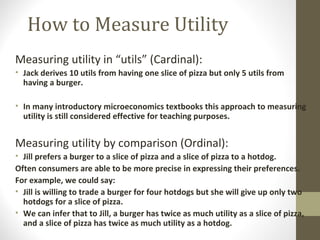

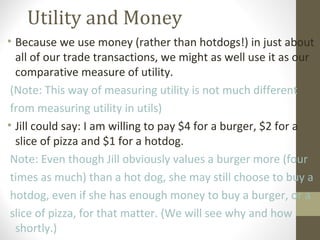

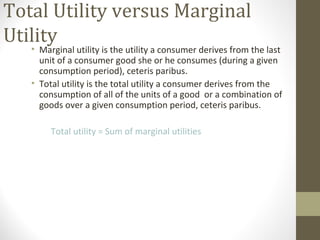

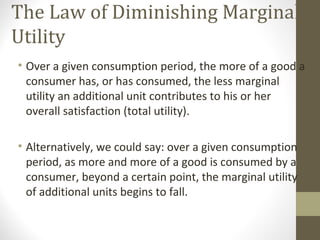

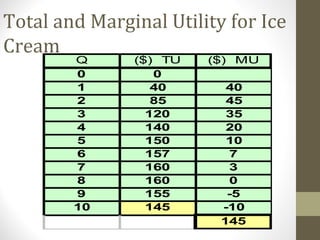

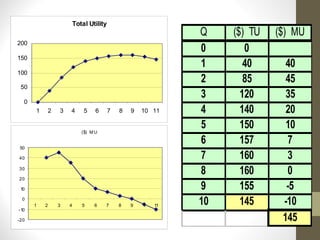

The document discusses consumer theory and how consumers make choices given income constraints. It defines utility as the satisfaction derived from consuming goods and services. Consumers aim to maximize utility within their budgets by comparing the marginal utility of goods. Marginal utility diminishes as consumption of a good increases. The document provides examples to illustrate total utility, marginal utility, and how consumers determine optimal consumption levels of different goods based on marginal utility comparisons and income constraints.