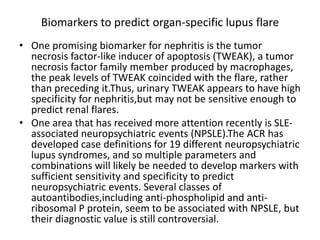

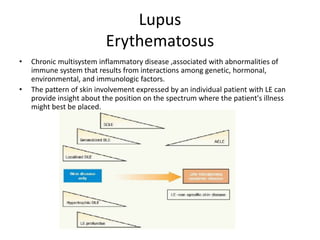

- Lupus erythematosus is a chronic inflammatory disease associated with abnormalities of the immune system that results from genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors interacting. It can involve the skin and multiple organ systems.

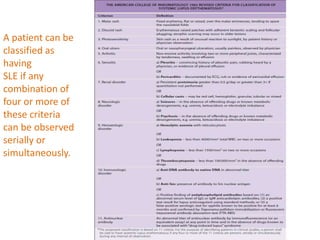

- The document discusses the history, epidemiology, etiology, pathogenesis, clinical findings and classification of the different types of cutaneous lupus erythematosus including acute, subacute, and neonatal lupus. It provides details on the clinical presentations, pathogenic mechanisms, and classification systems for the skin involvement in lupus.

![ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Enviromental factors

• SLE is a disorder in which the interplay between host factors (susceptibility

genes, hormonal) and environmental factors [ultraviolet (UV) radiation,

viruses, drugs] leads to loss of self-tolerance, and induction of

autoimmunity.

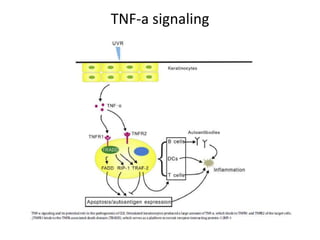

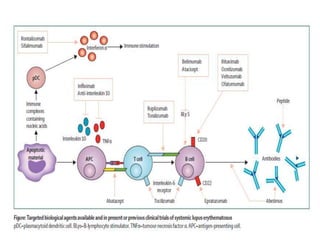

• Recent work has highlighted the important role of interferon-a signaling in

the pathogenesis of both SLE and LE specific skin disease.

• Drugs, viruses, UV light, and, possibly, tobacco, have been shown to

induce development of SLE.

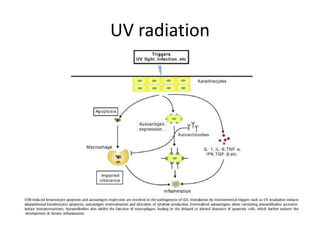

• UV radiation (UVR) is probably the most important environmental factor in

the induction phase of SLE and especially of LE-specific skin disease, UV

light likely leads to self-immunity and loss of tolerance because it causes

apoptosis of keratinocytes, which in turn, makes previously cryptic

peptides available for immunosurveillance , UVB radiation has been

shown to displace autoantigens such as Ro/SS-A and related autoantigens,

La/SS-B, and calreticulin, from their normal locations inside epidermal

keratinocytes to the cell surface.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lupus-200107231218/85/Lupus-Erythematosus-for-dermatologists-5-320.jpg)