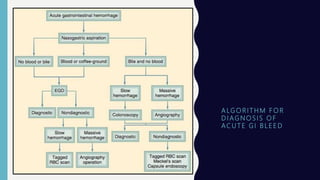

1) UGI bleeding arises from the GI tract proximal to the ligament of Treitz and accounts for 80% of significant GI hemorrhage.

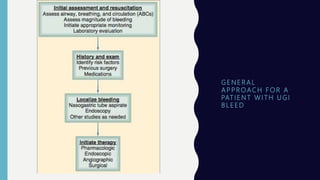

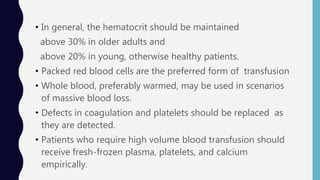

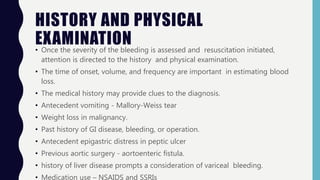

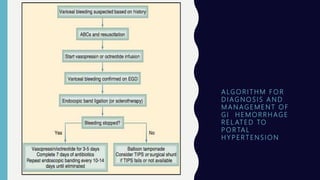

2) Initial assessment of a patient with UGI bleed includes ABCs, hemodynamic status, and hematocrit which is not useful in acute setting.

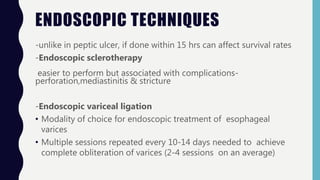

3) Peptic ulcer disease is the most common cause of non-variceal upper GI bleeding, accounting for 40% of cases. Endoscopic management is first-line treatment.