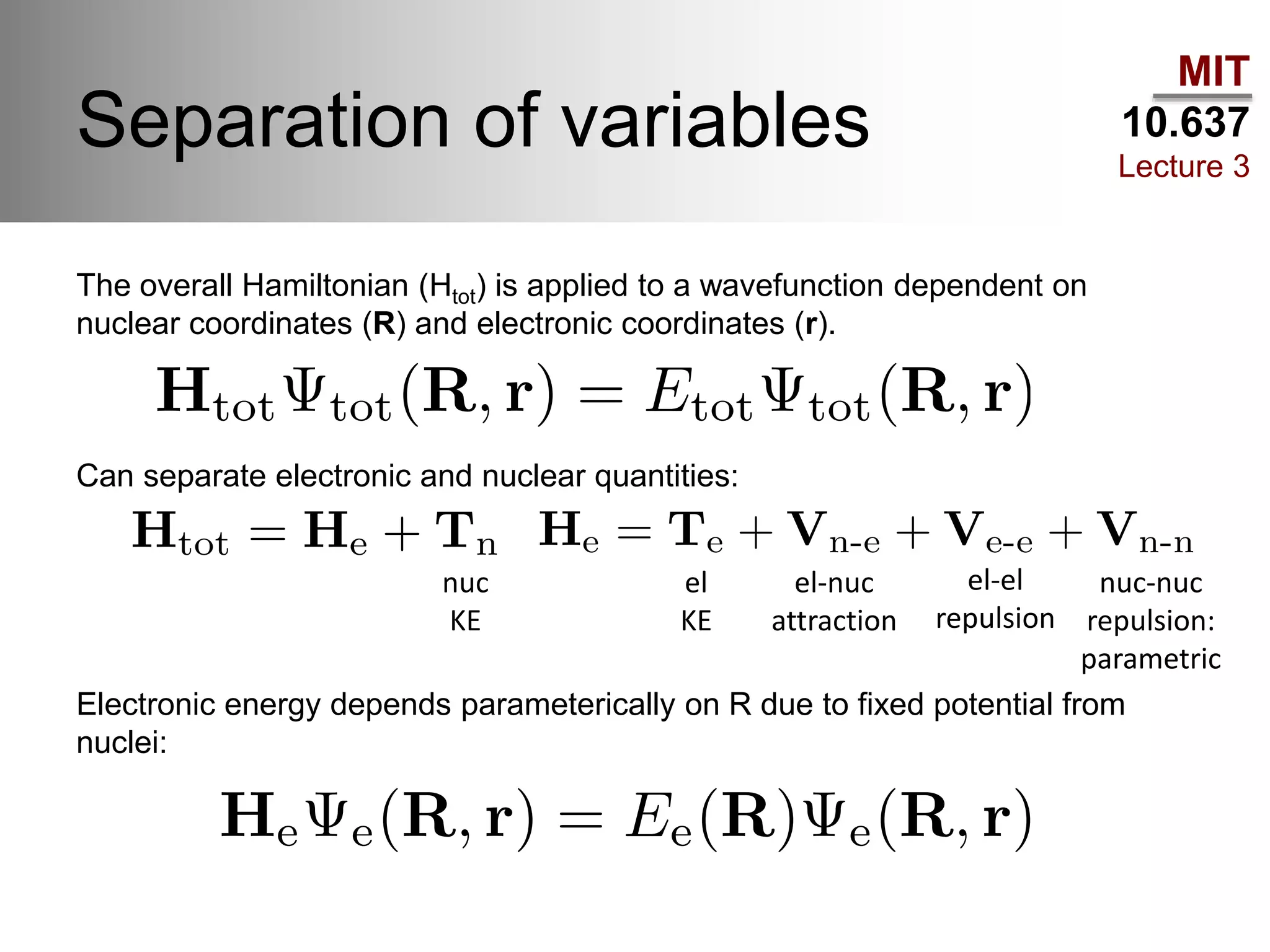

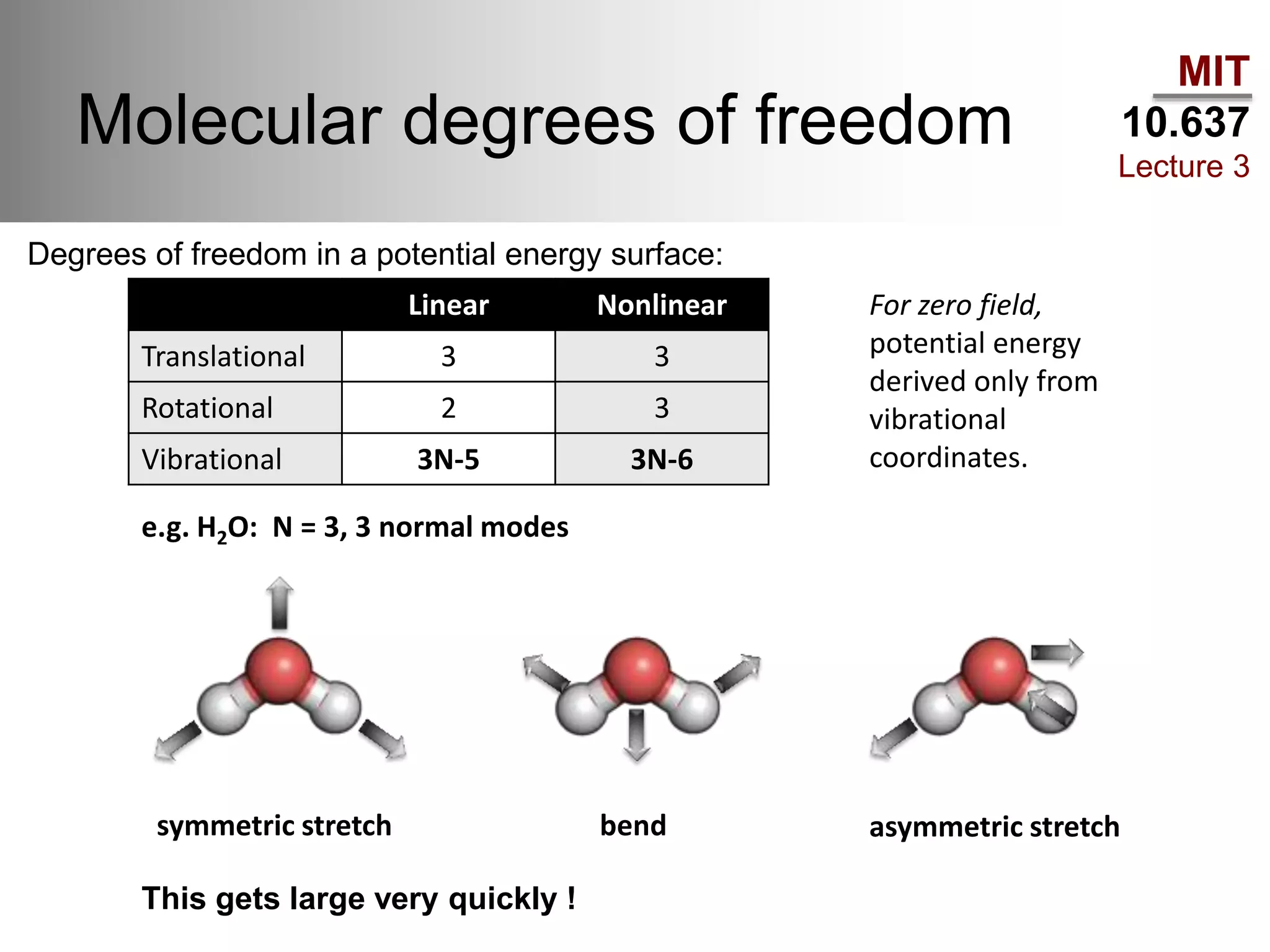

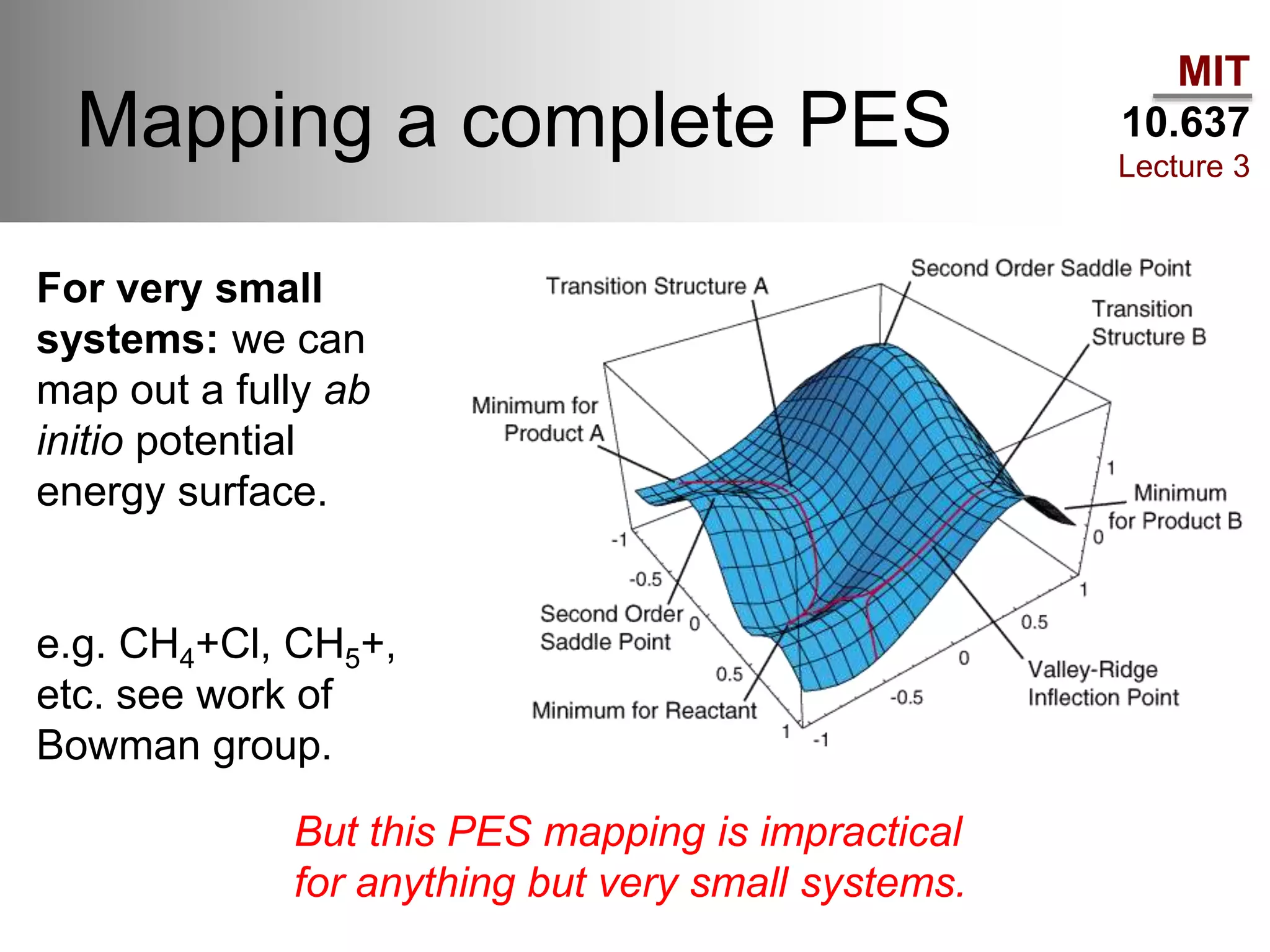

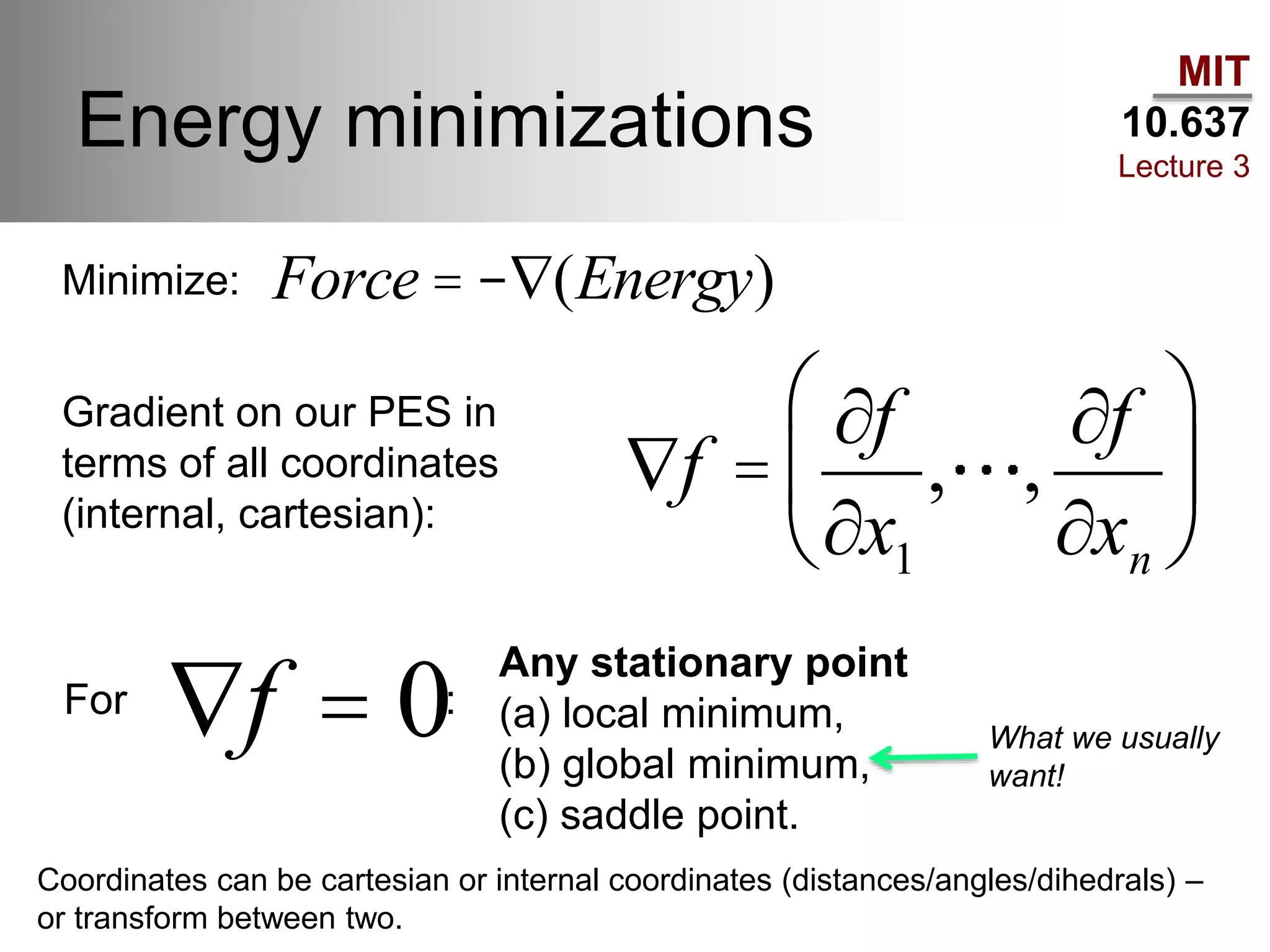

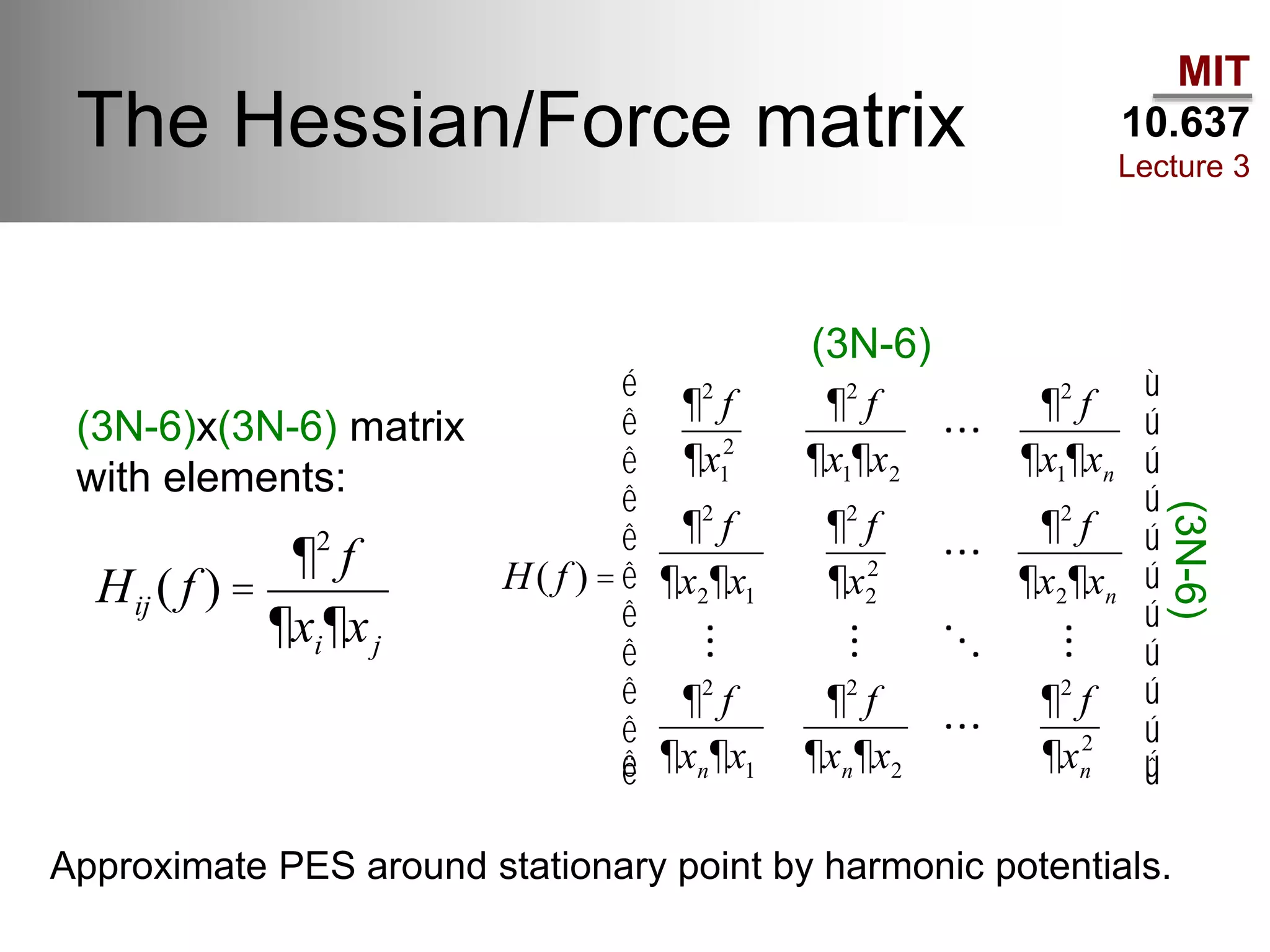

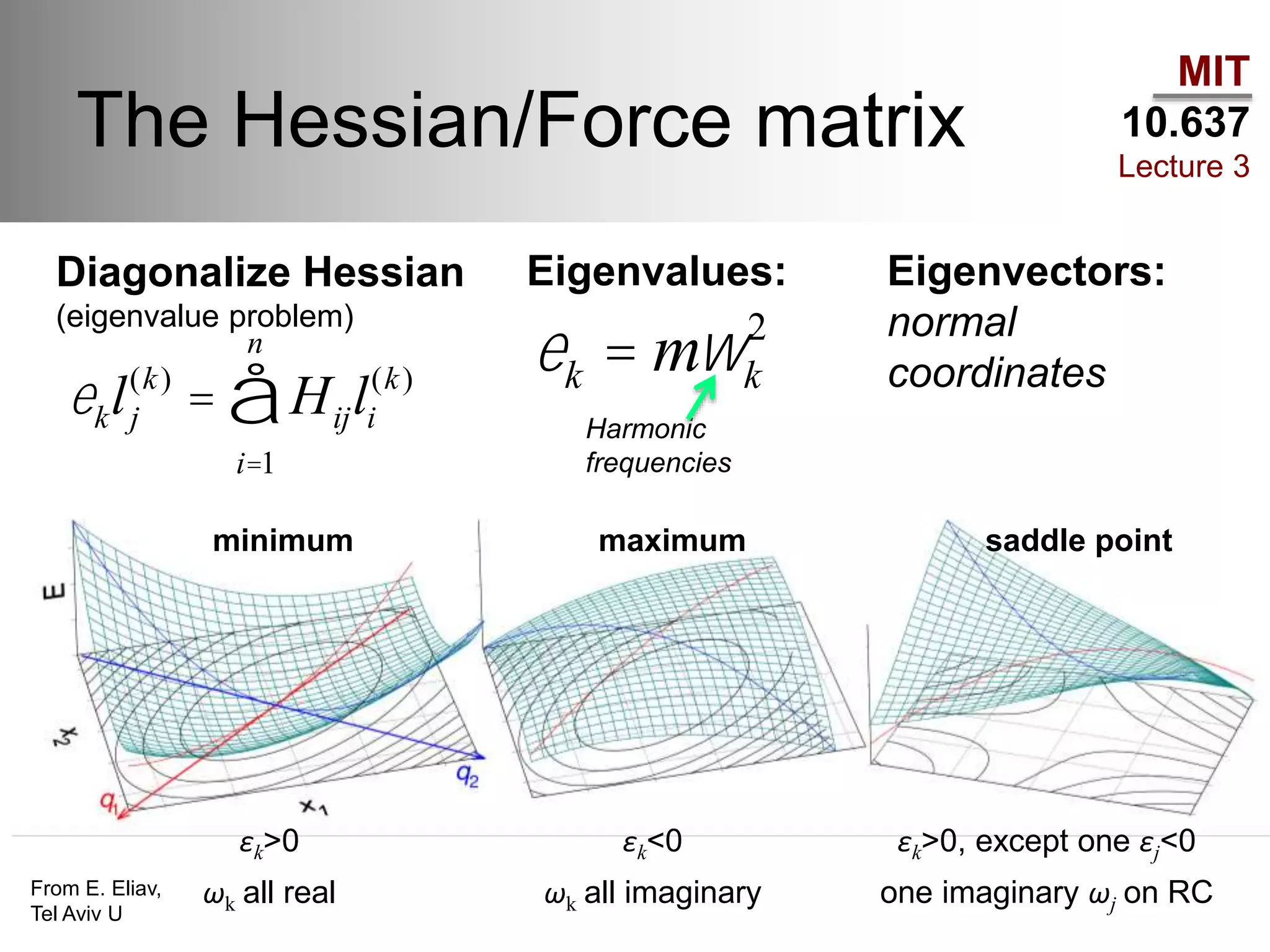

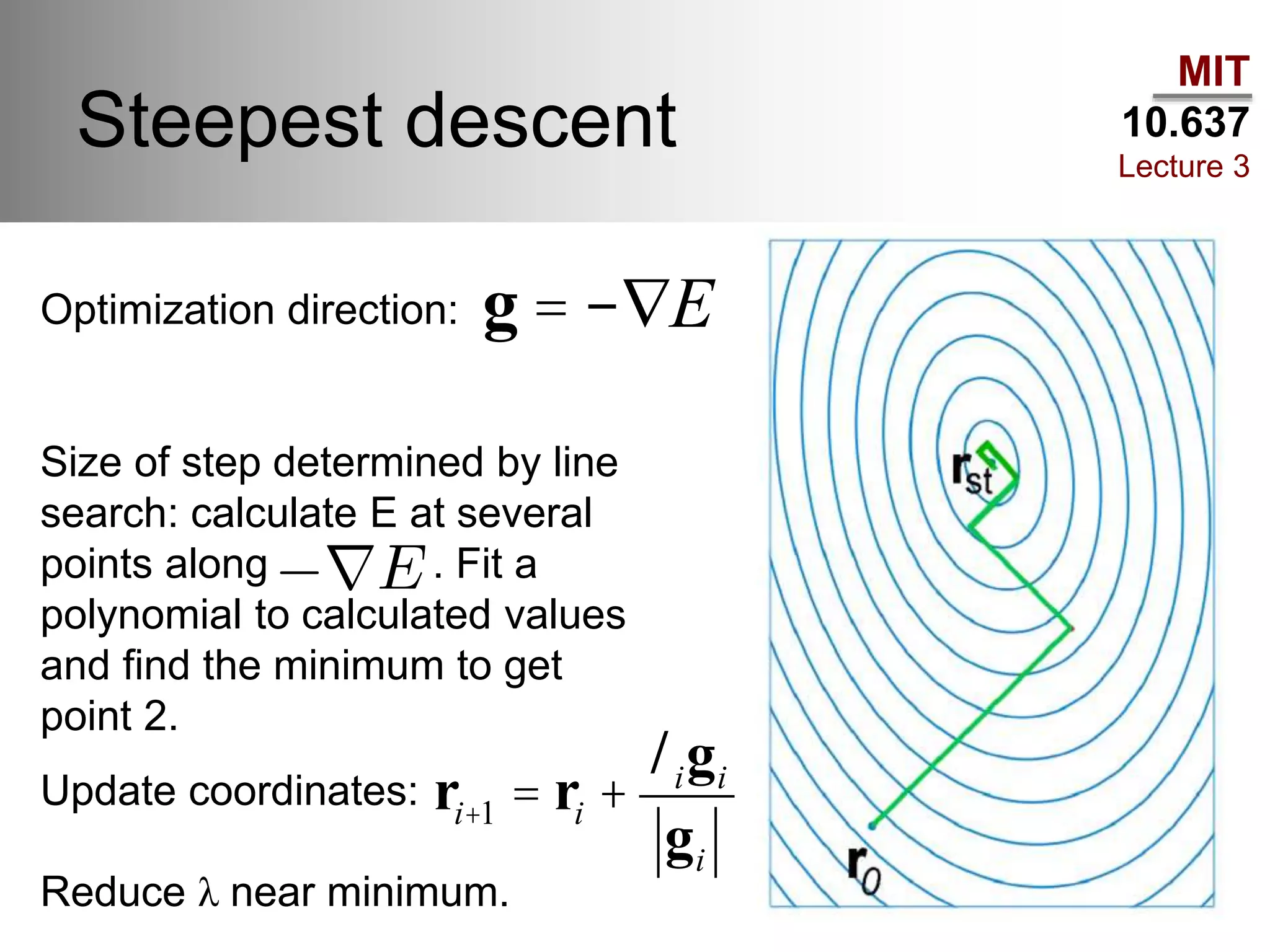

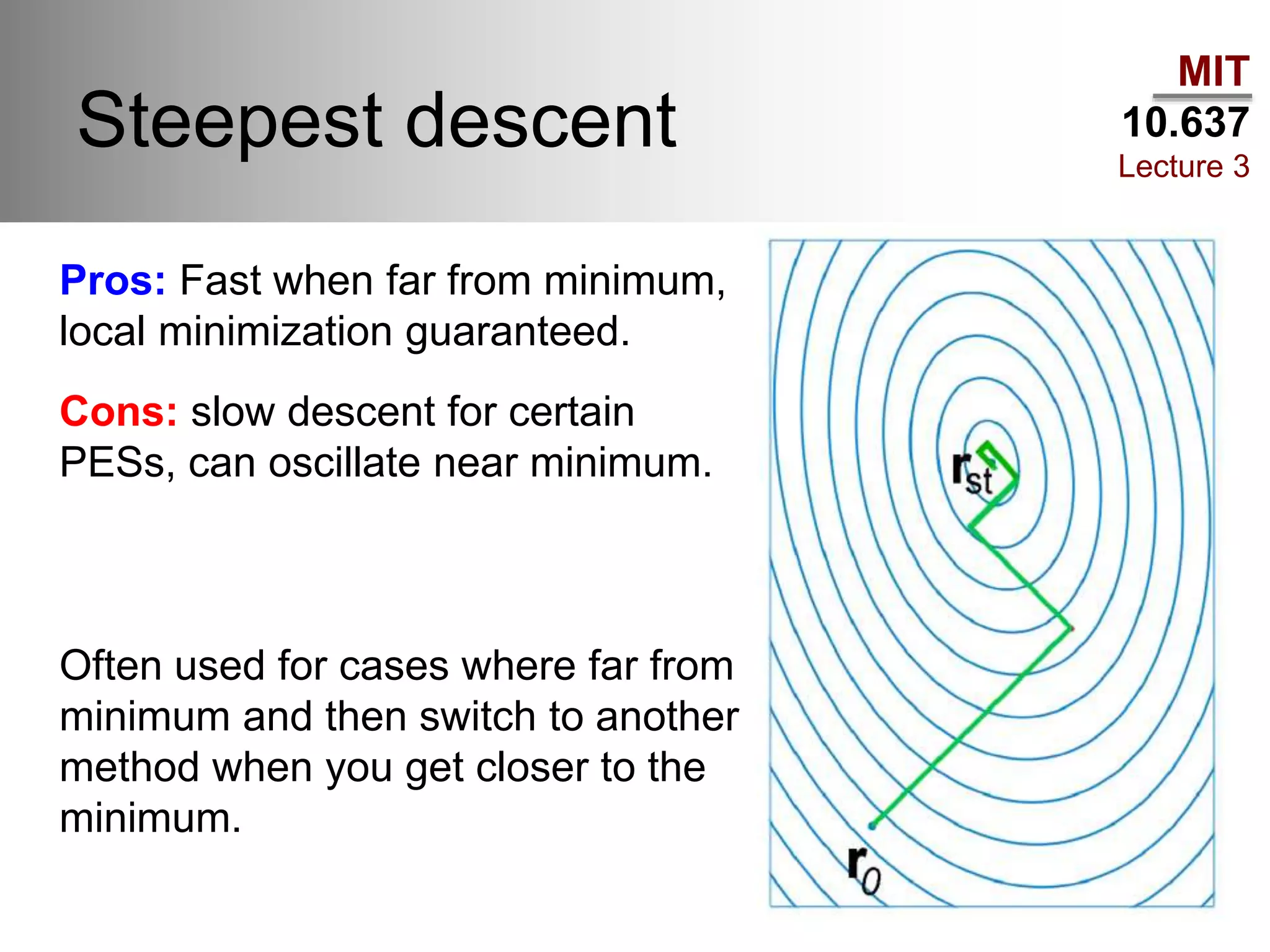

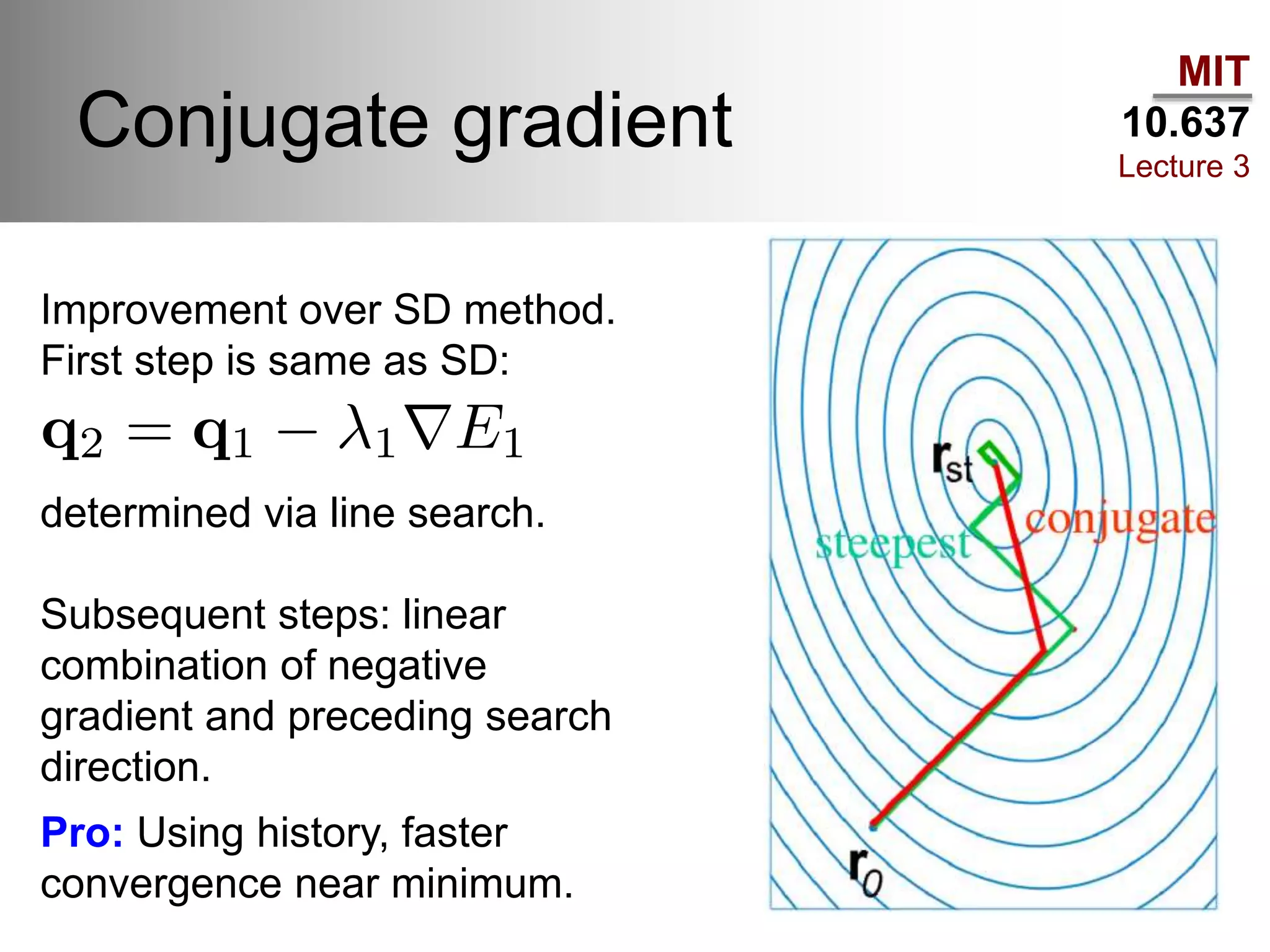

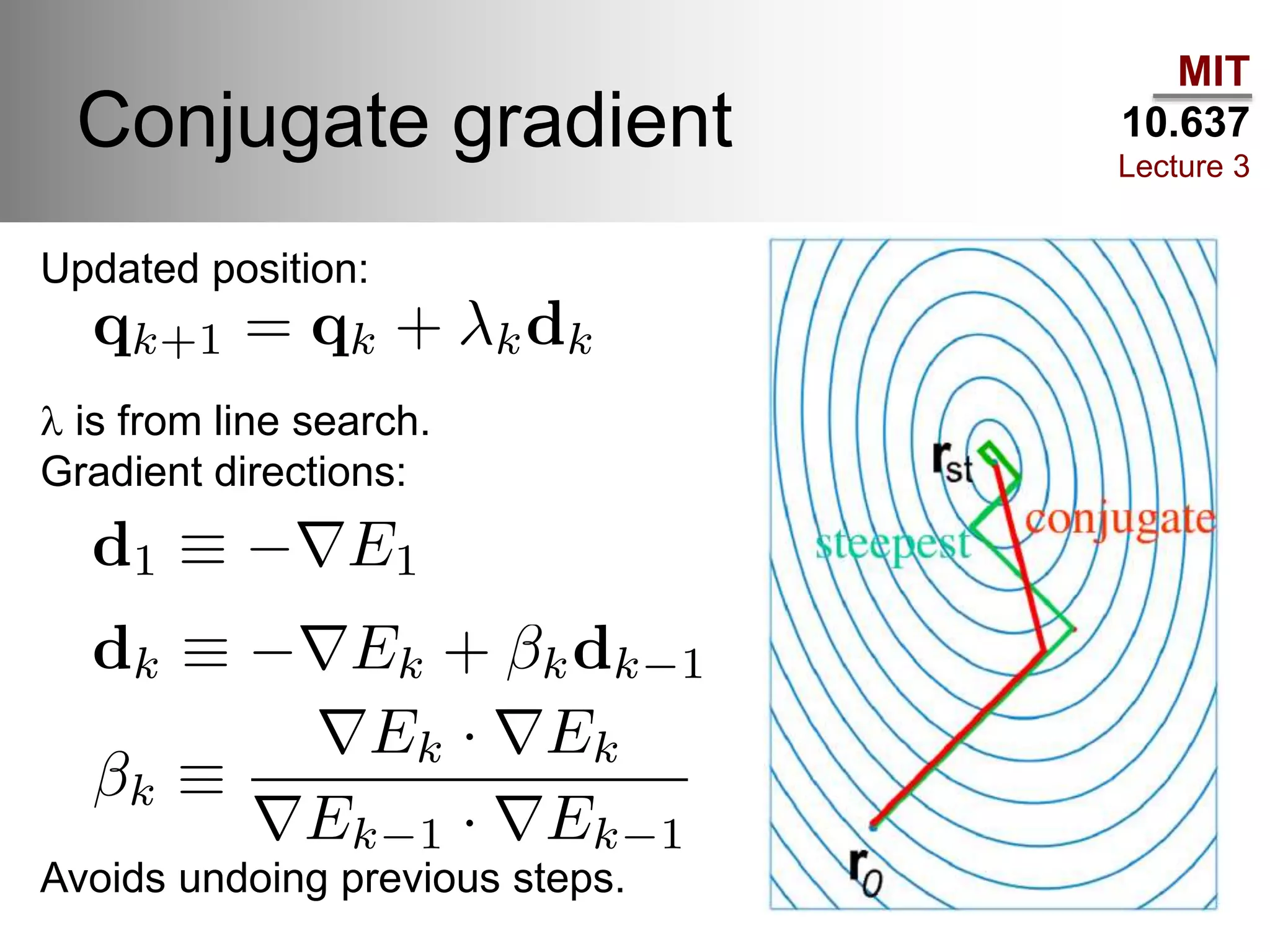

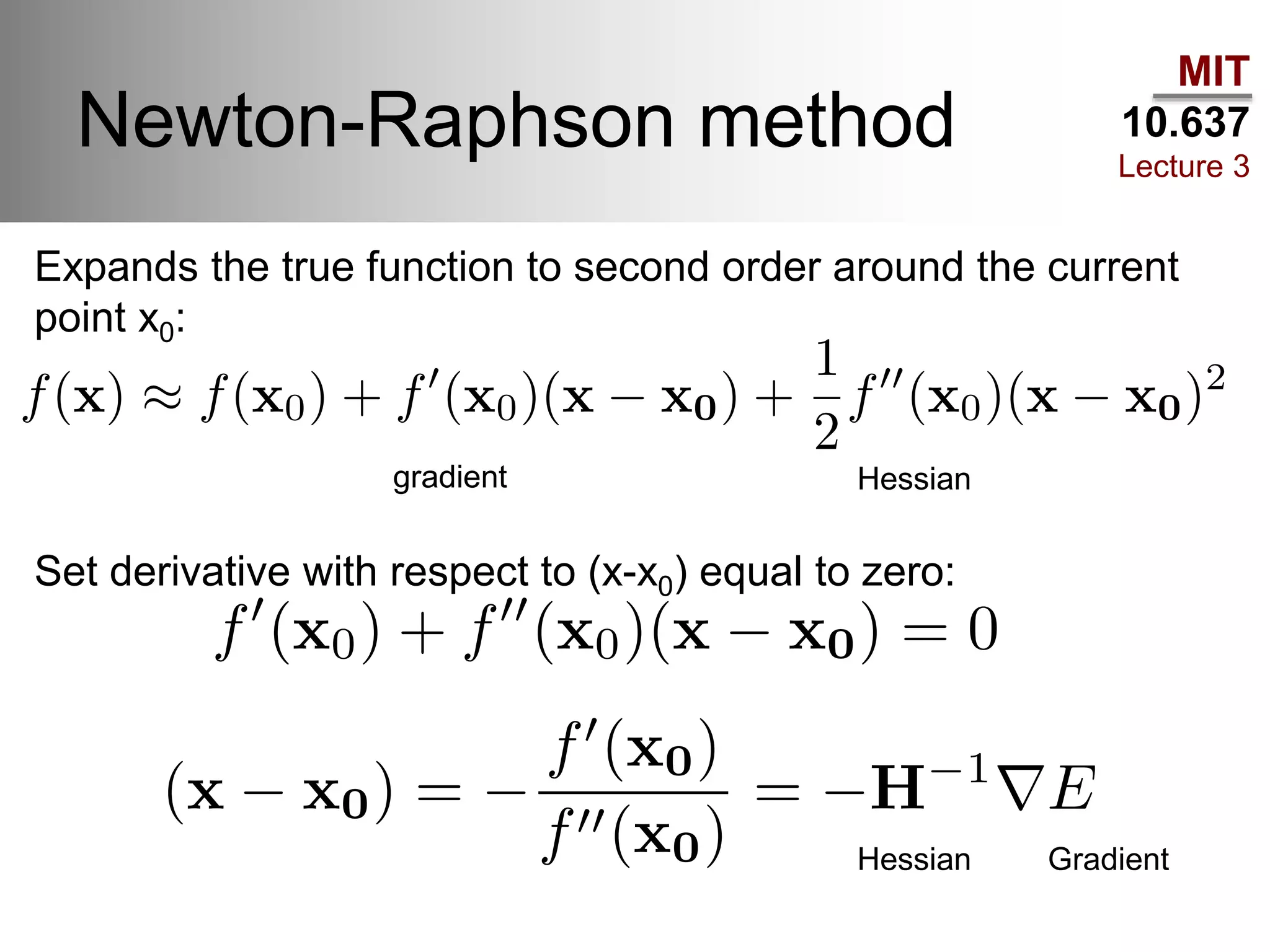

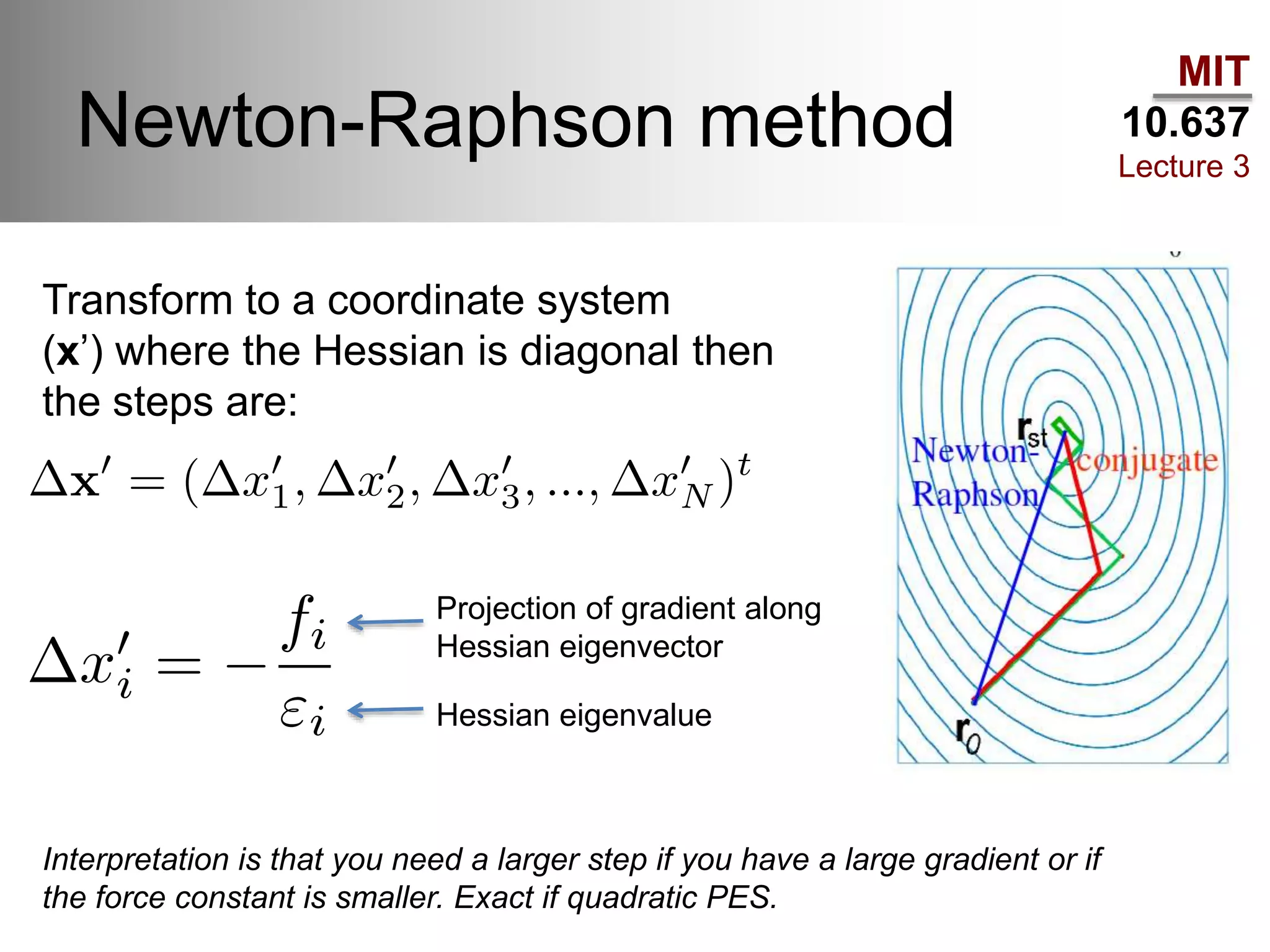

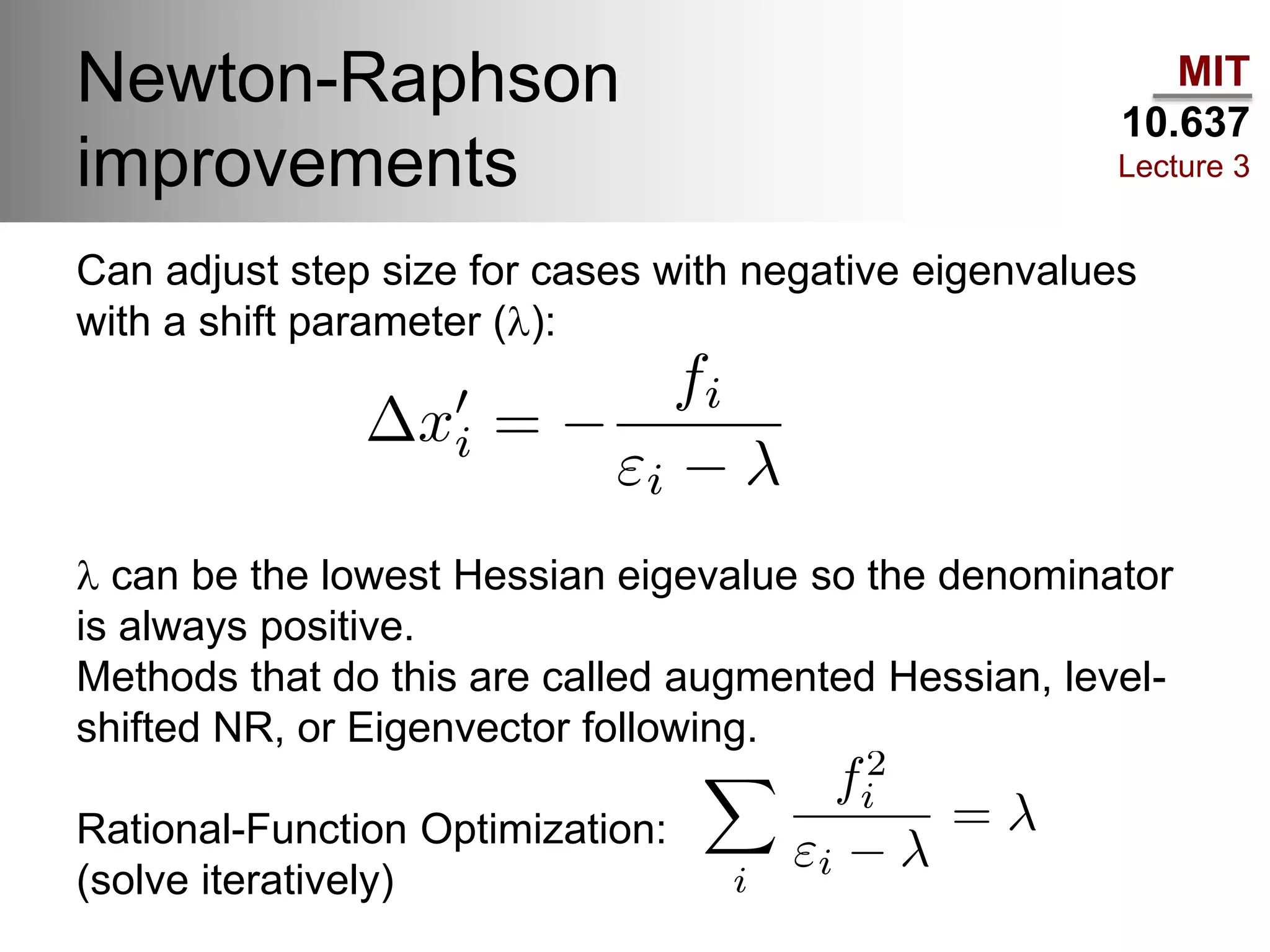

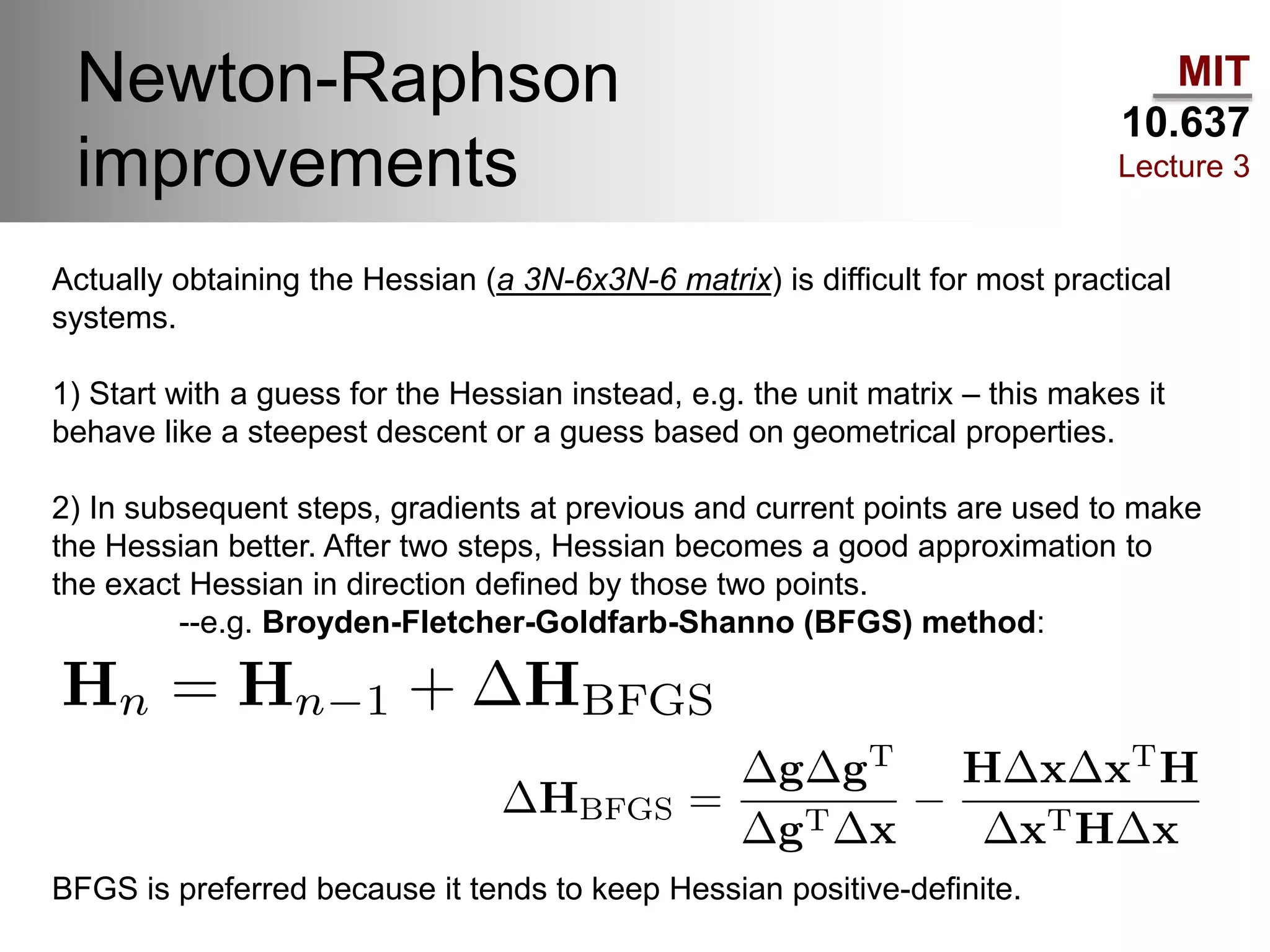

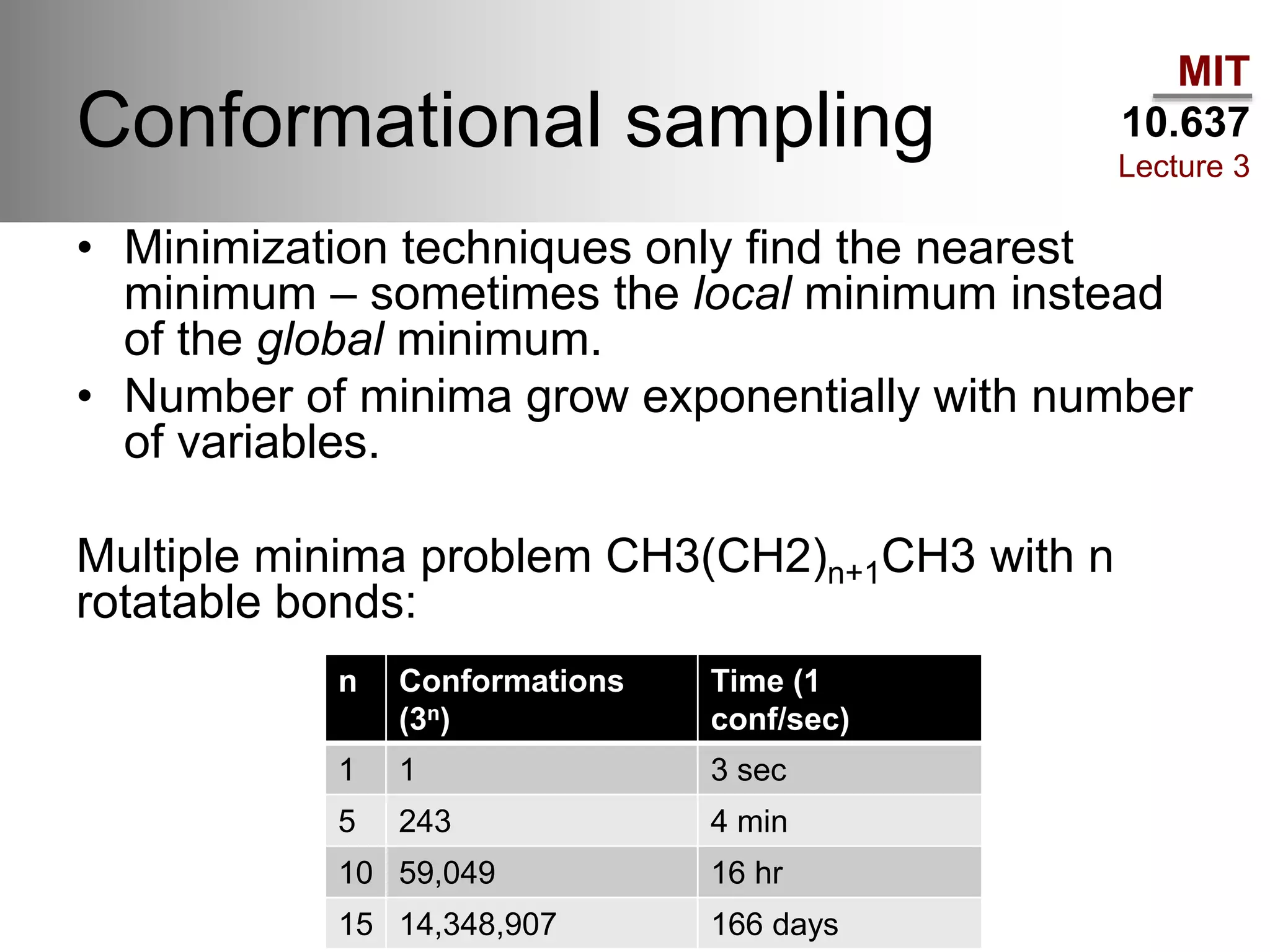

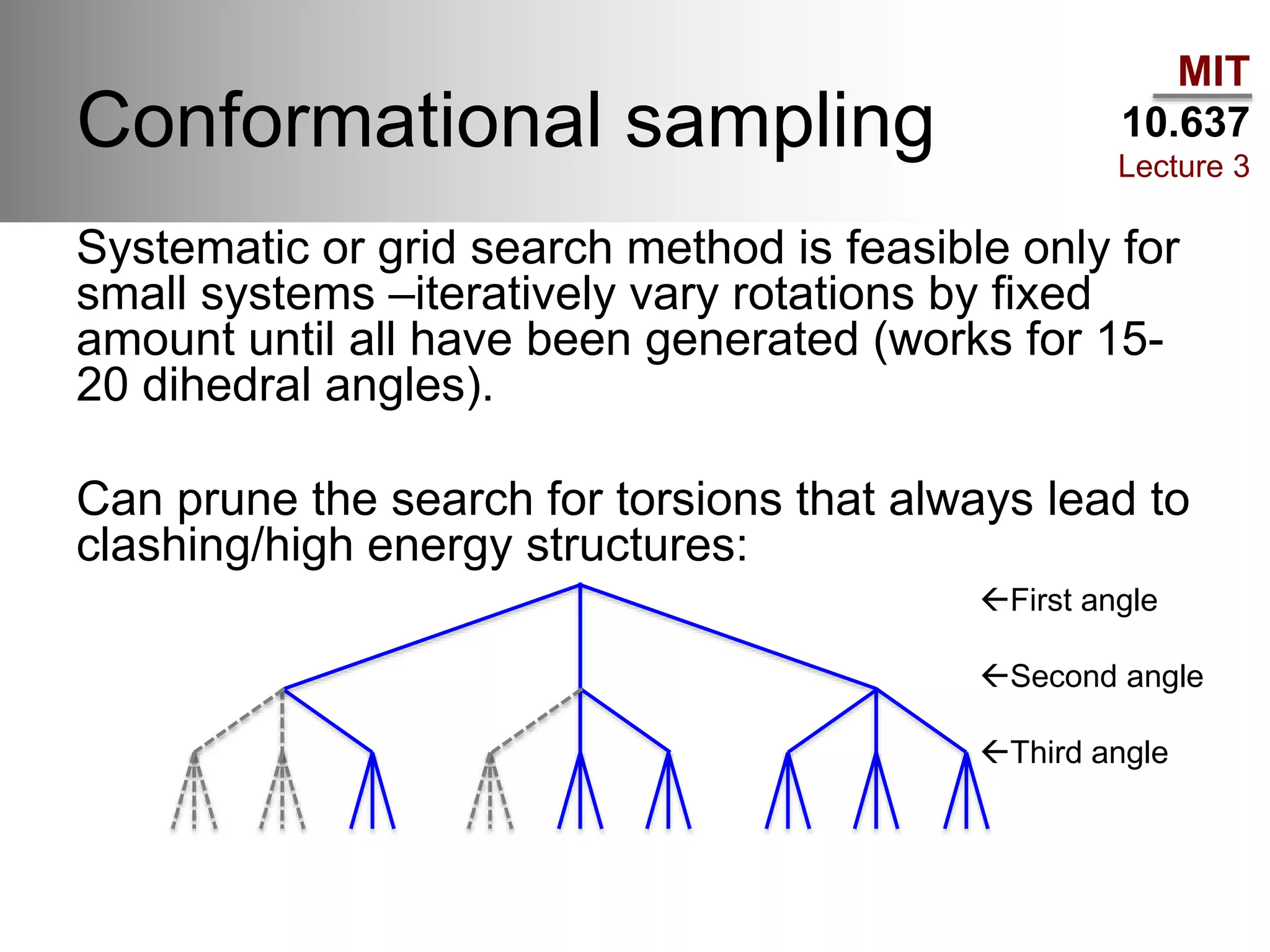

The document outlines the principles of potential energy surfaces (PES) in molecular geometry optimizations, discussing the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, the separation of variables, and various methods for PES mapping. It covers optimization techniques such as steepest descent, conjugate gradient, and Newton-Raphson methods, including their advantages, challenges, and improvements. Additionally, it addresses conformational sampling methods like Monte Carlo, molecular dynamics, and genetic algorithms, highlighting their applications in exploring the energy landscape of molecular systems.