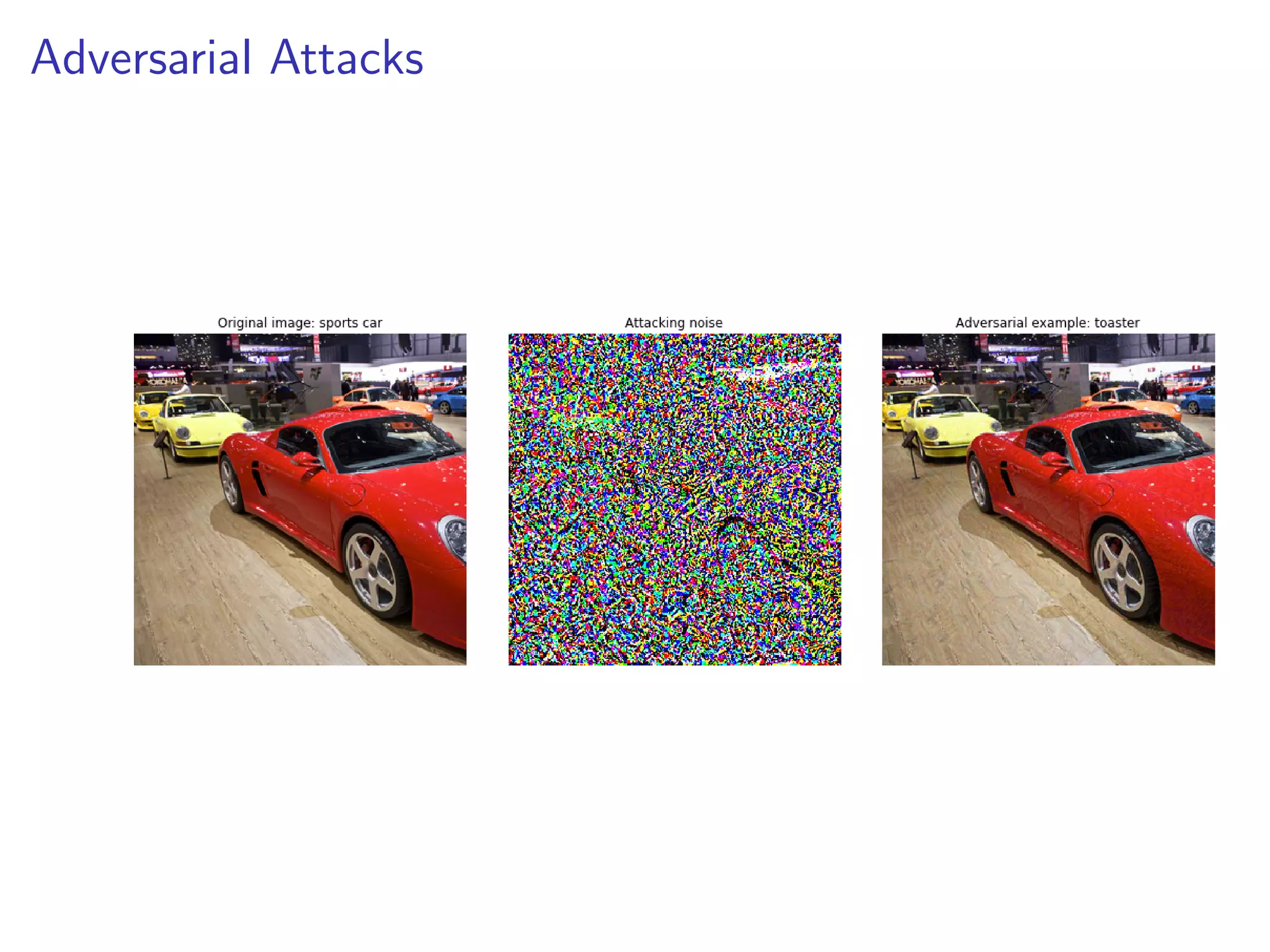

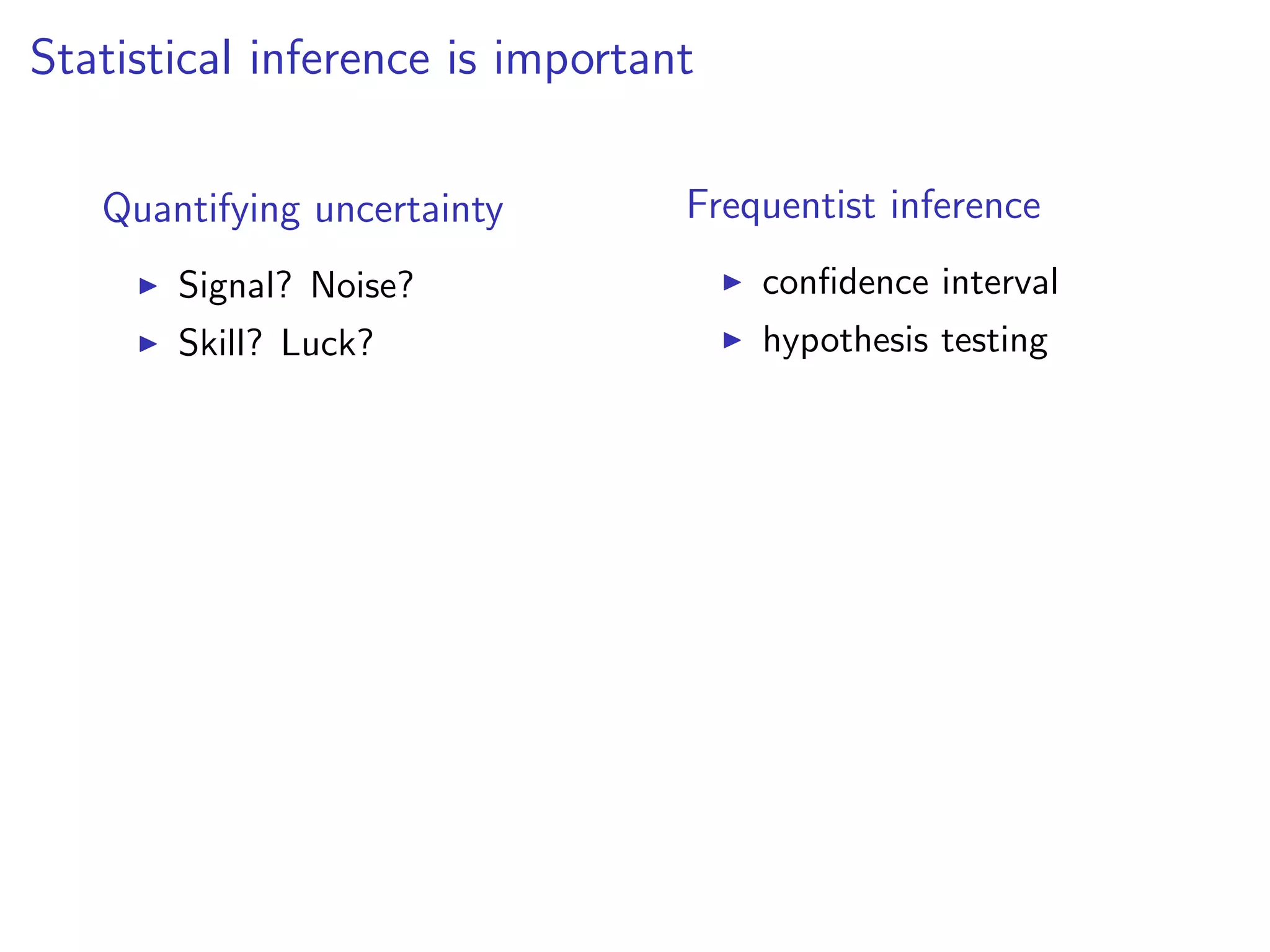

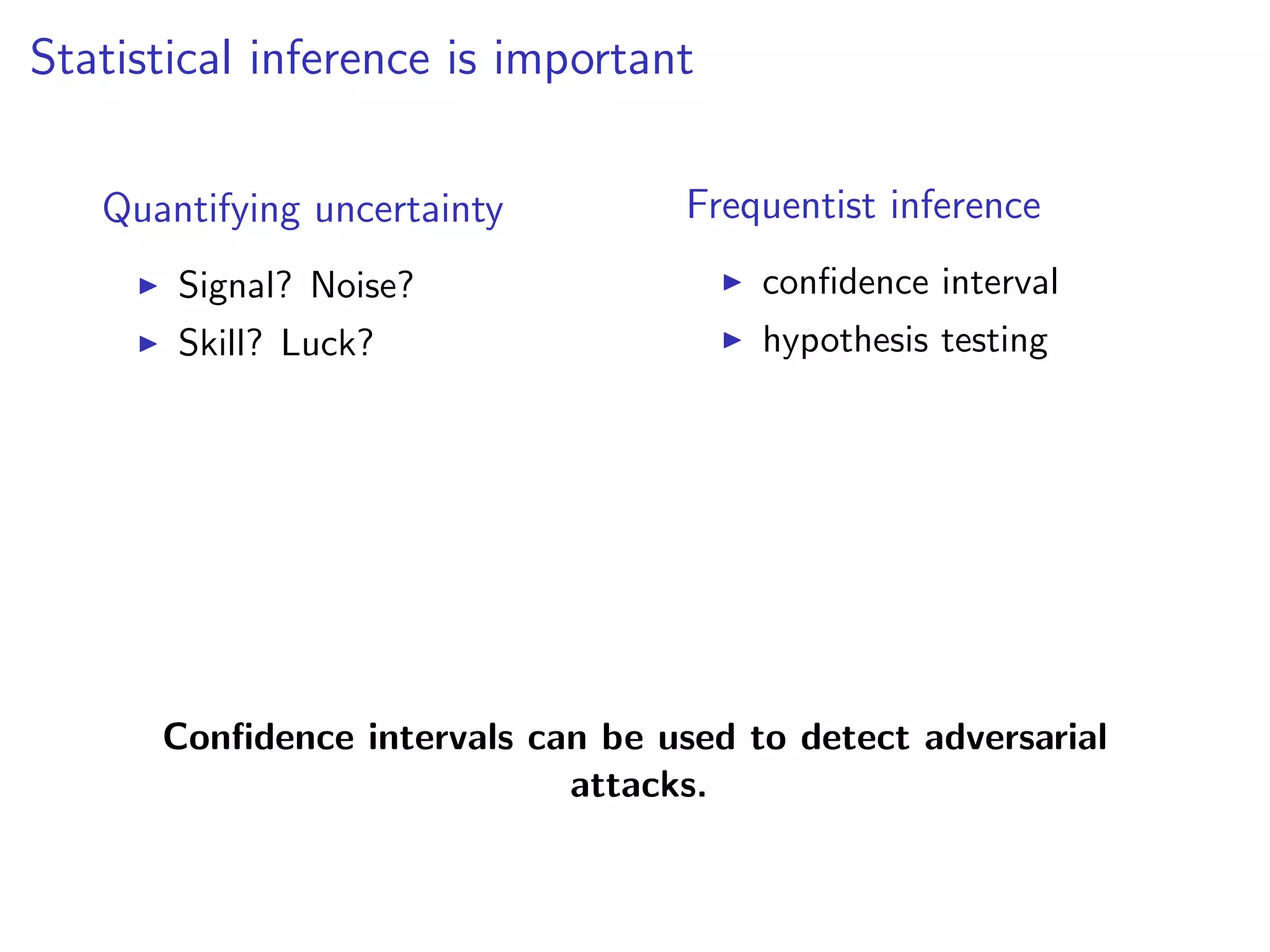

This document discusses the application of stochastic gradient descent (SGD) for statistical inference, particularly in the context of detecting adversarial attacks in machine learning. It outlines how confidence intervals can be computed using SGD, which is more efficient than traditional bootstrap methods for large data problems. The work emphasizes the practical advantages of using SGD for both inference and optimization in statistical analysis.

![SGD in ERM – mini batch SGD

To solve empirical risk minimization (ERM)

f (θ) =

1

n

n

i=1

fi (θ),

where fi (θ) = θ(Zi ).

At each step:

Draw S i.i.d. uniformly random indices It from [n] (with

replacement)

Compute stochastic gradient gs(θt) = 1

S i∈It

fi (θt)

θt+1 = θt − ηgs(θt)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/44constantine-dstop-2018-181128221033/75/Statistical-Inference-Using-Stochastic-Gradient-Descent-5-2048.jpg)

![Asymptotic normality – classical results

M-estimator – statistics

When number of samples n → ∞,

√

n(θ − θ∗

) N(0, H∗−1

G∗

H∗−1

),

where G∗ = EZ [ θ θ∗ (Z) θ θ∗ (Z) ] and H∗ = EZ [ 2

θ θ∗ (Z)].

Stochastic approximation – optimization

When number of steps t → ∞,

√

t

1

t

t

i=1

θt − θ N(0, H−1

GH−1

),

where G = E[gs(θ)gs(θ) |= θ] and H = 2f (θ).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/44constantine-dstop-2018-181128221033/75/Statistical-Inference-Using-Stochastic-Gradient-Descent-6-2048.jpg)

![Asymptotic normality – classical results

M-estimator – statistics

When number of samples n → ∞,

√

n(θ − θ∗

) N(0, H∗−1

G∗

H∗−1

),

where G∗ = EZ [ θ θ∗ (Z) θ θ∗ (Z) ] and H∗ = EZ [ 2

θ θ∗ (Z)].

Stochastic approximation – optimization

When number of steps t → ∞,

√

t

1

t

t

i=1

θt − θ N(0, H−1

GH−1

),

where G = E[gs(θ)gs(θ) |= θ] and H = 2f (θ).

SGD not only useful for optimization,

but also useful for statistical inference!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/44constantine-dstop-2018-181128221033/75/Statistical-Inference-Using-Stochastic-Gradient-Descent-7-2048.jpg)

![Statistical inference using mini batch SGD

burn in

θ−b, θ−b+1, · · · θ−1, θ0,

¯θ

(i)

t =1

t

t

j=1 θ

(i)

j

θ

(1)

1 , θ

(1)

2 , · · · , θ

(1)

t

discarded

θ

(1)

t+1, θ

(1)

t+2, · · · , θ

(1)

t+d

θ

(2)

1 , θ

(2)

2 , · · · , θ

(2)

t θ

(2)

t+1, θ

(2)

t+2, · · · , θ

(2)

t+d

...

θ

(R)

1 , θ

(R)

2 , · · · , θ

(R)

t θ

(R)

t+1, θ

(R)

t+2, · · · , θ

(R)

t+d

At each step:

Draw S i.i.d. uniformly random

indices It from [n] (with replacement)

Compute stochastic gradient

gs(θt) = 1

S i∈It

fi (θt)

θt+1 = θt − ηgs(θt)

Use an ensemble of i = 1, 2, . . . , R estima-

tors for statistical inference:

θ(i)

= θ +

√

S

√

t

√

n

(¯θ

(i)

t − θ).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/44constantine-dstop-2018-181128221033/75/Statistical-Inference-Using-Stochastic-Gradient-Descent-8-2048.jpg)

![Theoretical guarantee

Theorem

For a differentiable convex function f (θ) = 1

n

n

i=1 fi (θ), with gradient f (θ), let θ ∈ Rp be

its minimizer, and denote its Hessian at θ by H := 2f (θ) . Assume that ∀θ ∈ Rp, f satisfies:

(F1) Weak strong convexity: (θ − θ) f (θ) ≥ α θ − θ 2

2, for constant α > 0,

(F2) Lipschitz gradient continuity: f (θ) 2 ≤ L θ − θ 2, for constant L > 0,

(F3) Bounded Taylor remainder: f (θ) − H(θ − θ) 2 ≤ E θ − θ 2

2, for constant E > 0,

(F4) Bounded Hessian spectrum at θ: 0 < λL ≤ λi (H) ≤ λU < ∞, ∀i.

Furthermore, let gs(θ) be a stochastic gradient of f , satisfying:

(G1) E [gs(θ) | θ] = f (θ),

(G2) E gs(θ) 2

2 | θ ≤ A θ − θ 2

2 + B,

(G3) E gs(θ) 4

2 | θ ≤ C θ − θ 4

2 + D,

(G4) E gs(θ)gs(θ) | θ − G 2

≤ A1 θ − θ 2 + A2 θ − θ 2

2 + A3 θ − θ 3

2 + A4 θ − θ 4

2,

for positive, data dependent constants A, B, C, D, Ai , for i = 1, . . . , 4. Assume that

θ1 − θ 2

2 = O(η); then for sufficiently small step size η > 0, the average SGD sequence

θt = 1

t

n

i=1 θi satisfies:

tE[(¯θt − θ)(¯θt − θ) ] − H−1

GH−1

2

√

η + 1

tη + tη2,

where G = E[gs(θ)gs(θ) | θ].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/44constantine-dstop-2018-181128221033/75/Statistical-Inference-Using-Stochastic-Gradient-Descent-13-2048.jpg)

![Theoretical guarantee

Theorem

For a differentiable convex function f (θ) = 1

n

n

i=1 fi (θ), with gradient f (θ), let θ ∈ Rp be

its minimizer, and denote its Hessian at θ by H := 2f (θ) . Assume that ∀θ ∈ Rp, f satisfies:

(F1) Weak strong convexity: (θ − θ) f (θ) ≥ α θ − θ 2

2, for constant α > 0,

(F2) Lipschitz gradient continuity: f (θ) 2 ≤ L θ − θ 2, for constant L > 0,

(F3) Bounded Taylor remainder: f (θ) − H(θ − θ) 2 ≤ E θ − θ 2

2, for constant E > 0,

(F4) Bounded Hessian spectrum at θ: 0 < λL ≤ λi (H) ≤ λU < ∞, ∀i.

Furthermore, let gs(θ) be a stochastic gradient of f , satisfying:

(G1) E [gs(θ) | θ] = f (θ),

(G2) E gs(θ) 2

2 | θ ≤ A θ − θ 2

2 + B,

(G3) E gs(θ) 4

2 | θ ≤ C θ − θ 4

2 + D,

(G4) E gs(θ)gs(θ) | θ − G 2

≤ A1 θ − θ 2 + A2 θ − θ 2

2 + A3 θ − θ 3

2 + A4 θ − θ 4

2,

for positive, data dependent constants A, B, C, D, Ai , for i = 1, . . . , 4. Assume that

θ1 − θ 2

2 = O(η); then for sufficiently small step size η > 0, the average SGD sequence

θt = 1

t

n

i=1 θi satisfies:

tE[(¯θt − θ)(¯θt − θ) ] − H−1

GH−1

2

√

η + 1

tη + tη2,

where G = E[gs(θ)gs(θ) | θ].

Proof idea: H−1 = η i≥0(I − ηH)i](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/44constantine-dstop-2018-181128221033/75/Statistical-Inference-Using-Stochastic-Gradient-Descent-14-2048.jpg)