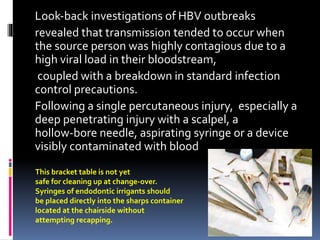

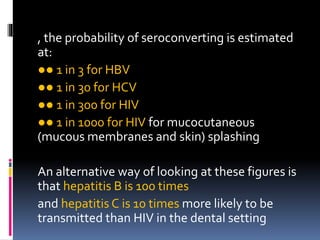

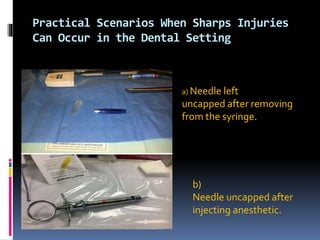

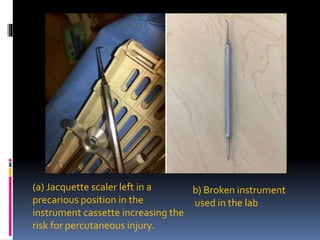

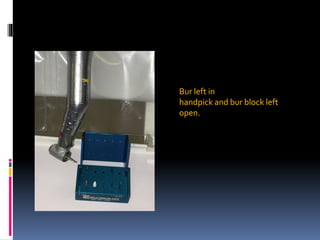

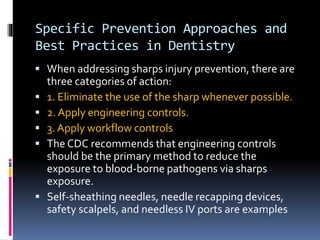

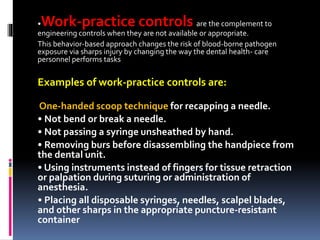

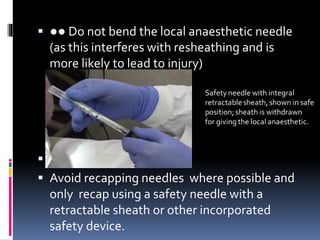

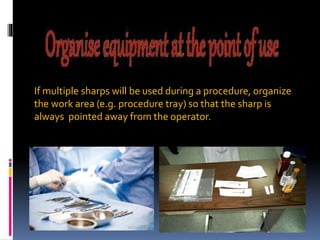

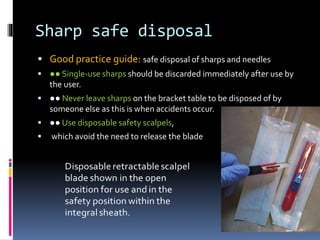

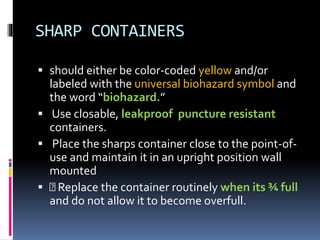

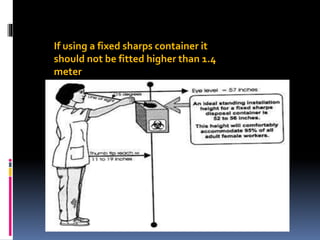

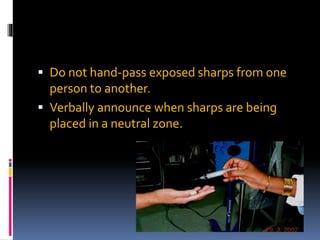

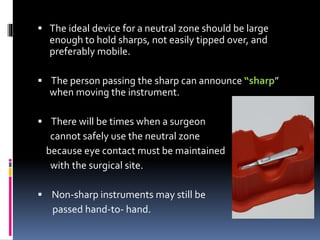

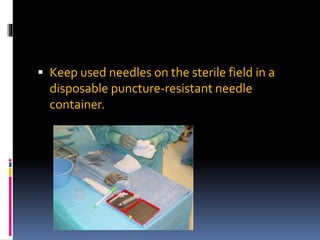

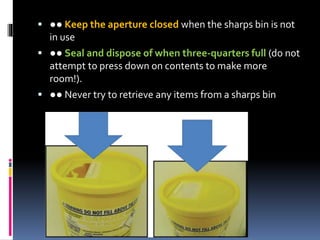

This document provides guidance on safe working practices involving sharp instruments in dental surgeries. It discusses why sharp injury prevention is important to avoid transmission of bloodborne viruses. Common scenarios where sharp injuries can occur are described, such as needlestick injuries during recapping. Engineering controls and work practice guidelines are recommended to minimize risks. Proper disposal of sharps in puncture-resistant containers is also covered. The document aims to educate dental practitioners on best practices for avoiding sharp injuries.