This document outlines a presentation on using virtual machine forking and memory replay techniques for malware fuzzing and behavior modeling. Key points include:

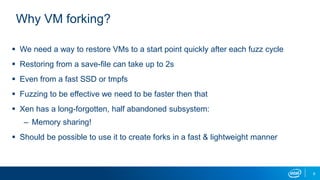

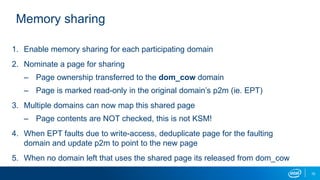

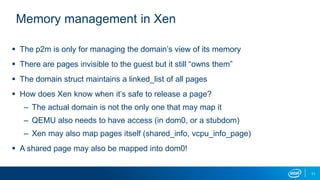

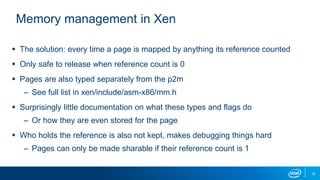

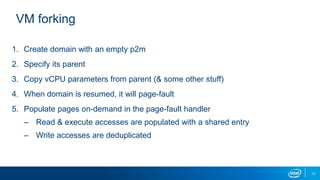

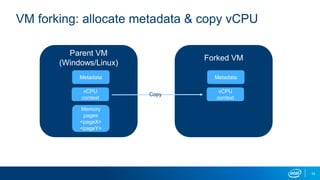

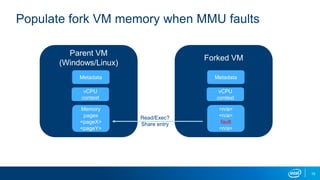

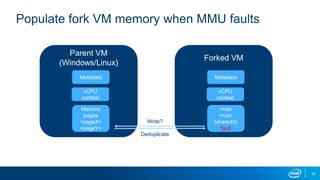

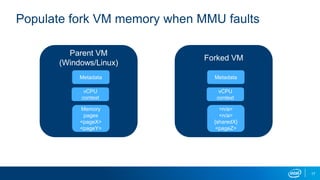

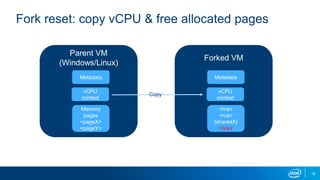

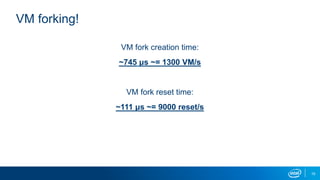

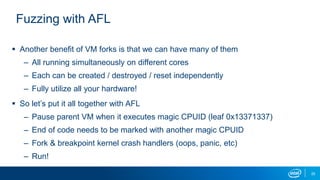

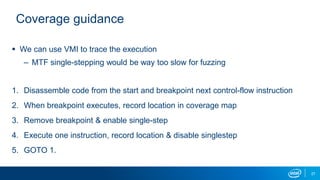

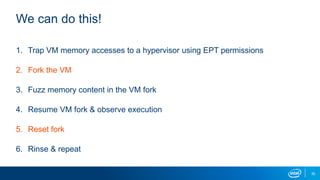

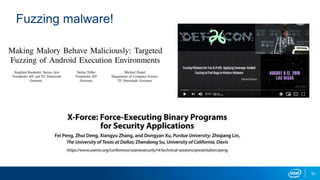

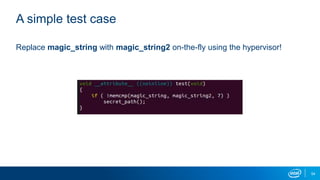

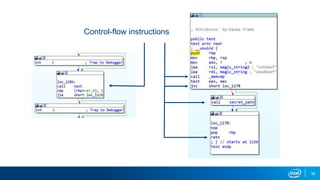

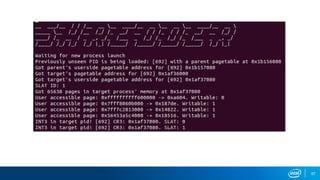

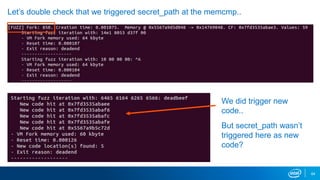

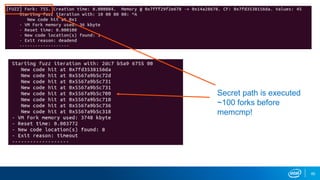

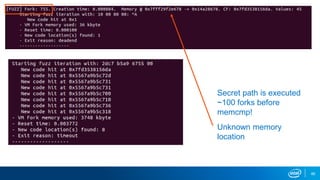

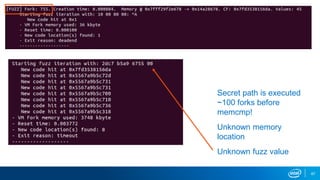

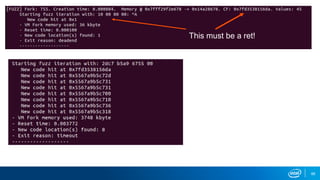

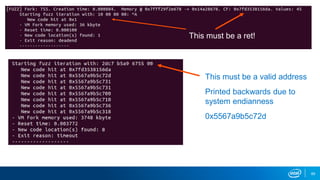

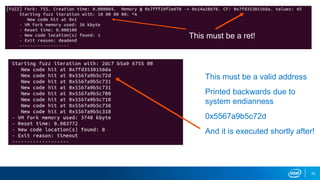

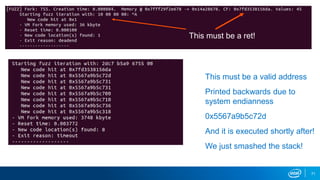

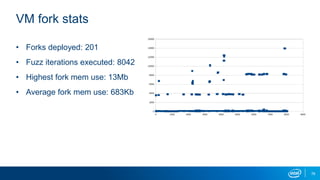

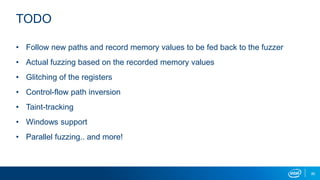

- VM forking allows quickly resetting VMs for fuzzing by sharing and duplicating memory pages between forks. This enables high throughput fuzzing.

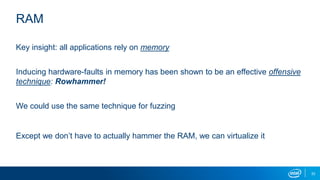

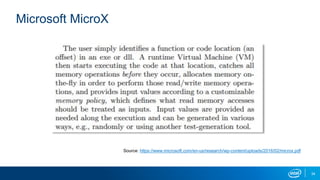

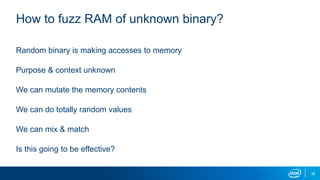

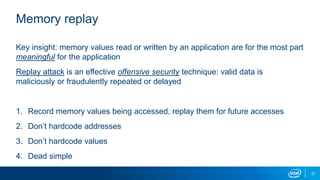

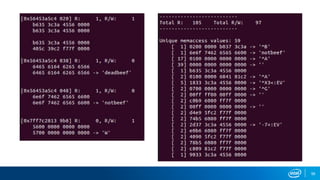

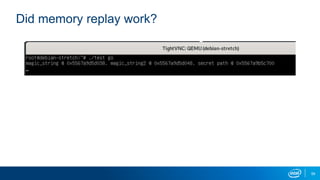

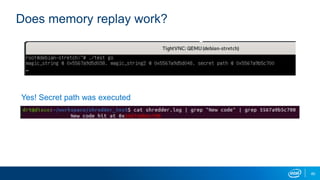

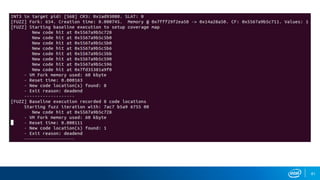

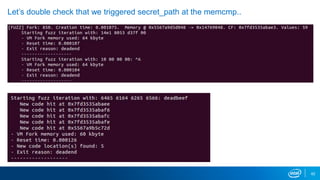

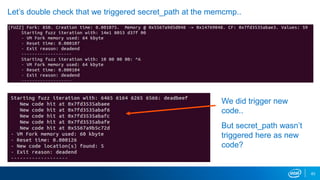

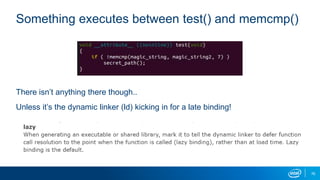

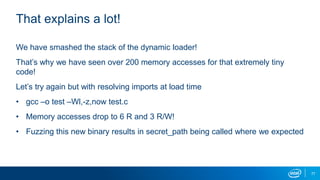

- Memory replay replays recorded memory values accessed by an application to induce faults, as an alternative to random fuzzing which may not be effective.

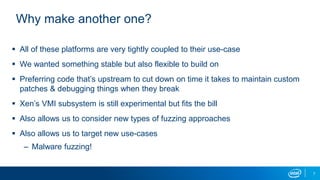

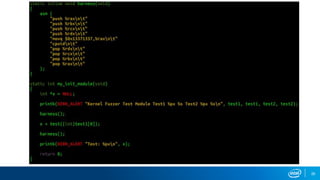

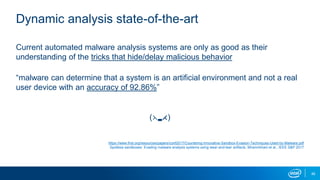

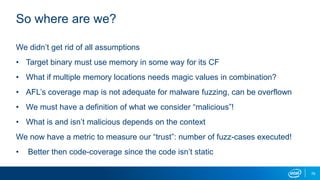

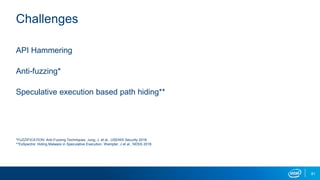

- These techniques were implemented in proof-of-concept tools to demonstrate fuzzing unknown binaries and building behavior models without assumptions about malware tricks or payloads.

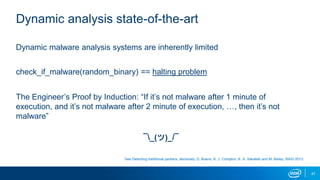

- The goal is to dynamically analyze malware without limitations of traditional analysis systems and gain insights into prevalent attack