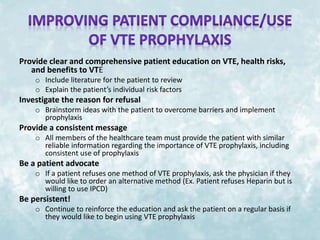

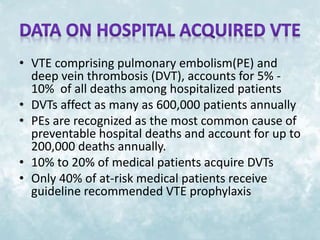

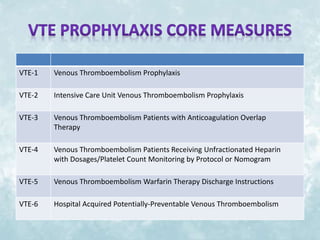

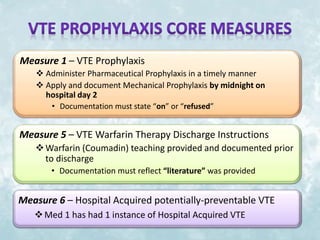

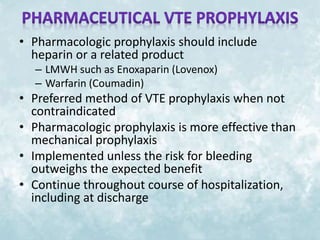

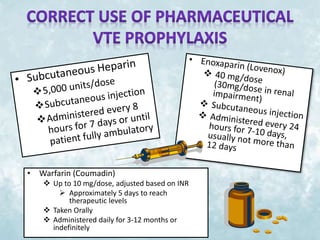

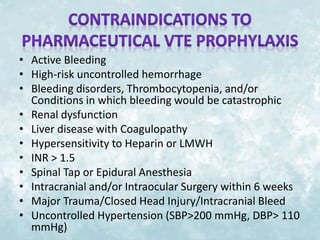

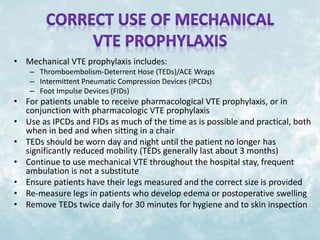

This document discusses venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis for medical patients in the hospital. It covers the importance and impact of VTE, guidelines and measures for VTE prophylaxis, types and use of pharmaceutical and mechanical VTE prophylaxis, contraindications, and ways to improve patient compliance. The goal is to understand how to properly apply VTE prophylaxis to reduce preventable hospital deaths from VTE events like pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis.

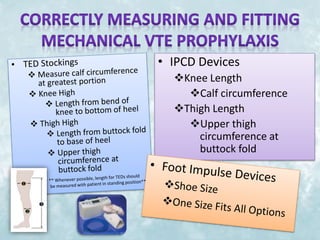

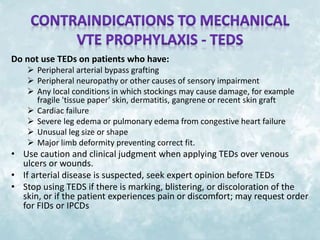

![Do not use IPCDS on patients who have:

Any local leg condition in which the sleeves may interfere, such as:

dermatitis,

vein ligation [immediate postoperative]

gangrene,

recent skin graft.

Severe arteriosclerosis or other ischemic vascular disease.

Massive edema of the legs or pulmonary edema from congestive heart

failure

Extreme deformity of the leg

Suspected pre-existing deep venous thrombosis

Do not use FIDs on patients who have:

Conditions where an increase of fluid to the heart may be detrimental

Congestive Heart Failure

Pre-existing deep vein thrombosis, thrombophlebitis or pulmonary

embolism](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vteprophylaxiscderamos-141209202906-conversion-gate01/85/Vte-prophylaxis-14-320.jpg)