The document provides information on traumatic brain injury (TBI):

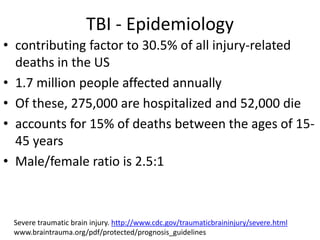

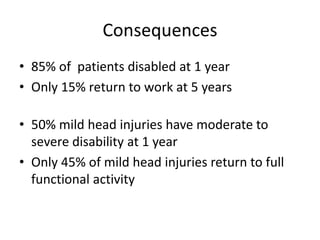

- TBI is defined as an insult to the brain from an external force, which can lead to temporary or permanent impairment. It affects over 1.7 million people annually in the US.

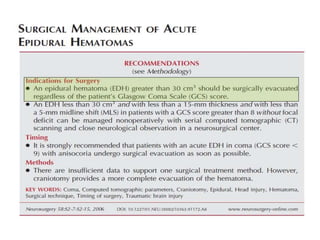

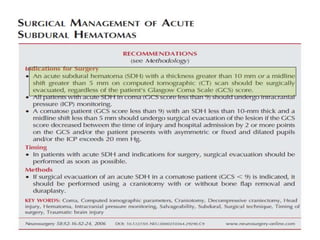

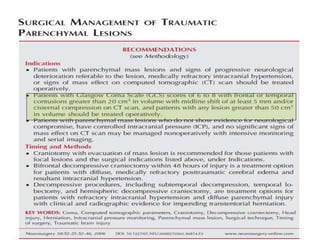

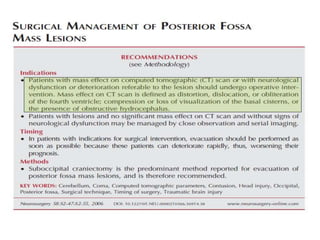

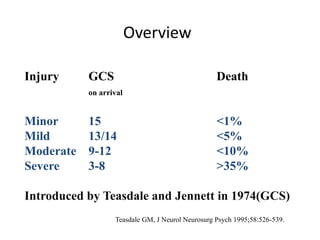

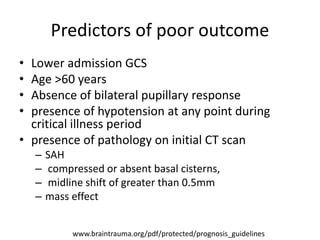

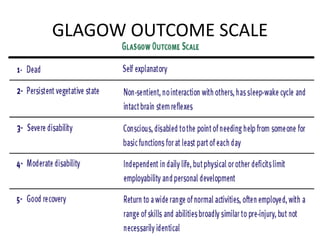

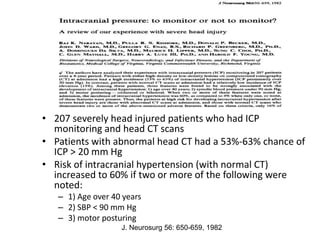

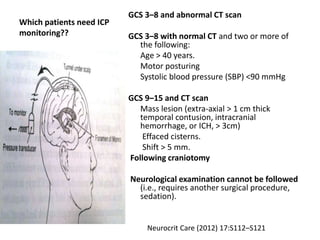

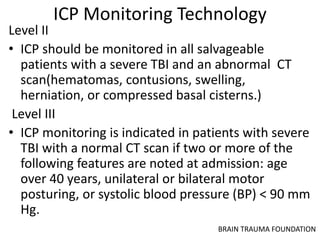

- Severity is classified using the Glasgow Coma Scale. More severe injuries have higher mortality rates. Predictors of poor outcome include lower GCS, age over 60, abnormal CT findings, and hypotension.

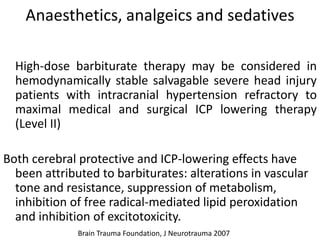

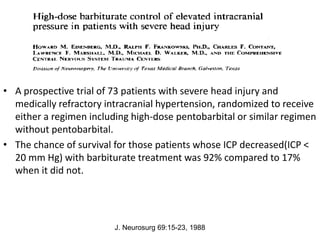

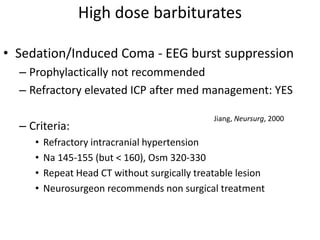

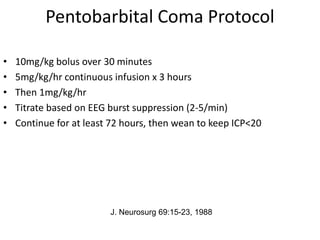

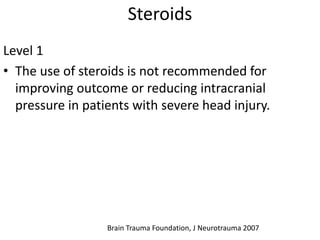

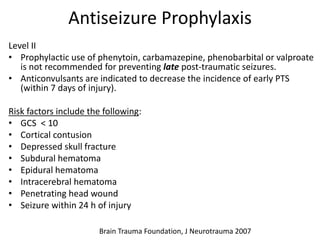

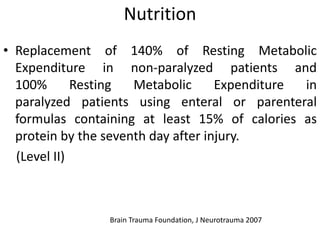

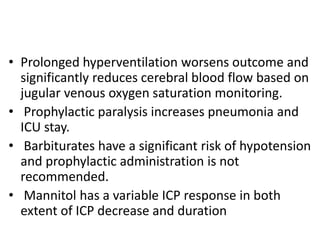

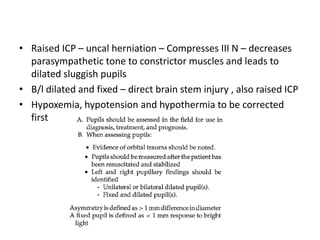

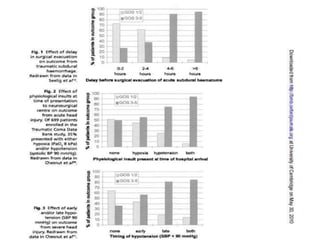

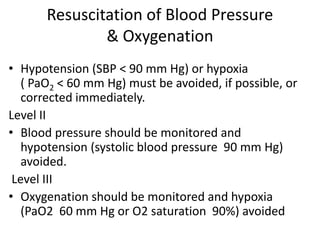

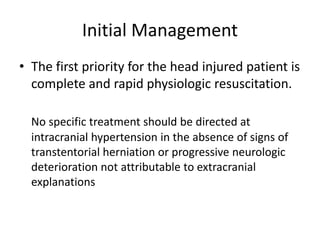

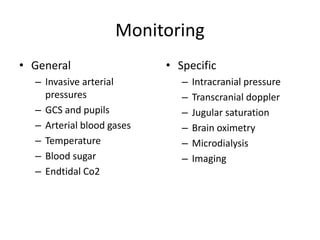

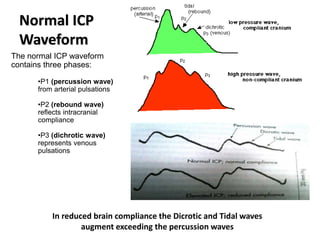

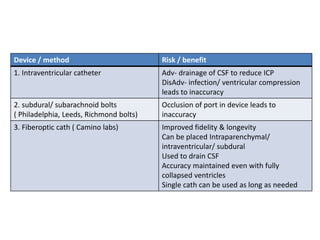

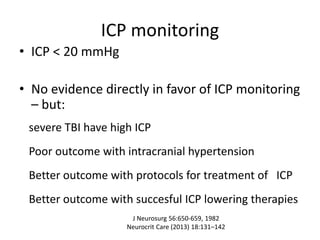

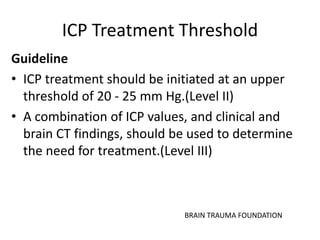

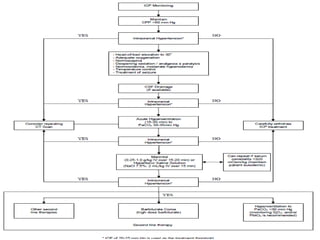

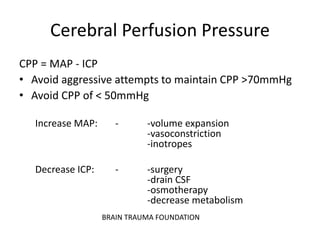

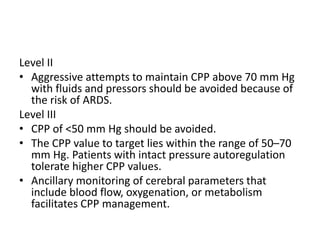

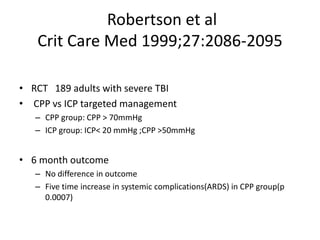

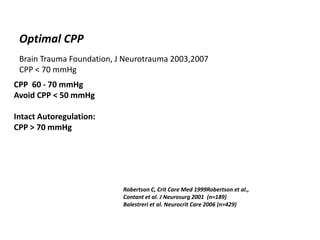

- Treatment aims to prevent secondary injury from hypotension, hypoxia, increased ICP, and includes monitoring vital signs, ICP, CPP, and providing interventions like osmotherapy, surgery, and medications to control ICP and maintain

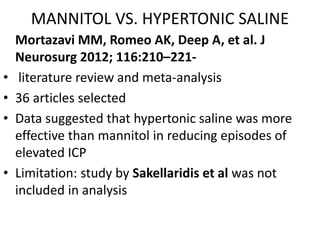

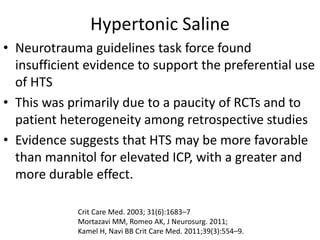

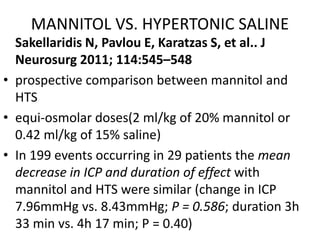

![MANNITOL VS. HYPERTONIC SALINE

Kamel H, Navi BB, Nakagawa K, et al. Crit Care Med

2011; 39:554–559

• a meta-analysis

• 5 trials comprising 112 patients with 184 episodes of

elevated ICP

• RR of ICP control favored HTS[1.16; 95% (CI) 1.00–

1.33], and the difference in ICP was only 2.0mmHg -

questionable clinical significance

authors conclusion

• HTS is more effective than mannitol for the treatment

of elevated ICP and suggest that hypertonic saline

may be superior to the current standard of care](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tbi-200829124817/85/Traumatic-brain-injury-anaesthetic-implication-58-320.jpg)