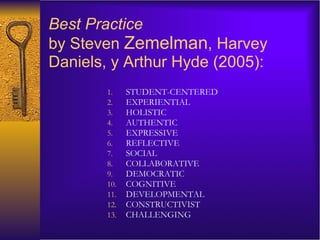

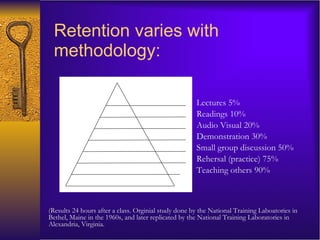

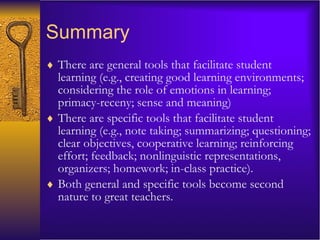

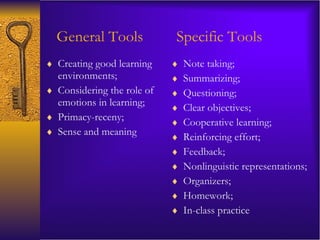

This document summarizes best practices and tools for teaching in multilingual classrooms. It discusses both general tools like considering learning environments and emotions, as well as specific tools such as note-taking, summarizing, questioning techniques, and cooperative learning. Both general and specific tools can become second nature for effective teachers. The document recommends choosing one unfamiliar tool to apply in teaching, such as using organizers, reinforcing effort, or providing feedback.

![For more information: Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa, Ph.D. Universidad San Francisco de Quito Edif. Galileo #101 Telf: +593 2 297-1700 x1338 o +593-2-297-18937 [email_address] Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa is a professor of Education and Psychology at the Universidad San Francisco de Quito in Ecuador at the undergraduate and Master’s levels. Tracey received her doctorate (PhD) in the new field of Mind, Brain, and Education Science in July 2008 (Capella University), her Master’s of Education from Harvard University (International Development) and her Bachelor’s of Arts (International Relations) and Bachelor’s of Science (Communications) from Boston University, magna cum laude .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/toolboxforbetterteachingrotterdammonday-091119082158-phpapp01/85/Toolbox-for-better-teaching-31-320.jpg)