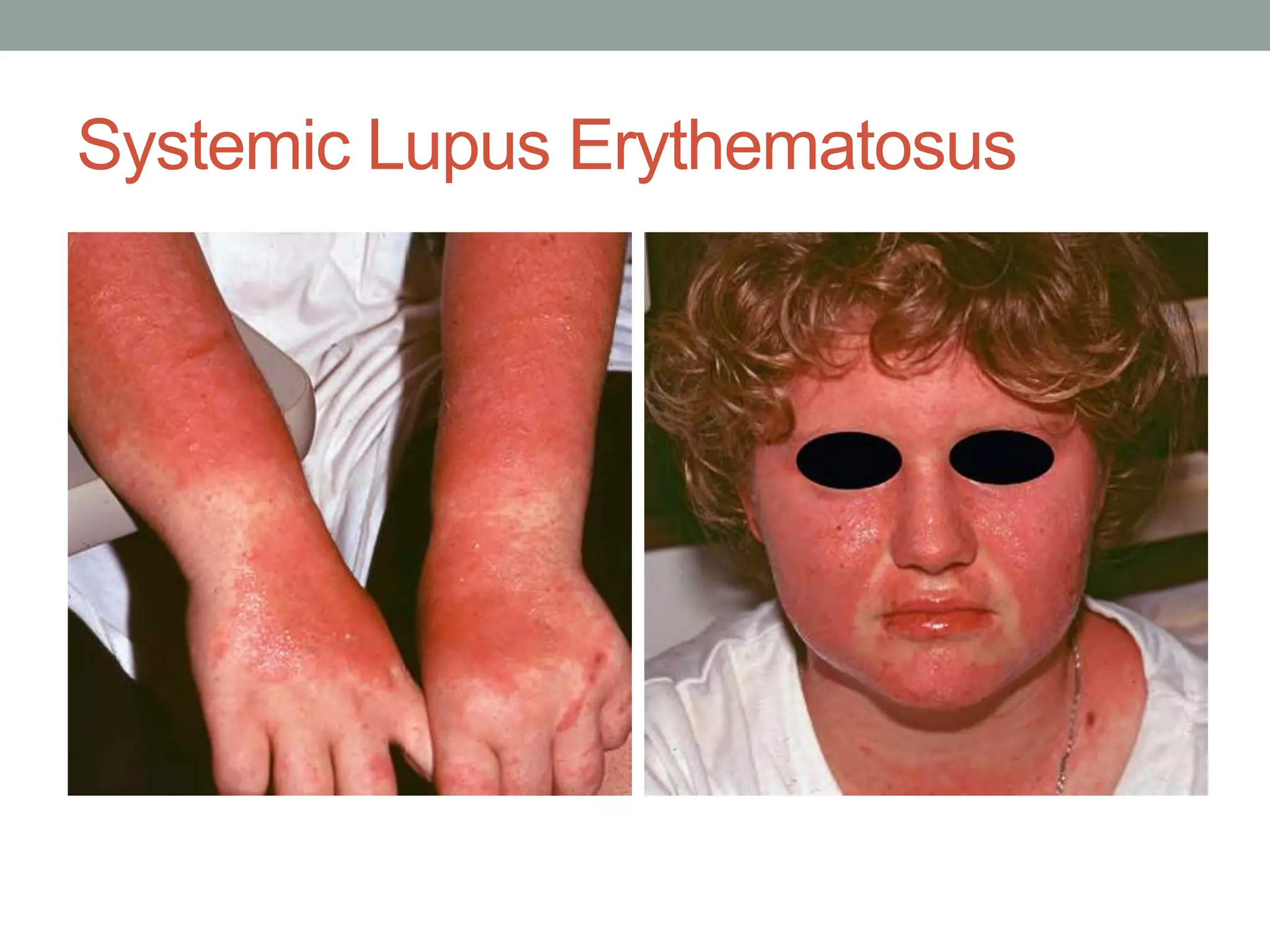

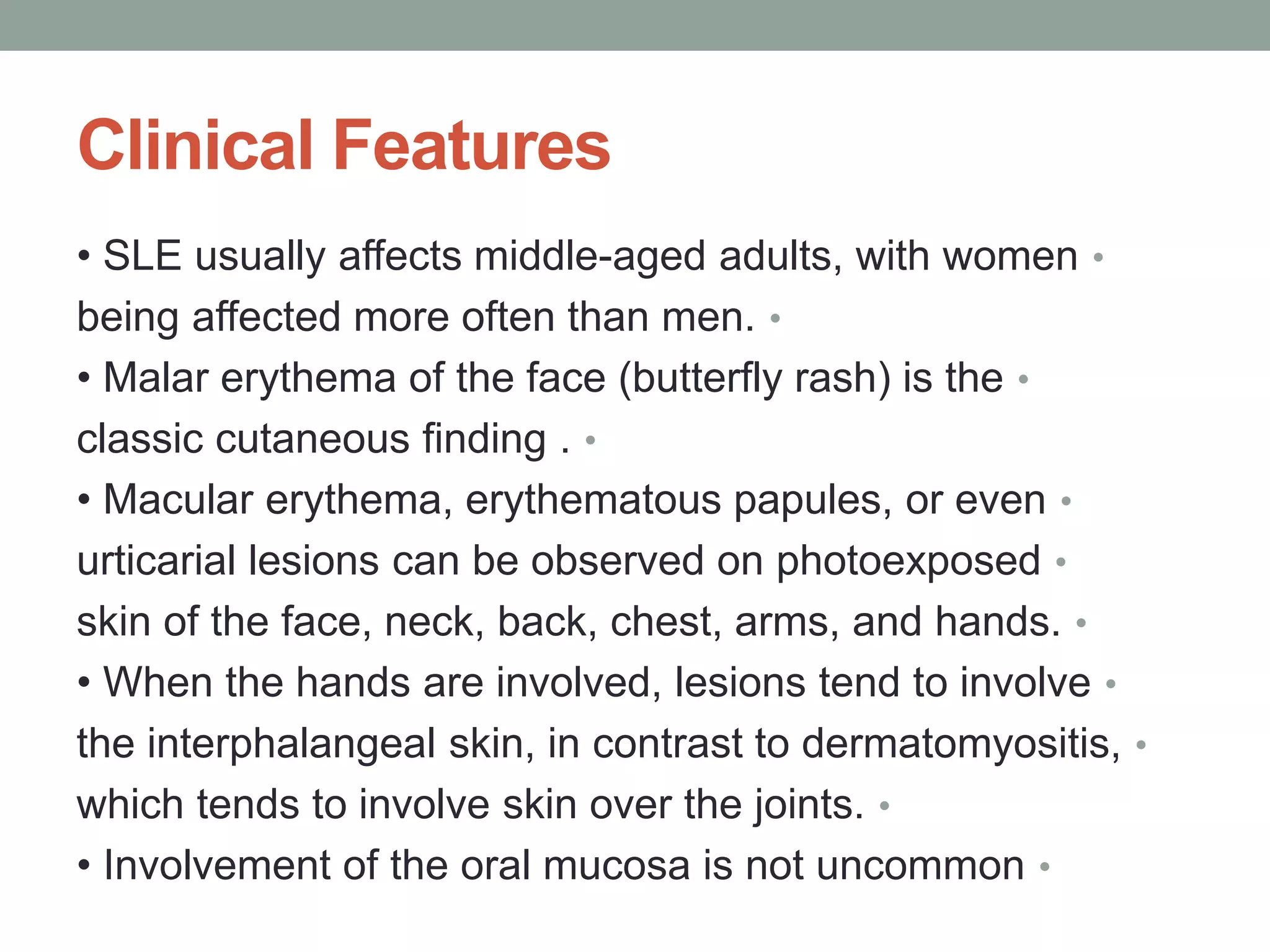

This document discusses three types of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). SLE is an autoimmune disorder characterized by autoantibodies against nuclear DNA. SCLE is a variant of lupus characterized by anti-Ro antibodies. DLE causes erythematous plaques and scarring, often affecting the face and ears. Treatment involves photoprotection, topical steroids, hydroxychloroquine and occasionally oral steroids depending on the severity of symptoms for each condition.