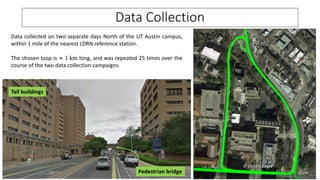

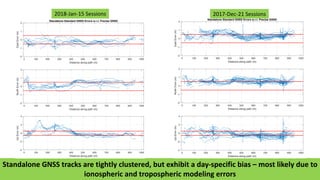

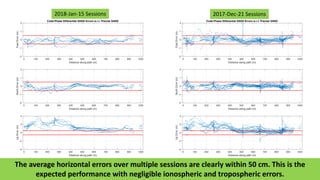

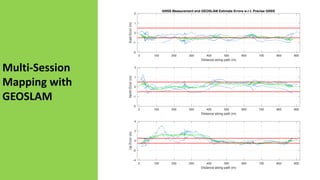

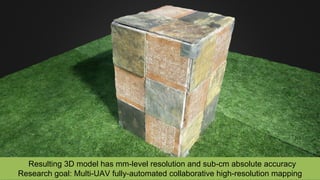

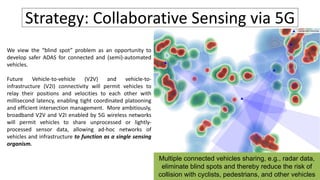

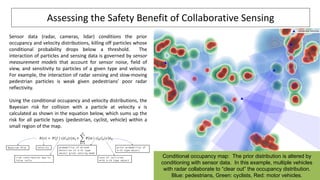

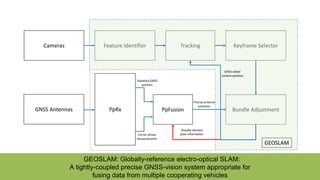

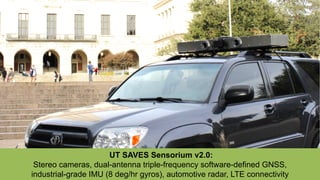

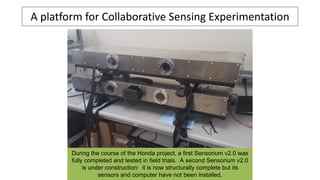

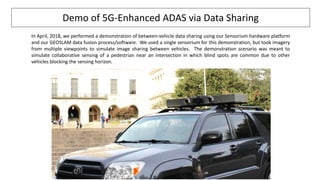

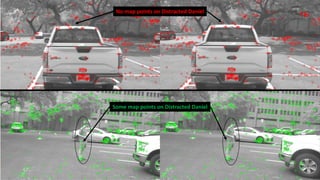

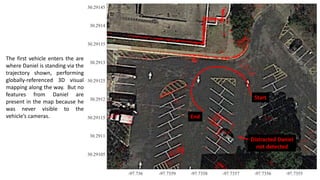

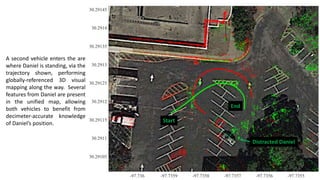

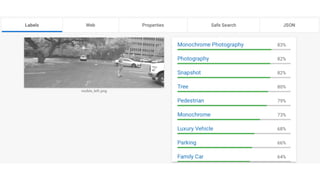

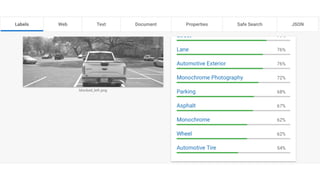

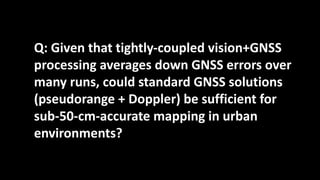

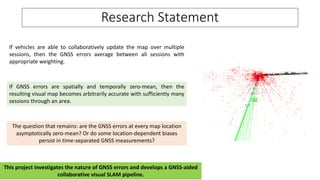

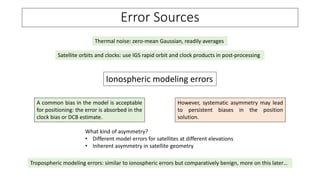

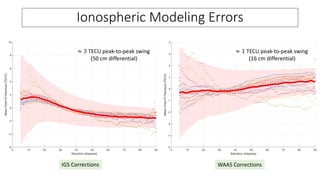

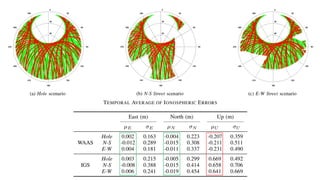

The document discusses the development of collaborative sensing systems for automated vehicles to address blind spots using 5G technology, enhancing safety in automated driving. It highlights the potential of vehicle-to-vehicle and vehicle-to-infrastructure connectivity to share sensor data, improving situational awareness and reducing collision risks. The document also details experimental setups and findings related to collaborative mapping and GNSS error assessments, ultimately aiming for high-resolution mapping capabilities in urban environments.

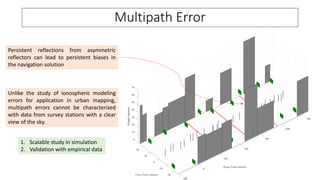

![Based on Land Mobile Satellite Channel

Model [1].

LOS: interaction with buildings, trees, poles

NLOS echoes: stochastic

Geometric echoes: reflective, persistent

1. Simulate multipath echoes

2. Scalar tracking with narrow correlator

3. Navigation filter (EKF)

Naïve receiver: persistent biases after 100

sessions

Ideal NLOS rejection: accept signals with at

least 10 dB LOS advantage

Realistic receiver with normalized

innovation test based NLOS exclusion](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06humphreysapril18-180626034311/85/Collaborative-Sensing-for-Automated-Vehicles-24-320.jpg)