This document describes the fabrication and testing of surface acoustic wave (SAW) devices. Five SAW devices were fabricated in a cleanroom using thin film deposition, photolithography, and wet etching processes. The devices were then tested as filters by measuring their bandwidth and operating frequencies using a network analyzer. Additionally, the potential for SAW devices to be used as biosensors was demonstrated by measuring frequency shifts when biotin solution was deposited on a quartz crystal microbalance, showing detection of added mass.

![1

Cleanroom Fabrication and Applications of Surface Acoustic

Wave Devices

Nitasha Goyal Madelyn Hutton Kevin Mao

nitashagoyal27@gmail.com maddyrhutton@yahoo.com kevinmao7@gmail.com

Walter Roper Soumya Sudhakar

wroper9910@gmail.com soumya96@gmail.com

Abstract

Beyond traditional uses as filters in radios and

cell phones, surface acoustic wave (SAW)

devices have applications in the medical field

as biosensors. Five SAW devices were

fabricated in the Rutgers MERL cleanroom

through the processes of thin film deposition,

photolithography, and wet etching.

Measurements of the bandwidths using 3

decibel (dB) width calculations and

measurements of operating frequencies of the

SAW devices showed functionality as filters.

Measurements of the mass of biotin

demonstrate the potential use of SAW devices

as microbalances and biosensors.

1 Introduction

Nanotechnology and microfabrication

have gained importance in today’s world since

the fields enable machines to be more energy

and cost efficient. One type of device in this

field is the surface acoustic wave (SAW)

device. Most commonly, SAW devices act as

frequency filters in instruments such as cell

phones and radios, selecting only a certain

bandwidth of frequencies. Today, research is

being conducted using SAW devices as

biosensors. Biosensors can be microbalances

that measure the mass of objects on a

microscale such as a strand of DNA. In

addition to aiding in genetic research such as

DNA hybridization, SAW devices can help

diabetic patients in blood glucose testing by

substantially reducing the amount of blood

collected. Some recent research is focused on

SAW devices’ ability to improve the efficiency

of solar panels[1]. In this work, SAW devices

were demonstrated successfully as filters and

used in the biosensing application as

microbalances.

2 Background

The microfabrication procedure has

been successfully improved in both research

and industry in the past decades. Our SAW

devices were fabricated in the cleanroom at

Rutgers’ Microelectronics Research

Laboratory (MERL).

2.1 The Cleanroom

A cleanroom is a lab in which certain

environmental pollutants are highly

controlled. This type of lab is commonly used

in fields that are sensitive to ecological

contamination such as semiconductor

manufacturing, biotechnology, and

microfabrication processes[2]. Despite its

name, cleanrooms are not sterile; rather, they

have a controlled level of airborne

contamination. Airflow rates and direction,

pressurization, temperature, humidity and

filtration are regulated to keep pollutants at a

minimum[3].

A cleanroom is necessary for the

fabrication process in order to preserve the

integrity of the devices made. Dust particles

in the air can interfere with the fabrication of

SAW devices during the fabrication process.

Since the SAW devices are on the microscale,

these dust particles are large enough to cause

the devices to be defective[4]. In addition to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2142ebb7-c0f8-4580-ae2c-0ae145f7d634-160521180355/75/Surface-Acoustic-Wave-Devices-1-2048.jpg)

![2

dust, other particulates in air, such as smoke,

bacteria, and cells, can also cause similar

problems in the devices. For these reasons,

microfabrication processes are carried out in

cleanrooms where the number of particulates

in the air can be controlled, decreasing the

probability of defective devices.

2.2 Surface Acoustic Wave Devices

SAW filters utilize interdigital

transducers (IDTs) and piezoelectricity to

produce surface acoustic waves.

IDTs consist of finger-like patterns

made of conductive material, such as

aluminum, as seen in Figure 2.1, and are used

to generate and receive the surface acoustic

waves. The number of fingers, the spacing

between the fingers, and the spacing between

the IDTs determines which frequencies are

able to travel through the circuit effectively.

Figure 2.1 Blue represents the IDTs of the SAW

device while yellow represents the quartz delay line.

Courtesy of Zheng Zhang, Rutgers University.

The SAW device utilizes the

piezoelectric effect by converting electrical

energy (AC voltage) to mechanical energy at

one end of the device and converting back to

electrical energy at the other end. The

piezoelectric effect refers to the electric

charge in response to pressure due to dipole

formation in the crystal lattice. The effect is

reversible; the inverse piezoelectric effect

results in the generation of mechanical strain

from an applied electric field. Voltage across

the input IDT generates a current which

energizes the quartz underneath the IDT

fingers. Quartz is a piezoelectric material. The

electrical energy is converted into mechanical

energy waves due to the contraction of the

quartz. The waves travel across the quartz to

the output IDT. The output IDT then

converts the mechanical waves back to

electrical energy, resulting in a voltage.

SAW-based processors are

lightweight and versatile and have low energy

consumption; therefore, they are

advantageous to use in portable wireless

communication devices[4].

2.3 Usage of SAW Devices as

Filters

One common use of SAW devices is

as filters found in appliances such as radios and

cell phones.

SAW devices filter frequencies

through the basic principles of wave

interference. When waves are in phase across

the device, they cause constructive

interference and are allowed through the

device. When waves are out of phase across

the device, they cause destructive interference

and are filtered[5]. The phase coherence

depends on the frequency of the waves (or the

wavelength), the distance between the IDTs

and the IDT periodicity.

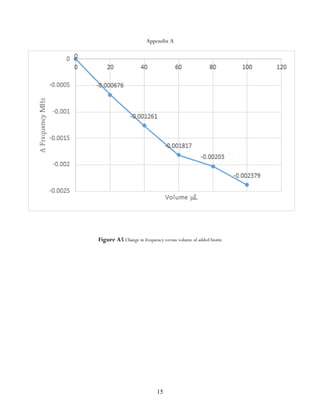

2.4 Quartz Crystal Microbalance

A new area of research involves using

acoustic wave devices as biosensors to

determine the mass of objects. In this work,

this application was demonstrated using the

quartz crystal microbalance (QCM). QCM is

also a piezoelectric device, but uses acoustic

waves propagating longitudinally rather than

tranversely. The biosensors in Figure 2.2

work since QCM devices can detect changes

in frequency. Using Equation 1, it is possible

to determine the change in mass.

Equation 1

= 3.336x103

m/s (acoustic velocity of quartz)

= 2.648x103

(density of quartz)

= 0.2047 cm3

(area of quartz)

= change in frequency

= fundamental frequency](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2142ebb7-c0f8-4580-ae2c-0ae145f7d634-160521180355/85/Surface-Acoustic-Wave-Devices-2-320.jpg)

![3

This microbalance can be used to

detect gas absorption as well as the

interactions between the biological molecules:

DNA-DNA, DNA-RNA, protein-protein, and

protein-small molecules.

Figure 2.2 Microbalance with the SAW device in

the center

Biotin is used in research to test the

microbalance since it is representative of

biomolecules that can be measured on a

microbalance[6].

Another device that can be used as a

biosensor is a quartz crystal microbalance

(QCM). QCMs have larger electrodes, thus

better suited for finding changes in

frequencies. Though not a SAW device,

QCMs also utilize piezoelectricity and are a

suitable replacement for measurement

purposes. The major difference between the

SAW device and the QCM is that the SAW

device operates on transverse waves whereas

the QCM operates on longitudinal waves.

2.5 Microfabrication Processes and

Measurement Principles

2.5.1 Mask

Masks are tools to imprint the design

of the device onto the photoresist on the

aluminum conductor. The mask has a chrome

pattern of the SAW device on a glass substrate

as seen in Figure 2.3. A mask with defects can

result in a low yield of chips[4].

Figure 2.3 Glass mask with chrome pattern

2.5.2 Photolithography and Wet

Etching

Photolithography includes the process

of spin coating photoresist on to the substrate.

This procedure has to be done in a yellow-lit

room since the photoresist reacts to UV light.

The layer of photoresist applied by spin

coating reacts with the concentrated UV light

during exposure[7].

The process used to expose the

photoresist to the light is contact printing.

Contact printing involves the wafer touching

the mask to allow for correct pattern transfer

during exposure. Contact printing may be

susceptible to dust particles on the wafer that

can potentially damage the mask; therefore,

proper care must be taken during the mask to

substrate contact[4].

The developing stage removes the

photoresist that has been exposed to UV light

during exposure, leaving the unexposed

photoresist to remain on the substrate. After

using this resist to pattern the aluminum by

wet etching, the photoresist is left on the

wafer to prevent corrosion; this process is

called passivation.

The etch rate of the aluminum is not

only dependent on the concentration of

solutes but also on the temperature of the

solution, the agitation of wafers, and the

impurities or alloys in the film[4].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2142ebb7-c0f8-4580-ae2c-0ae145f7d634-160521180355/85/Surface-Acoustic-Wave-Devices-3-320.jpg)

![4

2.5.3 Bandwidth and Operating

Frequency

The bandwidth is the optimal range of

frequencies that the device will allow. Any

frequency outside the bandwidth range will be

unlikely to resonate in the device. The

bandwidth is calculated by analyzing the

frequency values three decibels (dB) down

from the peak operating frequency – the

mode – and finding the width of the gap as

shown in Figure 2.4. The interval of 3 dB is

chosen since this marks the half power point -

the point at which the wave’s output power is

half that of its mid-band value.

The peak operating frequency is the

frequency associated with the wave that

experienced the most constructive

interference, as indicated by a high signal

strength. More than one operating frequency

can occur for each SAW filter. The resonance

of the waves results in a fundamental

frequency and additional harmonics, all of

which can be considered as multiple peak

operating frequencies.

Figure 2.4 The bandwidth of a wave between

frequency 1 and frequency 2

3 Microfabrication,

Measurements, and Biosensor

Application of SAW Devices

SAW devices and microbalances are

fabricated through a series of detailed steps

and tested.

3.1 Microfabrication of SAW

Devices in Cleanroom

Microfabrication includes electron

beam-physical vapor deposition,

photolithography, contact printing,

developing, and wet etching. This process was

done for five samples.

3.1.1 Cleaning and Electron Beam-

Physical Vapor Deposition

Cleaning of the quartz substrates was

done using acetone and methanol [8]. Next,

the wafer was rinsed with deionized water and

blown dry with nitrogen which quickly

evaporates any solvents or liquids on the

wafer. Nitrogen is used because it does not

cause the wafer to oxidize [9]. The wafer was

baked to dry and remove solvents. A film of

aluminum conductor was deposited on one

side of the quartz wafer by electron beam

physical vapor deposition [10], as shown in

Figure 3.1..

Figure 3.1 The samples of quartz substrate coated

with aluminum

3.1.2 Spin Coating

Spin coating began by placing the

sample in the middle of the spinner. A few

drops of photoresist (AZ 5124) were put onto

the center of the aluminum layer of the quartz

as seen in Figure 3.2 until the sample was

covered. To ensure the purity of the

photoresist, the tip of the dropper must not

touch the opening of the bottle nor the

sample. The substrate was then rotated at a

high speed in order to spread the coating](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2142ebb7-c0f8-4580-ae2c-0ae145f7d634-160521180355/85/Surface-Acoustic-Wave-Devices-4-320.jpg)

![5

evenly by centrifugal force. Rotation was

done for 5 seconds at 500 rpm and then

subsequently for 40 seconds at 4,000 rpm.

After the spinning was done, the wafer was

soft baked to dry off any solvent from the spin

coating, improve the adhesion of the resist to

the wafer, and anneal the stresses put on the

wafer during spin coating[11].

Figure 3.2 Spinner with the aluminum-coated

substrate (Sample 1) and pink photoresist (AZ 5124)

For Sample 2, an extra layer of

photoresist was applied due to a spinner

error. After applying the photoresist to

Sample 2, the spinner started immediately at

4,000 rpm, a higher speed than intended. As a

result, the spinning was stopped and Sample 2

was reexamined; some of the photoresist was

no longer on the chip. Photoresist was

reapplied to Sample 2 and the correct

program was used to spin Sample 2.

3.1.3 Mask and Exposure

The samples were positioned on the

stage in order to maximize the number of

chips on the samples. Once the shadow

disappeared as the sample contacted the mask,

the UV light was turned on; exposure lasted

for 15 seconds.

For all samples, the shadow was

examined in order to ensure the wafer was

just touching the mask. As the wafer moved

closer to the mask, the shadow diminished.

3.1.4 Image Developing

The sample was then soaked in a

developer to remove the exposed photoresist

leaving behind the pattern as seen in Figure

3.3. The developer was AZ 1:1 and was

compatible with the AZ 5214 photoresist.

The amount of time in the developer varies

depending on the sample, but is usually

around one minute. The samples were

dipped in distilled water, then removed, and

then dipped once again. This method was used

to ensure that all the developer was off the

wafer. The wafer was then dried using high-

pressure nitrogen.

Figure 3.3 Samples after developing

As seen in Table 1, the samples were

in the developing solution twice before the

photoresist was removed. They had to be

developed for 30 sec, dried, and developed

for 30 sec again to observe the development

progress. Sample 2 needed more time during

the developing stage. Sample 2 was developed

for 1 minute and 6 seconds, with two rounds

of 30 seconds each and a third round of 6

seconds. This was likely because at the earlier

spinning step, the photoresist was re-applied.

Sample Developing Time/Sequence Etching

Time

1 30 sec + rinse + 30 sec + rinse =

60 sec total

11:50

2 30 sec + rinse + 30 sec + rinse +

6 sec + rinse= 66 sec total

20:07

3 30 sec + rinse + 30 sec + rinse =

60 sec total

25:01

4 30 sec + rinse + 30 sec + rinse =

60 sec total

9:00

5 30 sec + rinse + 30 sec + rinse=

60 sec total

10:42

Table 1 Developing and etching times](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2142ebb7-c0f8-4580-ae2c-0ae145f7d634-160521180355/85/Surface-Acoustic-Wave-Devices-5-320.jpg)

![10

our gratitude to Robert Lorber for the

cleanroom technical support. We would also

like to thank The Governor’s School of

Engineering and its sponsors: Rutgers, The

State University of New Jersey, Morgan

Stanley, NJ Resources, South Jersey

Industries, PSE&G, and the GSET alumni and

community. Furthermore, we would like to

thank Jean Patrick Antoine, and all of the

counselors for giving us this opportunity. A

special thank you to Jeff Kowalski, our

Residential Teaching Associate, for always

being there for us and taking us to where we

need to be.

References

[1] "Highly Efficient Photovoltaic Energy

Conversion Using Surface Acoustic Waves in

Piezoelectric Semiconductors | University of

Maryland Energy Research Center." Highly

Efficient Photovoltaic Energy Conversion Using

Surface Acoustic Waves in Piezoelectric

Semiconductors | University of Maryland Energy

Research Center. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 July 2013.

<http://www.umerc.umd.edu/projects/sol

ar05>.

[2] “In NASA’s Sterile Areas, Plenty of

Robust Bacteria.” New York Times, 9.

October 2007.

[3] McFadden, Roger. "A Basic Introduction

to Clean Room." Coastwide Laboratories. N.p.,

n.d. Web. 5 July 2013.

<http://www.coastwidelabs.com/Technical

%20Articles/Cleaning%20the%20Cleanroom

.htm>.

[4] Ng, Kwok K. “Lithography and Etching.”

Semiconductor Device Technology. By Simon

M. Sze. N.p.: Wiley, 2005. 404-18. Print.

[5] Coon, Allan. "SAW Filter PCB Layout."

RFM. N.p., n.d. Web. 19 July

2013.

<http://www.rfm.com/products/apnotes/a

n42.pdf>.

[6] "What Is Biotin?" WiseGEEK. N.p., n.d.

Web. 19 July 2013.

<http://www.wisegeek.org/what-is-

biotin.htm>.

[7] "Photolithography." Photolithography.

N.p., n.d. Web. 05 July 2013.

<http://www.ece.gatech.edu/research/labs

/vc/theory/photolith.html>.

[8] "Cleaning Procedures for Class

Substrates." UCIRvine, n.d. Web. 5 July

2013.

<http://www.inrf.uci.edu/wordpress/wp-

content/uploads/sop-wet-cleaning-pro-for-

glass-substrates.pdf>.

[9] Downie, N. A. Industrial Gases. London:

Blackie Academic & Professional,

1997.Google Books. Web. 5 July 2013.

[10] "Electron Beam Physical Vapour

Deposition (EB-PVD)." Phoenix Scientific

Industries Ltd. N.p., n.d. Web. 04 July 2013.

<http://www.psiltd.co.uk/Products/Deposi

tionSystems/ElectronBeam/tabid/238/langu

age/en-GB/Default.aspx>.

[11] "Coating Quality and Spin

Coating." Materials Science and Engineering.

N.p., n.d. Web. 25 July 2013.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2142ebb7-c0f8-4580-ae2c-0ae145f7d634-160521180355/85/Surface-Acoustic-Wave-Devices-10-320.jpg)