This document discusses the entertainment economy and industry from an economic perspective. It defines entertainment and discusses how entertainment is influencing society and becoming a major economic force. Entertainment economics examines how entertainment organizations use resources to produce content and satisfy audience wants and needs. The document also outlines some key aspects of the entertainment industry like the different types of firms, industries, levels of competition, and forces that shape the industry such as globalization, regulation, technology and social aspects.

![EUROPEAN COURSE IN ENTREPRENEURSHIP FOR THE CREATIVE INDUSTRIES

9

Locally, globally, internationally, we

are living in a digital entertainment

economy

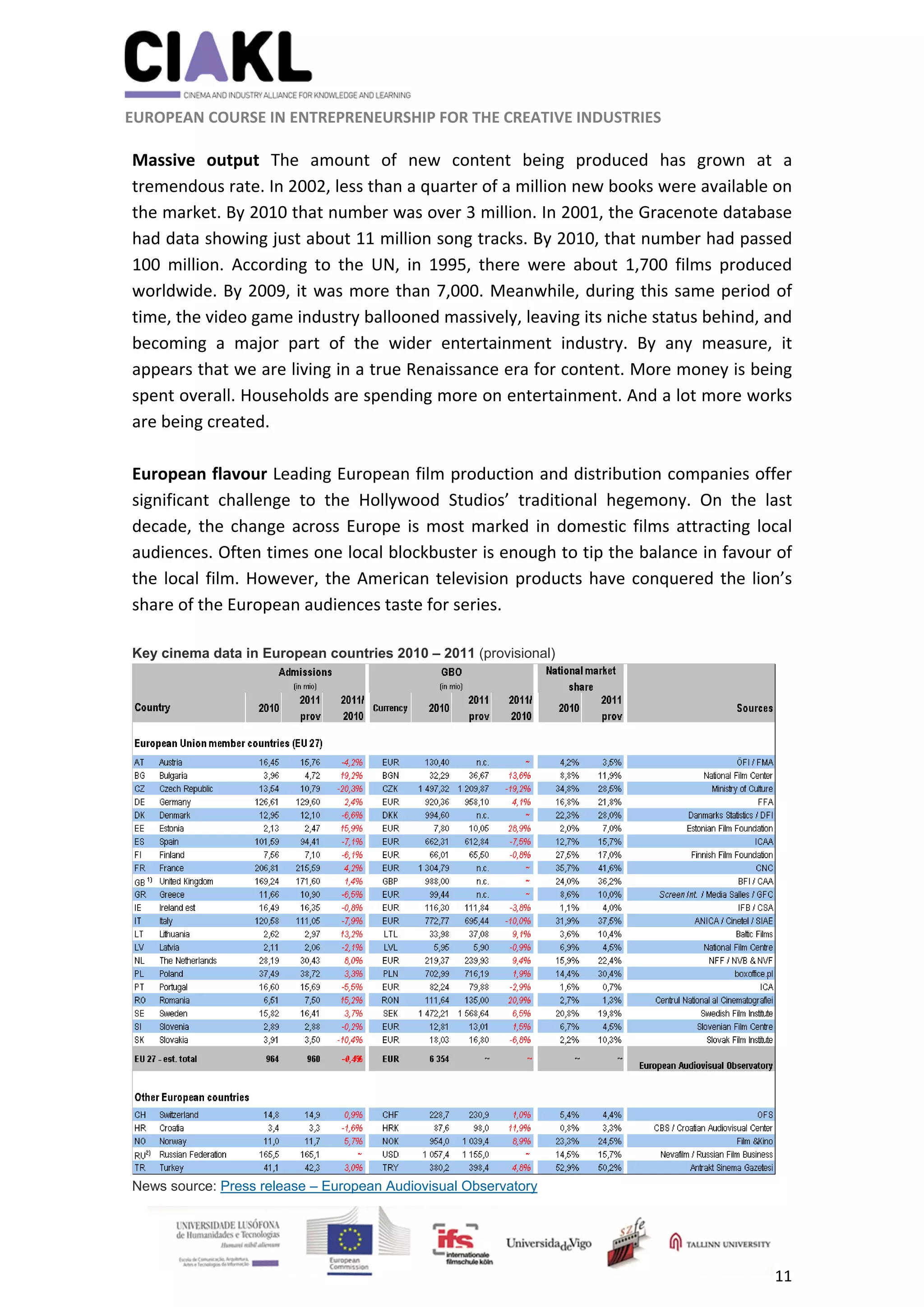

The Hollywood Studio System under challenge At the heart of the economic structure

of the film business lie the Hollywood Studios. These are the six major distributors,

based in Los Angeles but with worldwide exploitation systems that consistently hold

the greatest share of the world film market. However, only two of the Studios are

today wholly owned by American interests. This means that the business is truly

global. The Studios utilize the vertical economic approach by releasing the films

theatrically first, and ensuring increased revenues and profits through creating a

system of “windows” where the film is not released onto the next form of media until

the exploitation in its previous one has been exhausted. They also strategically apply

the horizontal approach acquiring rights to any possible territories in which a film

could be exploited. Increasingly, over the last decade the Studios have seen their

dominance over both conduits of exploitation under increasing pressure and, in certain

cases, market erosion. This model is being challenged by the Internet. New

technologies have shrunk and opened up the vertical chain model. Increasingly, films

are distributed at different stages of the old value chain, and move on from there. The

windows system is breaking up.

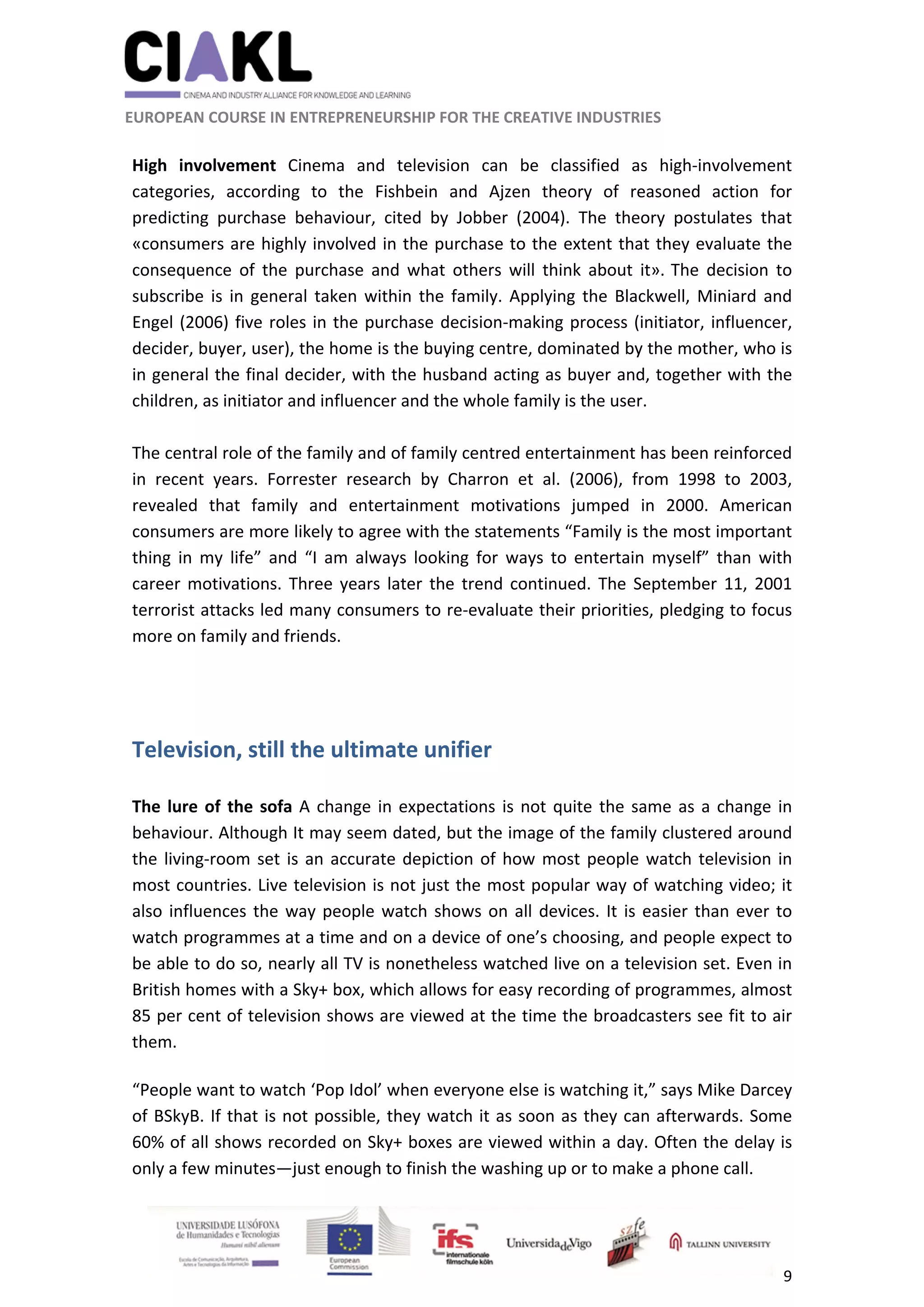

Sturm und CSI However, Europeans still love American television series, albeit not at

prime‐time. The value of imported drama series for European broadcasters was $5,990

million in 2011, with the top 200 titles supplying 81% ($4,829 million) of that total. The

Imported Drama Series in Europe report estimated that the top 10 titles accounted for

23 per cent ($1,400 million) of the 2011 total value, with the top 50 taking 55% ($3,268

million). CBS distributed the top three titles in 2011, with NCIS leading the pack by

generating $210 million. The three CSI franchises appear in the top 10. Only one of the

top 10 titles (Sturm der Liebe) originated from outside the US. Only 22% of the hours

screened for the top 200 titles appeared in primetime [20,507 hours from 94,638 in

total]. However, 69 per cent [$3,337 million] of the value created for these titles was in

primetime.

The top six US distributors dominate the top 200, creating nearly three‐quarters of the

value and 56 per cent of the titles. CBS is the clear leader, with second‐placed Warner

Bros some way behind. However, these six companies are probably not as dominant as](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/moduleelectiveciaklii-class02-160301160908/75/Subject-Module-Elective-CIAKL-II-Class-02-9-2048.jpg)

![EUROPEAN COURSE IN ENTREPRENEURSHIP FOR THE CREATIVE INDUSTRIES

10

many people would have guessed. Indeed, seventh‐placed ZDF [$183 million, 12 titles]

was pretty close to Sony in 2011. ITV was next with $116 million [9 titles]. Ninth place

(and the only other distributor to record more than $100 million from Europe’s top

200 titles) went to Bavaria Media [$113 million], but this was solely for Sturm der

Liebe.

The Internet renaissance The wider entertainment industry is growing at a rapid pace

(contrary to doom & gloom messages). Furthermore, more content creators are

producing more content than ever before ‐‐ and are more able to make money of their

content than ever before. On top of that, consumers are living in a time of absolute

abundance and choice ‐‐ a time where content is plentiful in mass quantities, leading

to a true renaissance for them. This does present a unique challenge for some

companies used to a very different market, but it’s a challenge filled with opportunity:

the overall market continues to grow, and smart businesses are snapping up pieces of

this larger market. The danger is in standing still or pretending the market is shrinking.

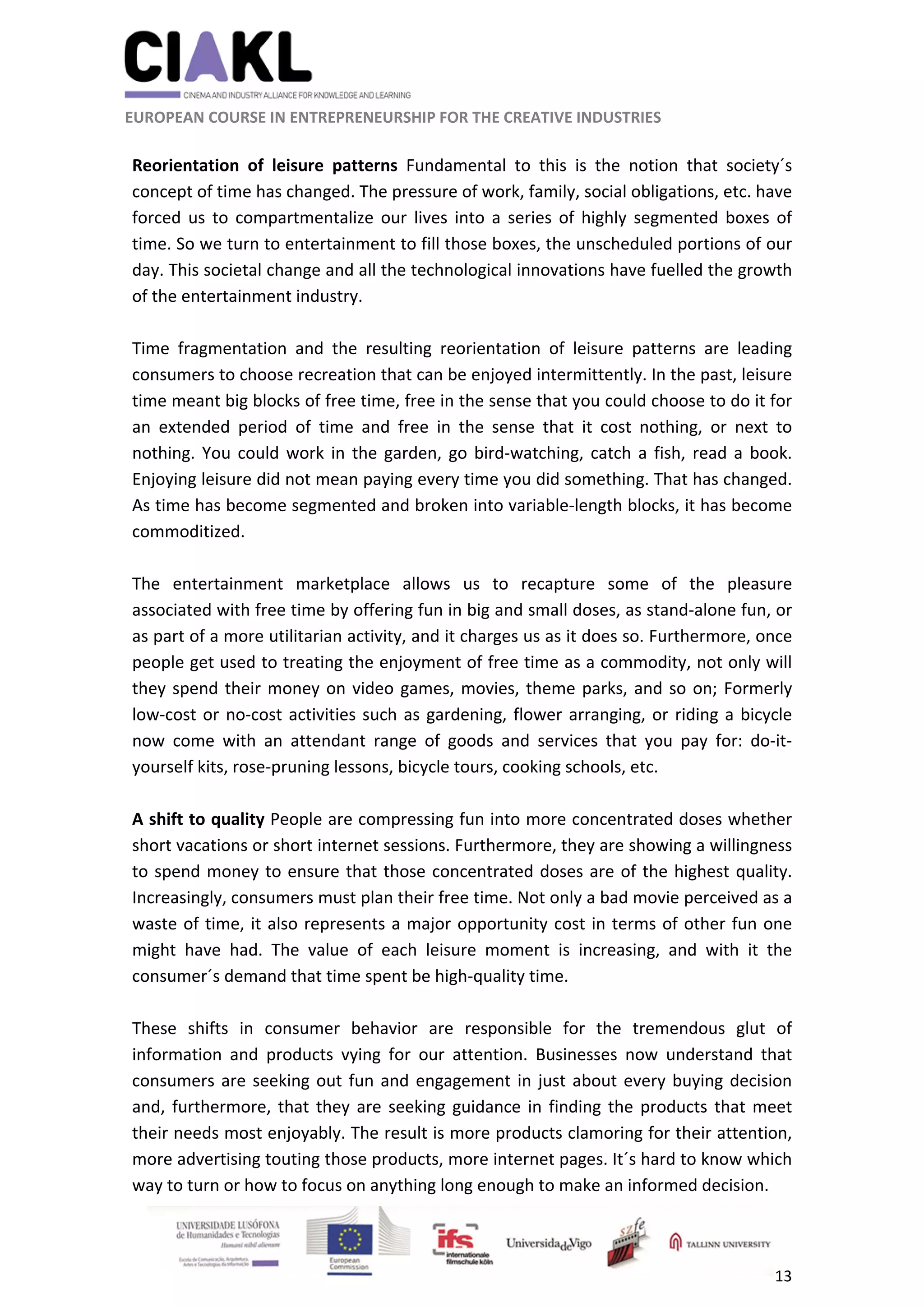

Don’t miss the opportunity Data from PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) and iDATE show

that from 1998 to 2010 the value of the worldwide entertainment industry grew from

$449 billion to $745 billion. That’s quite a leap for a market supposedly being

decimated by technological change. Of course, the world economy grew over this

period of time, but a particularly compelling bit of data shows that, in the US

specifically, consumer spending on entertainment as a percentage of income has

continued to rise significantly over the last decade. According to the Bureau of Labor

Statistics, in 2000, 4.9 per cent of total household spending went to entertainment.

That number gradually increased over the decade ‐‐ and by 2008, it was up to 5.62 per

cent, an increase of nearly 15 per cent in the same decade as the internet went

mainstream.

More independent jobs Similarly, reports of job losses in the sector are equally hard to

square with reality. Once again, looking at the Bureau of Labor Statistics data,

employment in the entertainment sector grew nicely in the decade from 1998 to 2008

‐‐ rising by nearly 20% over that decade. The BLS continues to predict similar growth

for the next decade as well. Perhaps even more importantly, during that same period

of time, BLS data shows that the number of people who were independent artists grew

at an even faster rate – over 43 per cent growth in that same decade. In fact, this may

be a strong hint as to why you hear reports of industry "demise" from certain legacy

players: because new technologies and services have made it much easier for content

creators to find success without going through the traditional gatekeepers.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/moduleelectiveciaklii-class02-160301160908/75/Subject-Module-Elective-CIAKL-II-Class-02-10-2048.jpg)