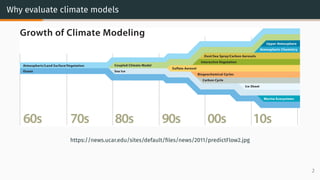

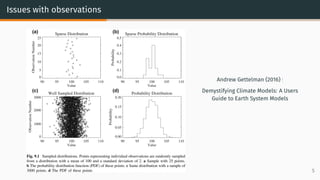

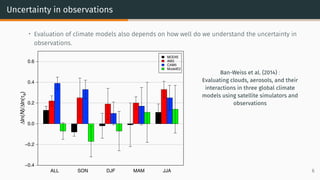

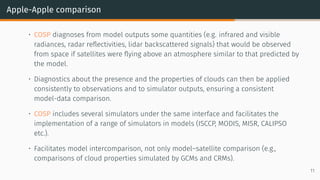

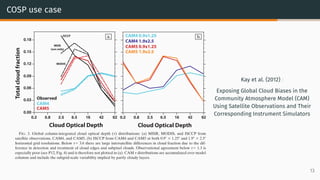

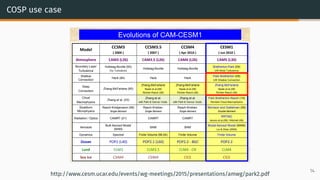

The document discusses model evaluation and validation. It introduces key concepts like evaluation, validation, and the apple-orange problem when directly comparing models and observations. It describes using a satellite simulator like COSP to facilitate apple-to-apple comparisons by simulating what satellites would observe from the model. The document also notes issues with observations like errors and uncertainties that must be considered during evaluation.