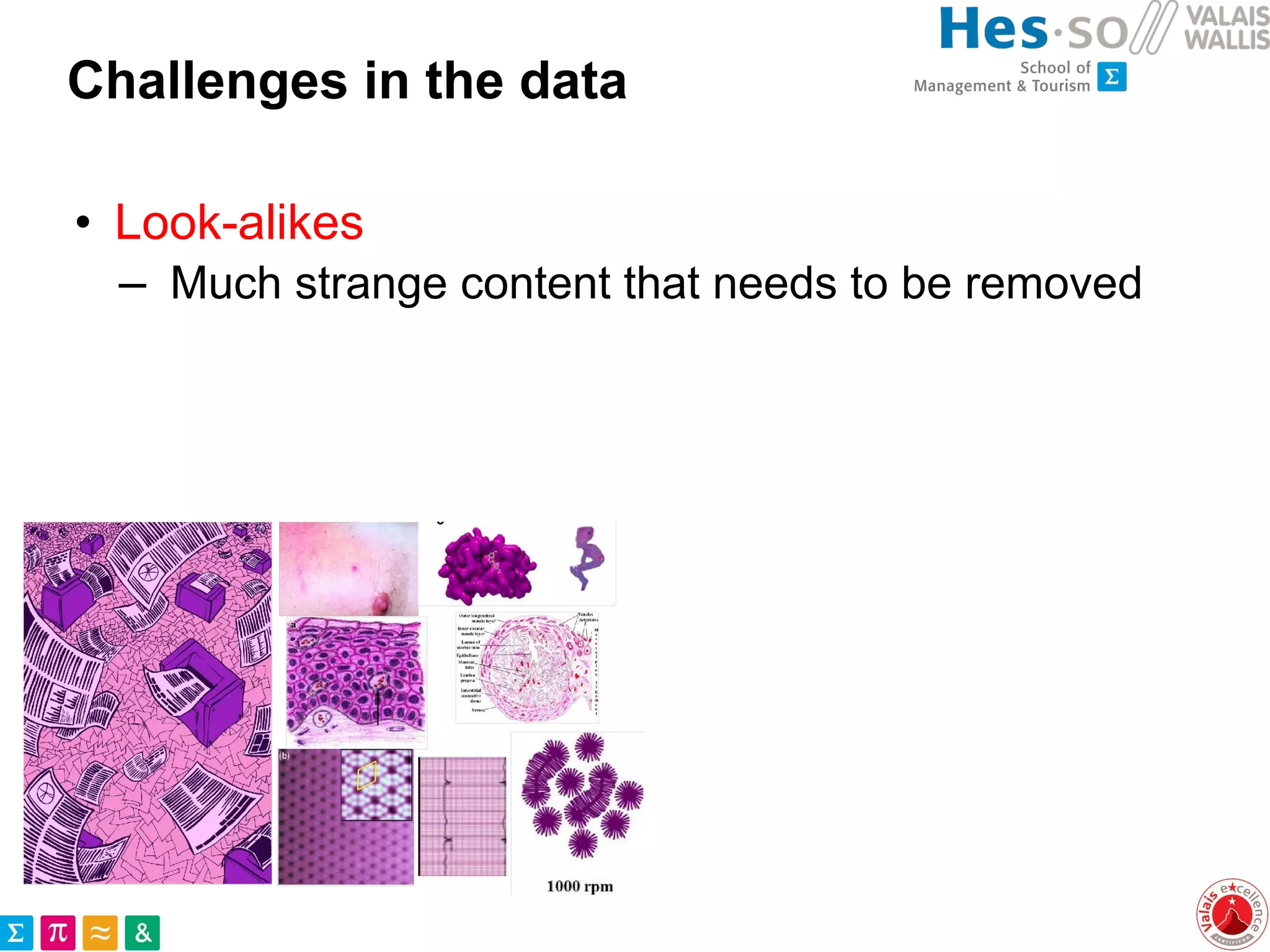

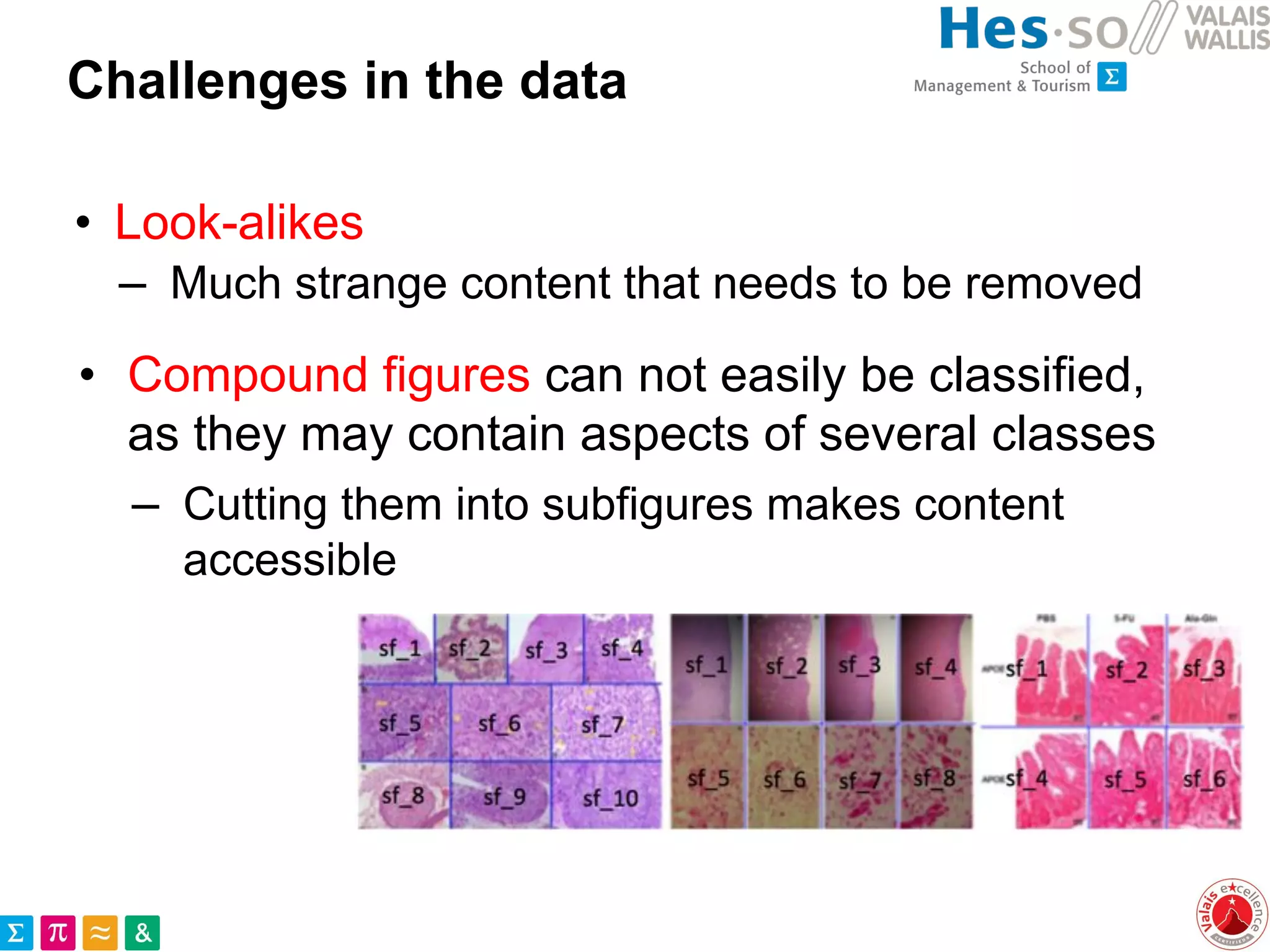

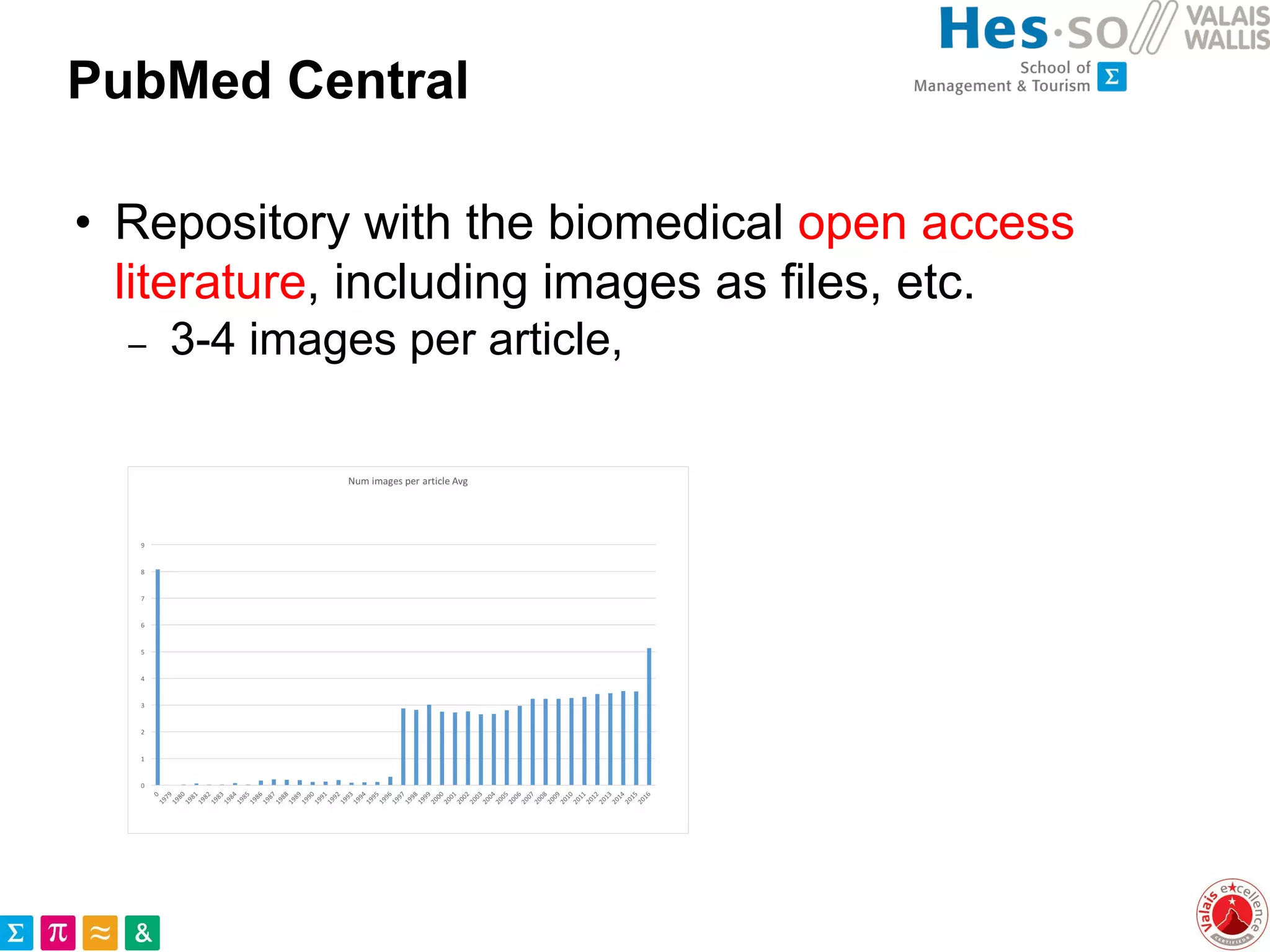

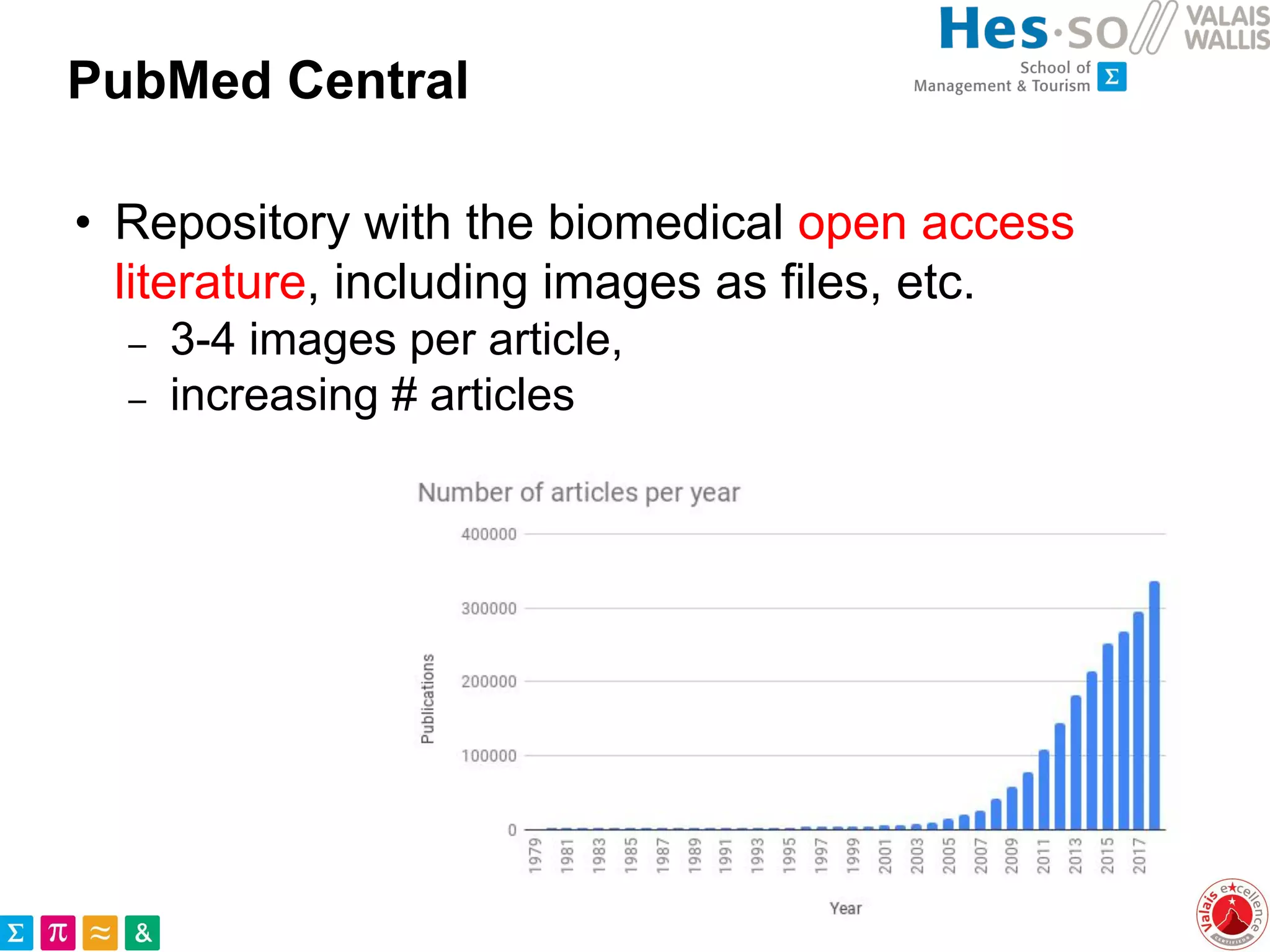

This document discusses the utilization of public medical images from open access literature and social networks for enhancing deep learning model training in image analysis. It highlights the challenges of data diversity, class imbalances in rare diseases, and the need for effective data aggregation and filtering techniques. The article also emphasizes the advantages of using diverse and rare images from various sources alongside next steps for improving data curation and machine learning tasks.

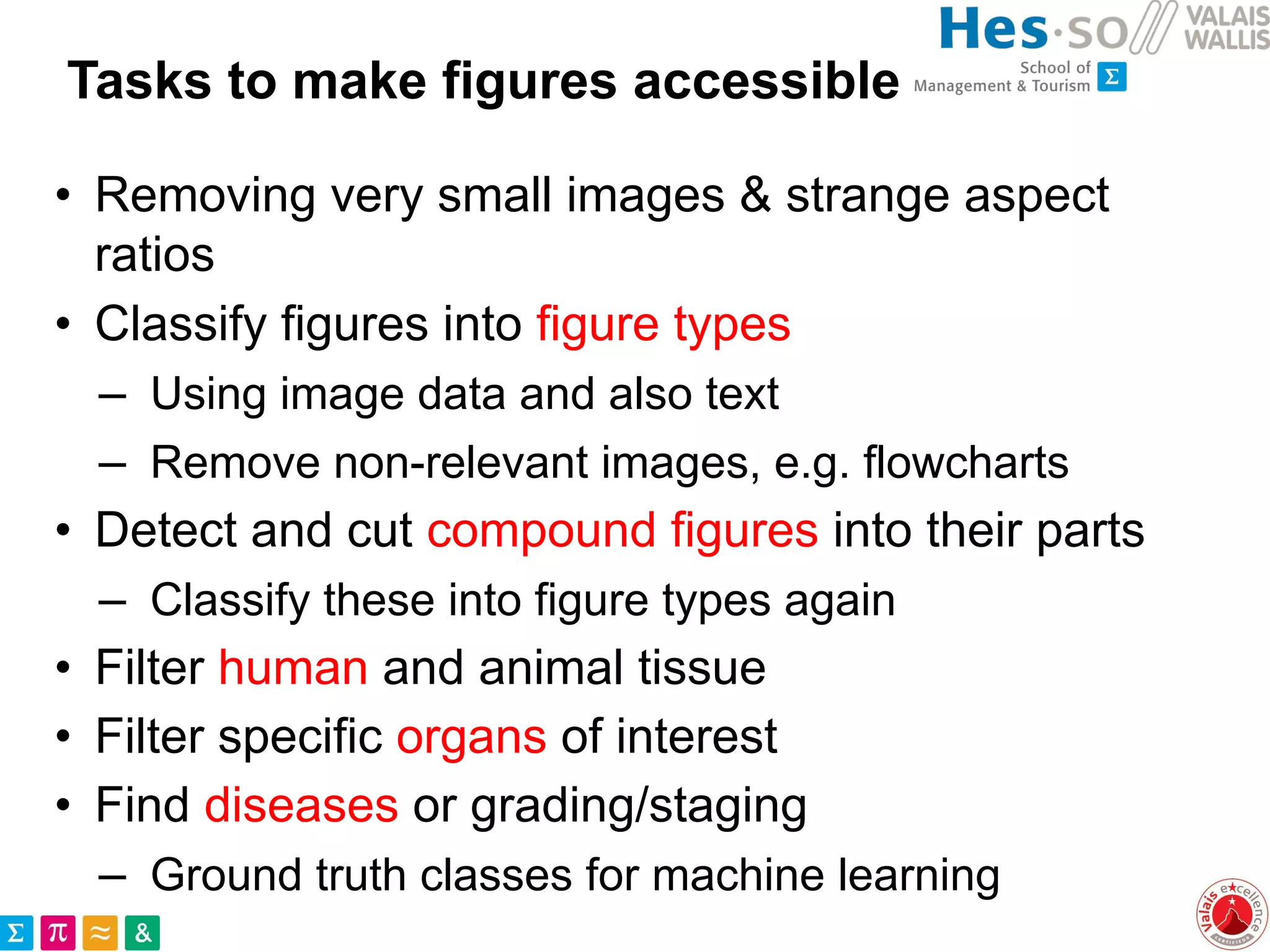

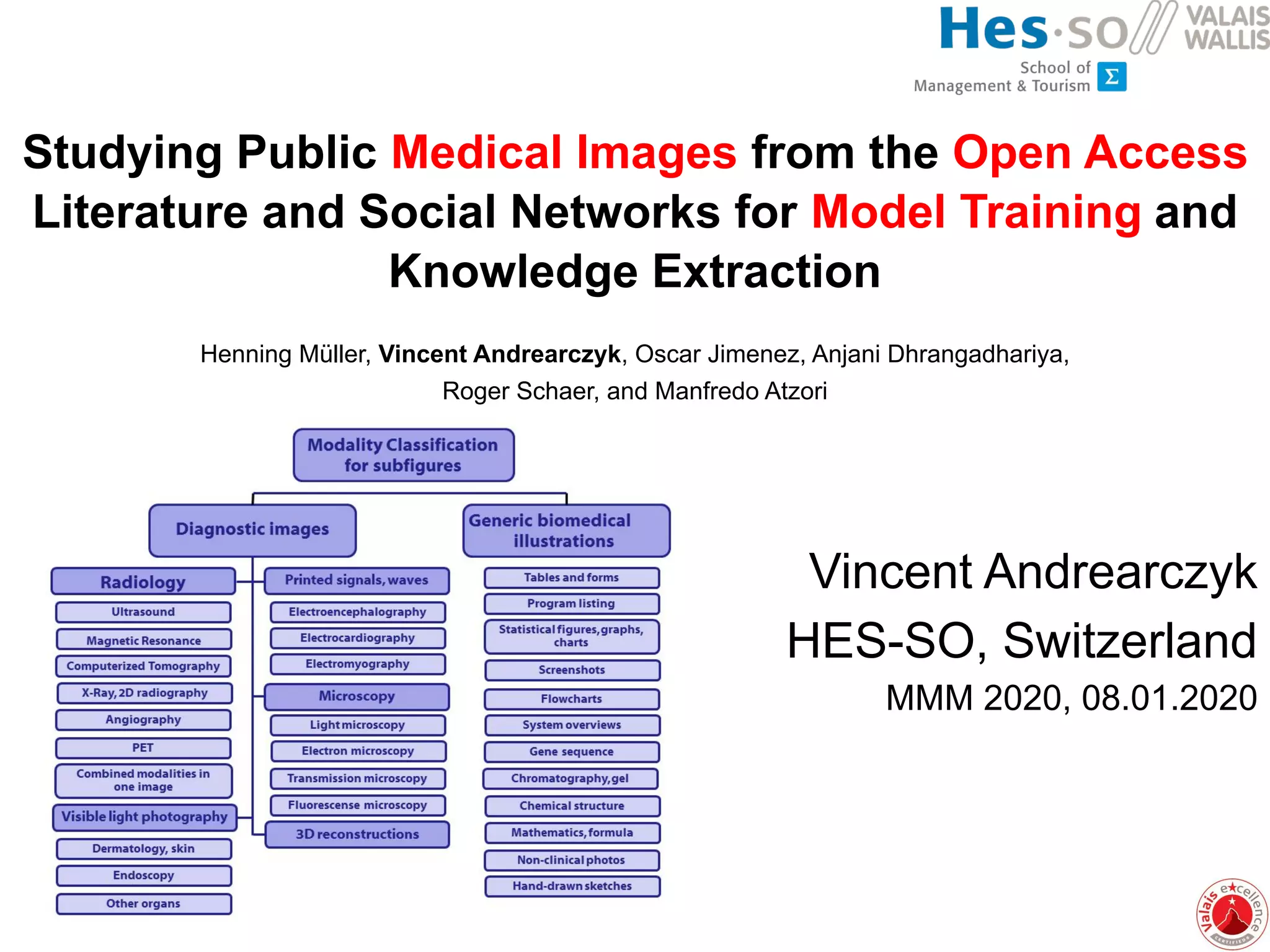

![Structuring the visual content

• Define types of images to make the literature

images classifiable

– Extremely large variety in most categories

– Many sub-categories are possible

– Categories with clinical relevance

are most important

– Allows removing noise

– Compound figures

are separately treated

[ImageCLEF 2013]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pdfpresentationmmm2020-200131151239/75/Studying-Public-Medical-Images-from-Open-Access-Literature-and-Social-Networks-for-Model-Training-and-Knowledge-Extraction-8-2048.jpg)