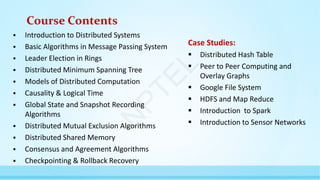

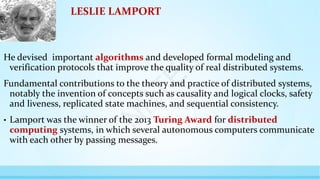

The document provides an introduction to distributed systems, highlighting their complexity due to asynchrony, partial failures, and the need for coordination among independent computing entities. It outlines the properties, challenges, and algorithms fundamental to distributed systems, illustrating their applications in various fields such as peer-to-peer computing and sensor networks. The lecture emphasizes the importance of understanding distributed computing principles to address real-world problems effectively.

![Modeling Processors and Channels

inbuf[1]

p1's local

variables

outbuf[1] inbuf[2]

outbuf[2]

p2's local

variables

Pink area (local vars + inbuf) is accessible state

for a processor.

N

P

T

E

L](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/w1lecturenotes-240912173604-48b9aa23/85/W1_Lecture-Notes-nptel-Distributed-system-38-320.jpg)

![Vector Time

•The system of vector clocks was developed independently by Fidge,

Mattern and Schmuck.

•In the system of vector clocks, the time domain is represented by a set of

n-dimensional non-negative integer vectors.

•Each process pi maintains a vector vti [1..n], where vti [i ] is the local

logical clock of pi and describes the logical time progress at process pi.

•vti [j ] represents process pi ’s latest knowledge of process pj local time.

•If vti [j ]=x , then process pi knows that local time at process pj has

progressed till x .

•The entire vector vti constitutes pi ’s view of the global logical time and is

used to timestamp events.

N

P

T

E

L](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/w1lecturenotes-240912173604-48b9aa23/85/W1_Lecture-Notes-nptel-Distributed-system-146-320.jpg)

![Vector Time

Process pi uses the following two rules R1 and R2 to update its clock:

R1: Before executing an event, process pi updates its local logical time as follows:

vti [i ] := vti [i ] + d (d > 0)

R2: Each message m is piggybacked with the vector clock vt of the sender process

at sending time. On the receipt of such a message (m,vt), process pi executes the

following sequence of actions:

•Update its global logical time as follows:

1 ≤ k ≤ n : vti [k] := max (vti [k], vti k])

•Execute R1

•Deliver the message m

N

P

T

E

L](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/w1lecturenotes-240912173604-48b9aa23/85/W1_Lecture-Notes-nptel-Distributed-system-147-320.jpg)

![Vector Time

•The timestamp of an event is the value of the vector clock of its process

when the event is executed.

•Figure 4.3 shows an example of vector clocks progress with the increment

value d=1.

•Initially, a vector clock is [0, 0, 0, ...., 0].

N

P

T

E

L](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/w1lecturenotes-240912173604-48b9aa23/85/W1_Lecture-Notes-nptel-Distributed-system-148-320.jpg)

![Comparing Vector Time Stamps

•The following relations are defined to compare two vector timestamps, vh and vk :

• If the process at which an event occurred is known, the test to compare two

timestamps can be simplified as follows: If events x and y respectively occurred at

processes pi and pj and are assigned timestamps vh and vk, respectively, then

x → y⇔ vh[i ] ≤ vk[i ]

x || y ⇔ vh[i ] > vk[i]∧vh[j ] < vk[j ]

vh = vk ⇔ ∀x : vh[x ] = vk [x ]

vh ≤ vk ⇔ ∀x : vh[x ] ≤ vk [x ]

vh < vk ⇔ vh ≤ vk and ∃x : vh[x ] < vk [x ]

vh || vk ⇔ ¬(vh < vk ) ∧ ¬(vk < vh)

N

P

T

E

L](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/w1lecturenotes-240912173604-48b9aa23/85/W1_Lecture-Notes-nptel-Distributed-system-150-320.jpg)

![Properties of Vector Time

Strong Consistency

• The system of vector clocks is strongly consistent; thus, by examining the vector

timestamp of two events, we can determine if the events are causally related.

• However, Charron-Bost showed that the dimension of vector clocks cannot be less

than n, the total number of processes in the distributed computation, for this

property to hold.

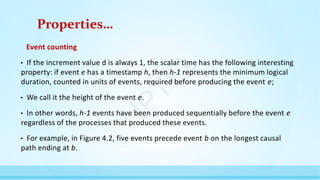

Event Counting

• If d=1 (in rule R1), then the i th component of vector clock at process pi , vti [i ],

denotes the number of events that have occurred at pi until that instant.

• So, if an event e has timestamp vh, vh[j ] denotes the number of events executed by

process pj that causally precede e. Clearly, ∑ vh[j ]− 1 represents the total number

of events that causally precede e in the distributed computation.

N

P

T

E

L](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/w1lecturenotes-240912173604-48b9aa23/85/W1_Lecture-Notes-nptel-Distributed-system-152-320.jpg)