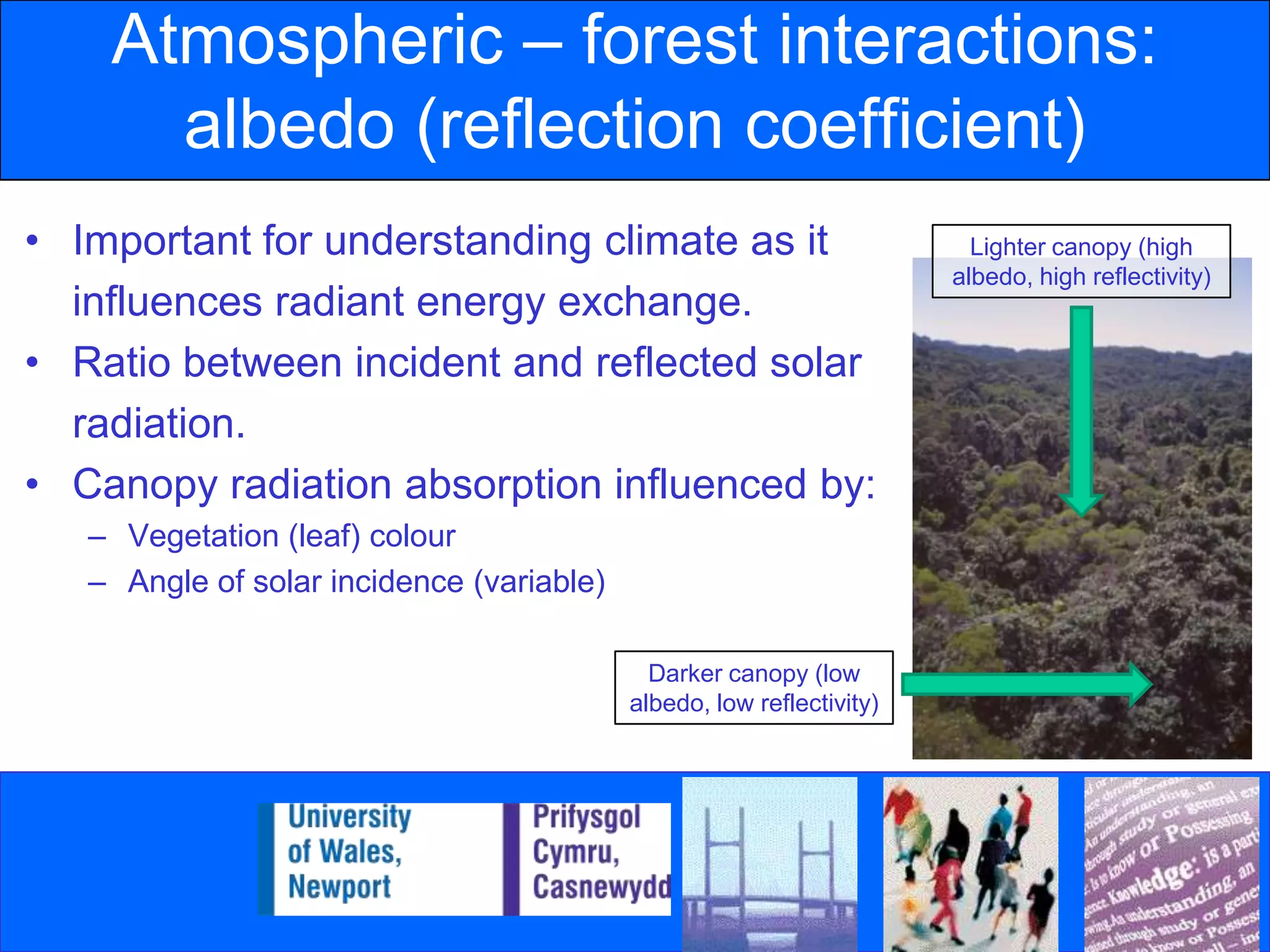

Tropical moist forests play a crucial role in atmospheric interactions, significantly influencing energy exchange through their low albedo and high evapotranspiration rates. Deforestation alters these interactions, leading to increased surface temperatures and reduced precipitation by affecting energy partitioning and atmospheric dynamics. Understanding these relationships is vital for comprehending the broader impacts of climate change and the importance of forest ecosystems.