs-160412145939/85/Recursive-Compressed-Sensing-52-320.jpg)

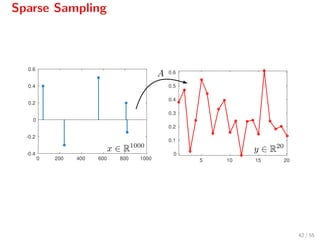

![Decompression

Assuming that

w ∼ N(0, σ2I),

the smallest element of |x| is not too small (> 8σ

√

2 ln n),

λ = 4σ

√

2 ln n,

the LASSO recovers the support of x[11]

, that is

x = arg min 1

2 Ax − y 2

+ λ x 1,

has the same support as the actual x.

[11]

Cand`es & Plan, 2009.

44 / 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rcs-160412145939/85/Recursive-Compressed-Sensing-53-320.jpg)

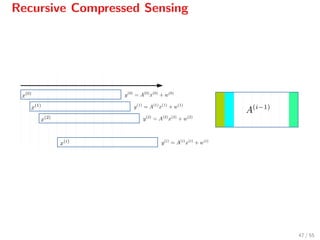

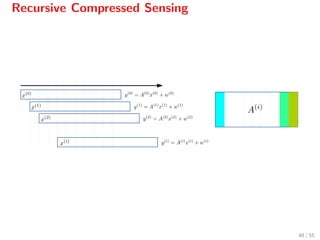

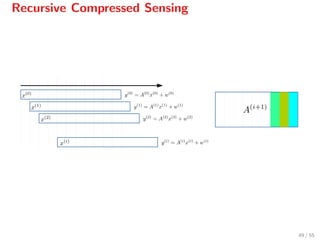

![Recursive Compressed Sensing

Define

x(i)

:= xi xi+1 · · · xi+n−1

Then x(i) produces the measured signal

y(i)

= A(i)

x(i)

+ w(i)

.

Sampling is performed with a constant matrix A[12]

and

A(0)

= A,

A(i+1)

= A(i)

P,

where P is a permutation matrix which shifts the columns of A leftwards.

[12]

For details see: N. Freris, O. ¨O¸cal and M. Vetterli, 2014.

46 / 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rcs-160412145939/85/Recursive-Compressed-Sensing-55-320.jpg)

![Simulations

For a 10%-sparse stream

Window size ×10 4

0.5 1 1.5 2

Averageruntime[s]

10 -1

10 0

10 1

FBN

FISTA

ADMM

L1LS

52 / 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rcs-160412145939/85/Recursive-Compressed-Sensing-62-320.jpg)

![Simulations

For n = 5000 varying the stream sparsity

Sparsity [%]

0 5 10 15

Averageruntime[s]

10 -1

10 0

FBN

FISTA

ADMM

L1LS

53 / 55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rcs-160412145939/85/Recursive-Compressed-Sensing-63-320.jpg)