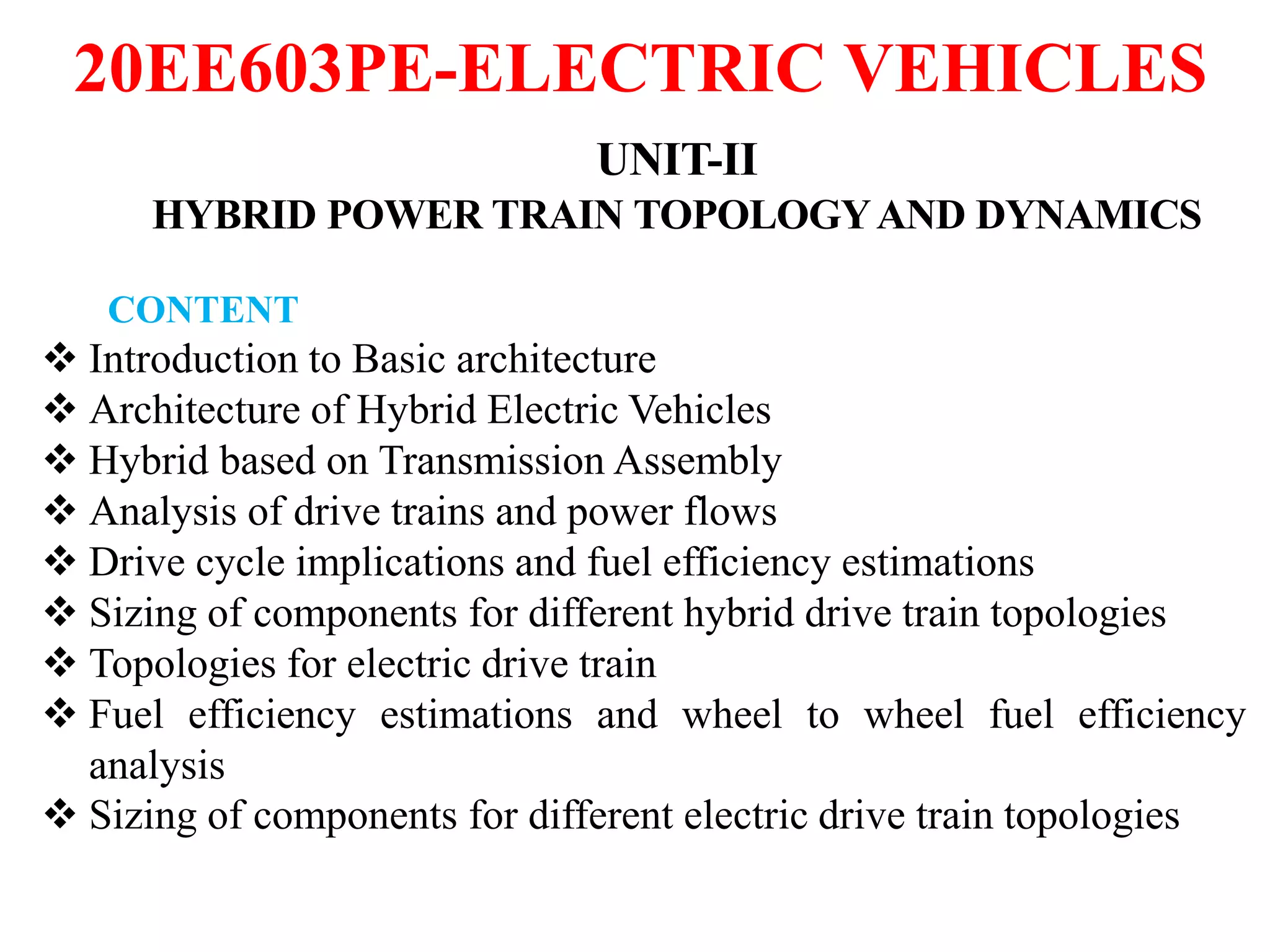

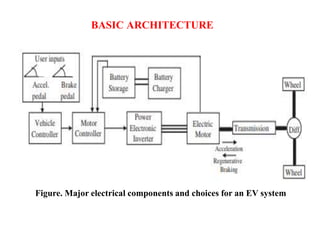

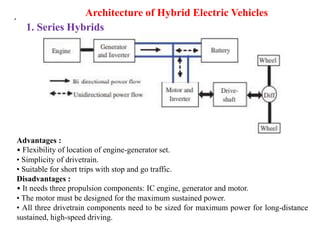

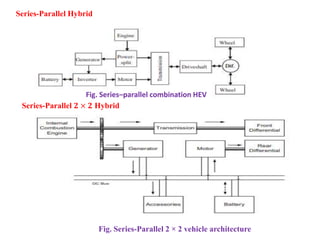

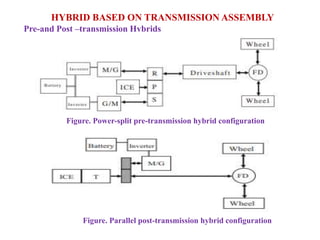

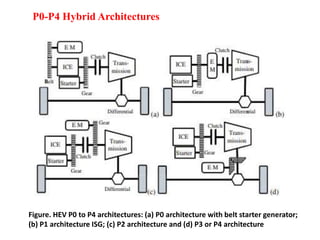

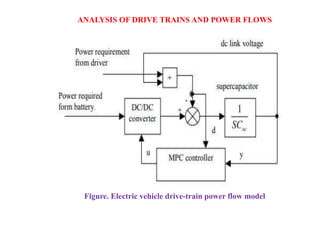

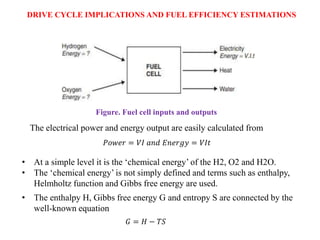

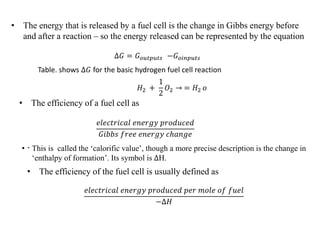

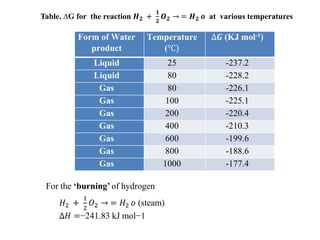

This document discusses hybrid powertrain topologies and dynamics. It describes different hybrid electric vehicle architectures including series, parallel, and series-parallel hybrids. It also discusses hybrid systems based on the transmission assembly, including pre-transmission and post-transmission hybrids. The document analyzes drive train power flows and explores implications for fuel efficiency estimations based on drive cycles. It examines sizing components for different hybrid and electric drive train topologies.