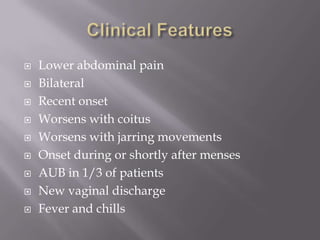

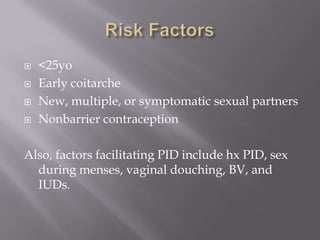

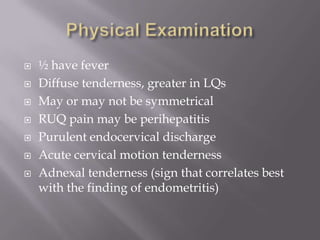

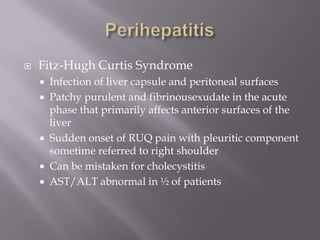

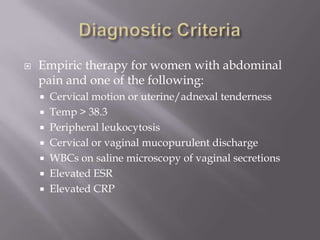

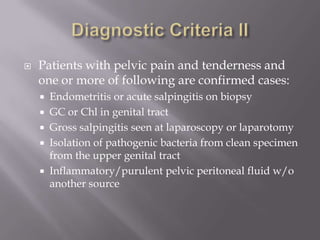

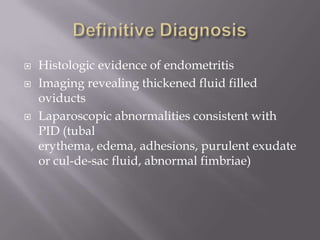

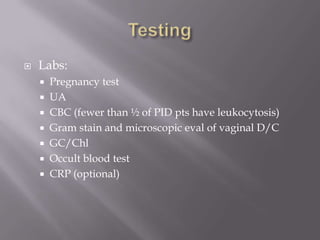

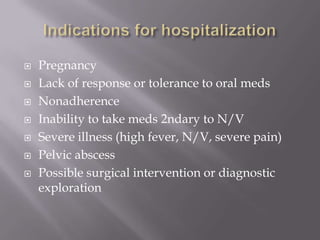

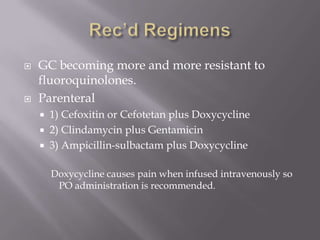

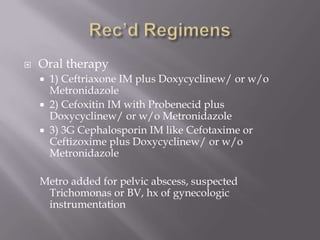

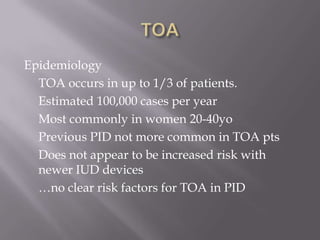

This document discusses pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA). PID is an infection of the female upper genital tract that is commonly caused by Chlamydia or gonorrhea. Symptoms include lower abdominal pain and tenderness. TOA occurs in about 1/3 of PID cases and appears on ultrasound as a cystic abdominal mass. Treatment involves antibiotics, with transvaginal drainage of large TOAs if medical therapy fails. Hospitalization is recommended if symptoms are severe or not improving with oral antibiotics alone.