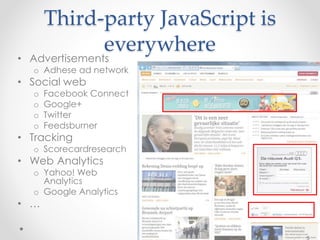

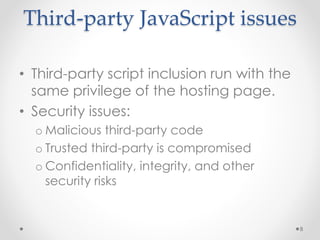

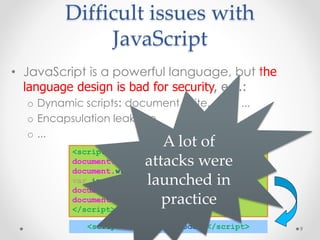

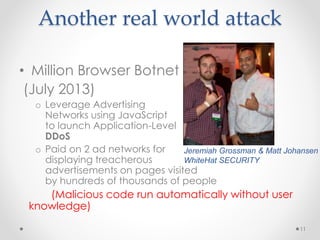

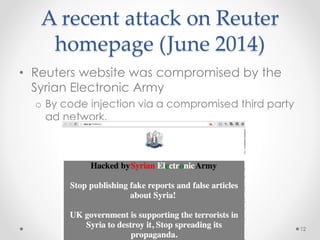

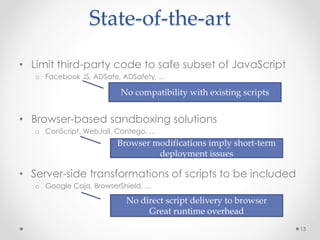

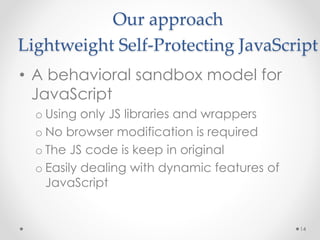

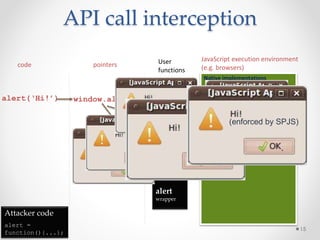

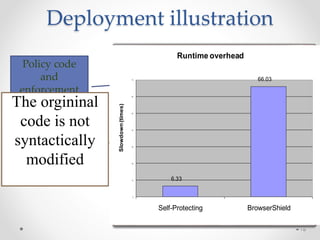

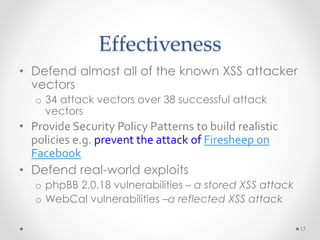

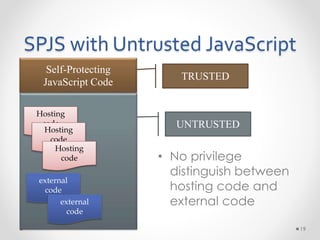

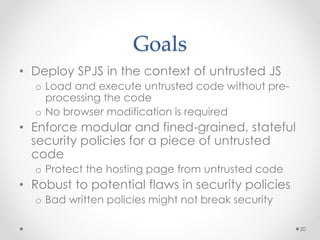

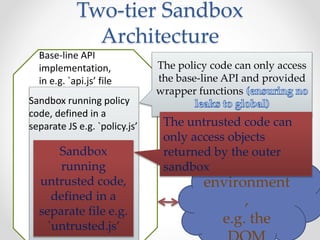

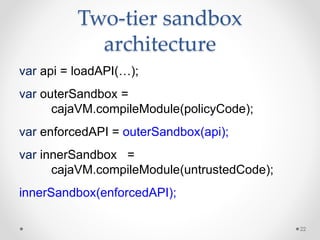

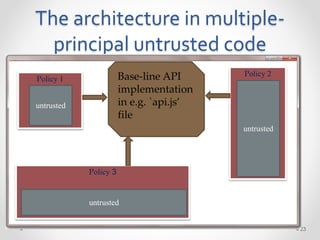

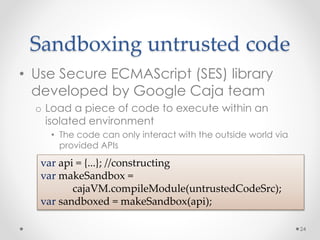

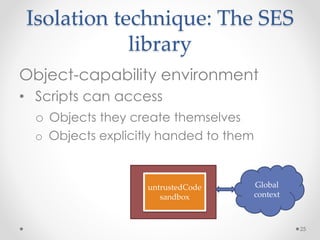

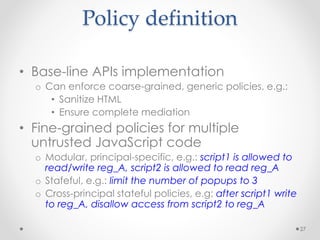

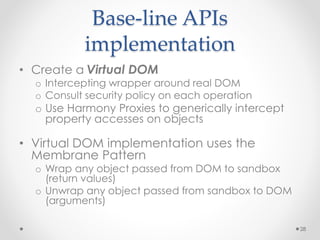

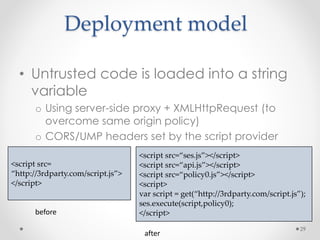

This document summarizes a seminar on securing untrusted web content at browsers. It discusses how 92% of websites use JavaScript, which can pose security issues if third-party scripts are malicious or compromised. The seminar presents an approach using lightweight self-protecting JavaScript that enforces security policies without browser modifications. This is done by sandboxing untrusted code execution and intercepting API calls according to enforcement rules defined in policy files. Real-world attacks are also examined that were carried out by injecting malicious code into third-party scripts on major websites.

![92% of all websites use

JavaScript [w3techs.com]

3

“88.45% of the Alexa top 10,000

web sites included at least one

remote JavaScript library”

CCS’12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phuacmchicago-140910232007-phpapp02/85/Web-security-Securing-Untrusted-Web-Content-in-Browsers-3-320.jpg)