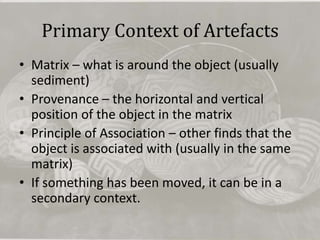

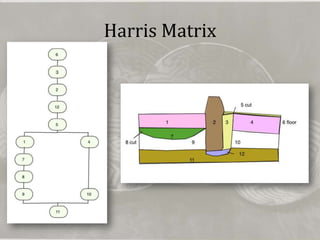

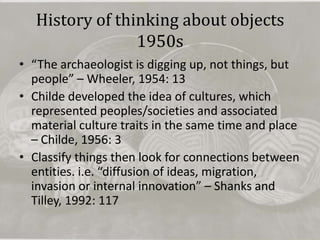

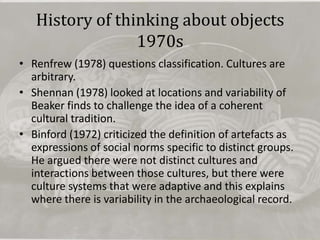

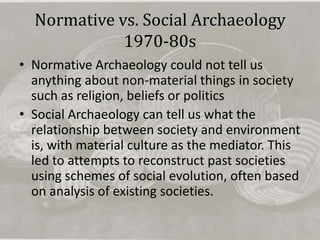

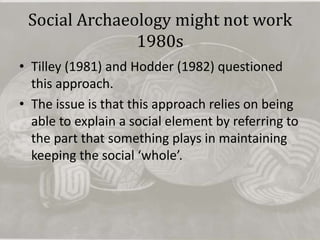

This document discusses the analysis and interpretation of archaeological artifacts. It defines an artifact as any object made or modified by humans. Archaeologists examine the primary context of artifacts, including the surrounding matrix and their horizontal and vertical positions. Formation processes, both cultural and natural, help explain how objects became buried. Dating artifacts can involve spot dating during excavation or post-excavation methods like absolute or relative dating. The document traces the history of how archaeologists have approached and interpreted artifacts, from classifying cultures based on material traits to more nuanced social archaeological approaches that aim to reconstruct past societies.