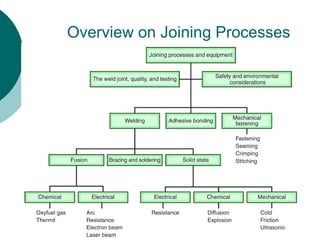

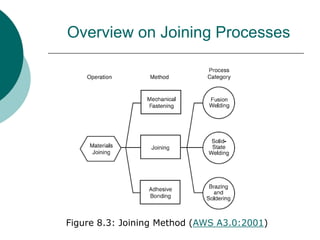

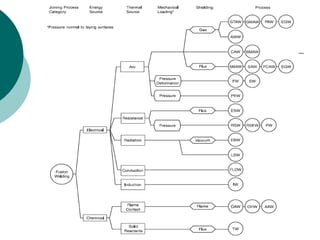

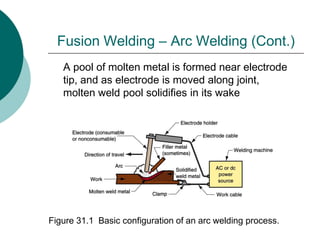

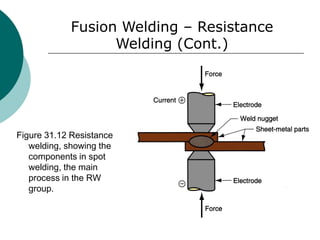

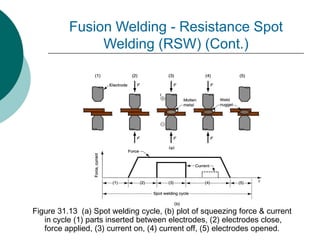

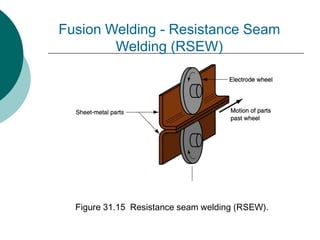

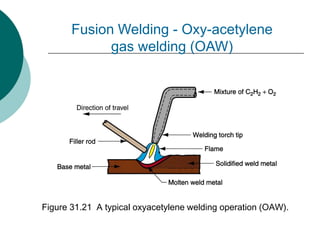

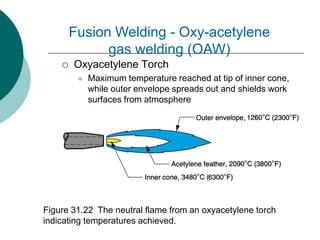

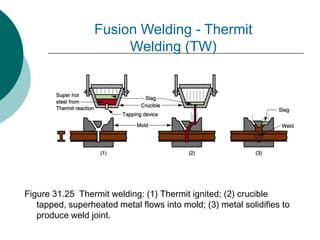

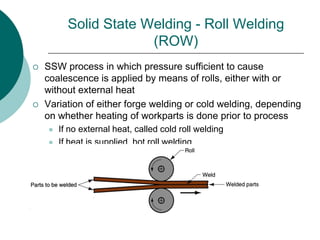

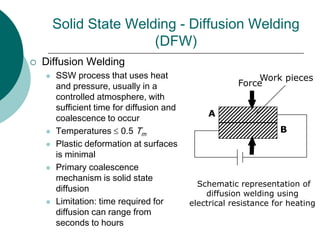

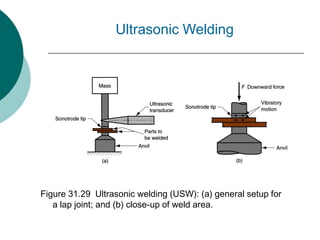

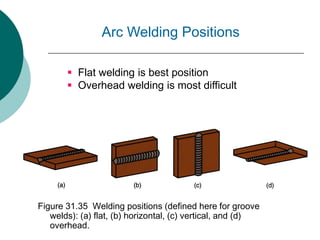

This document discusses various joining processes including welding, brazing, soldering, adhesive bonding, and mechanical fastening. It focuses on welding processes, describing fusion welding techniques like arc welding, resistance welding, oxyfuel welding, and others. For arc welding, it explains the basic configuration and different electrode and power source types. For resistance welding, it describes resistance spot welding and seam welding. The document also discusses solid state welding techniques that join materials without melting.