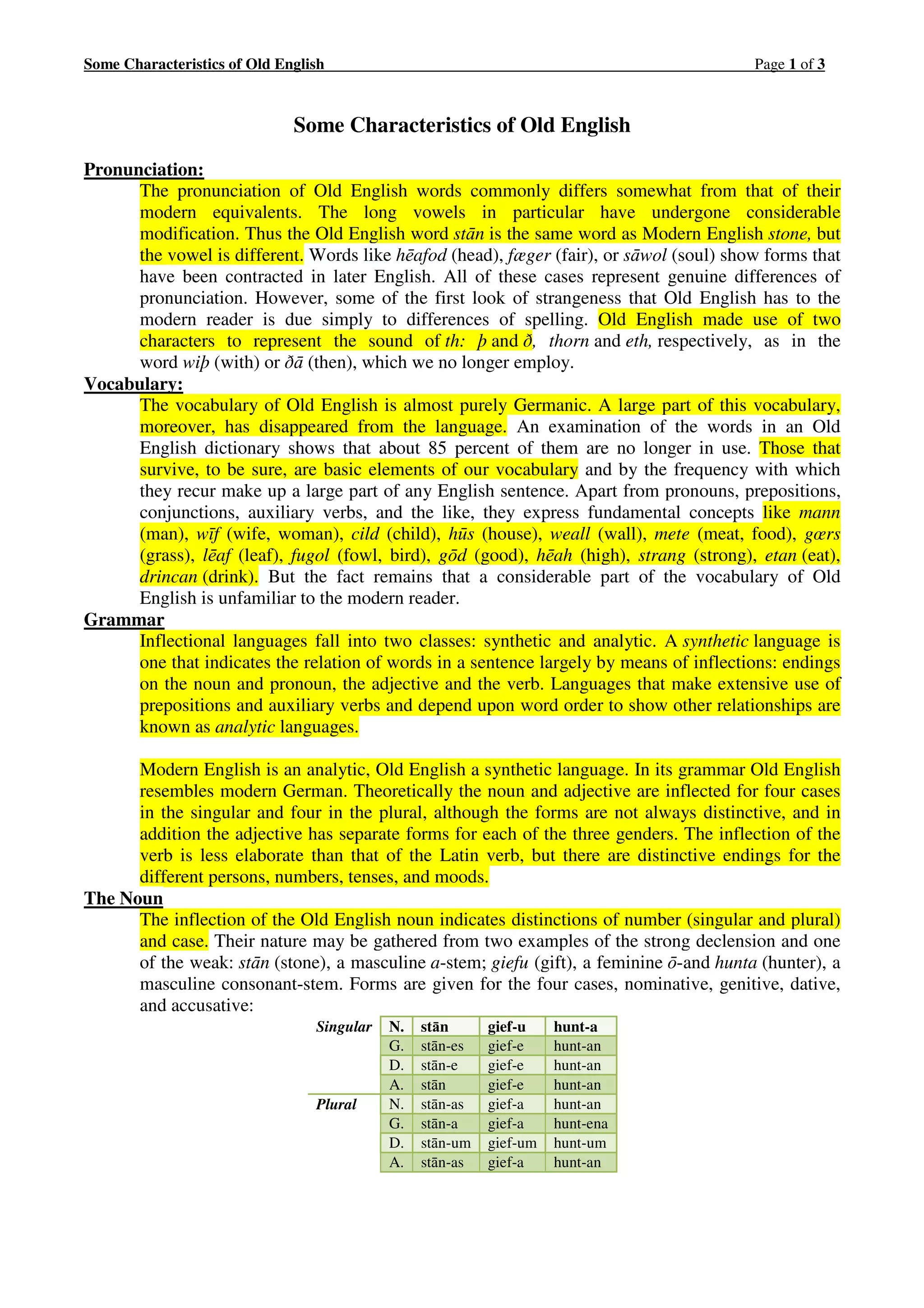

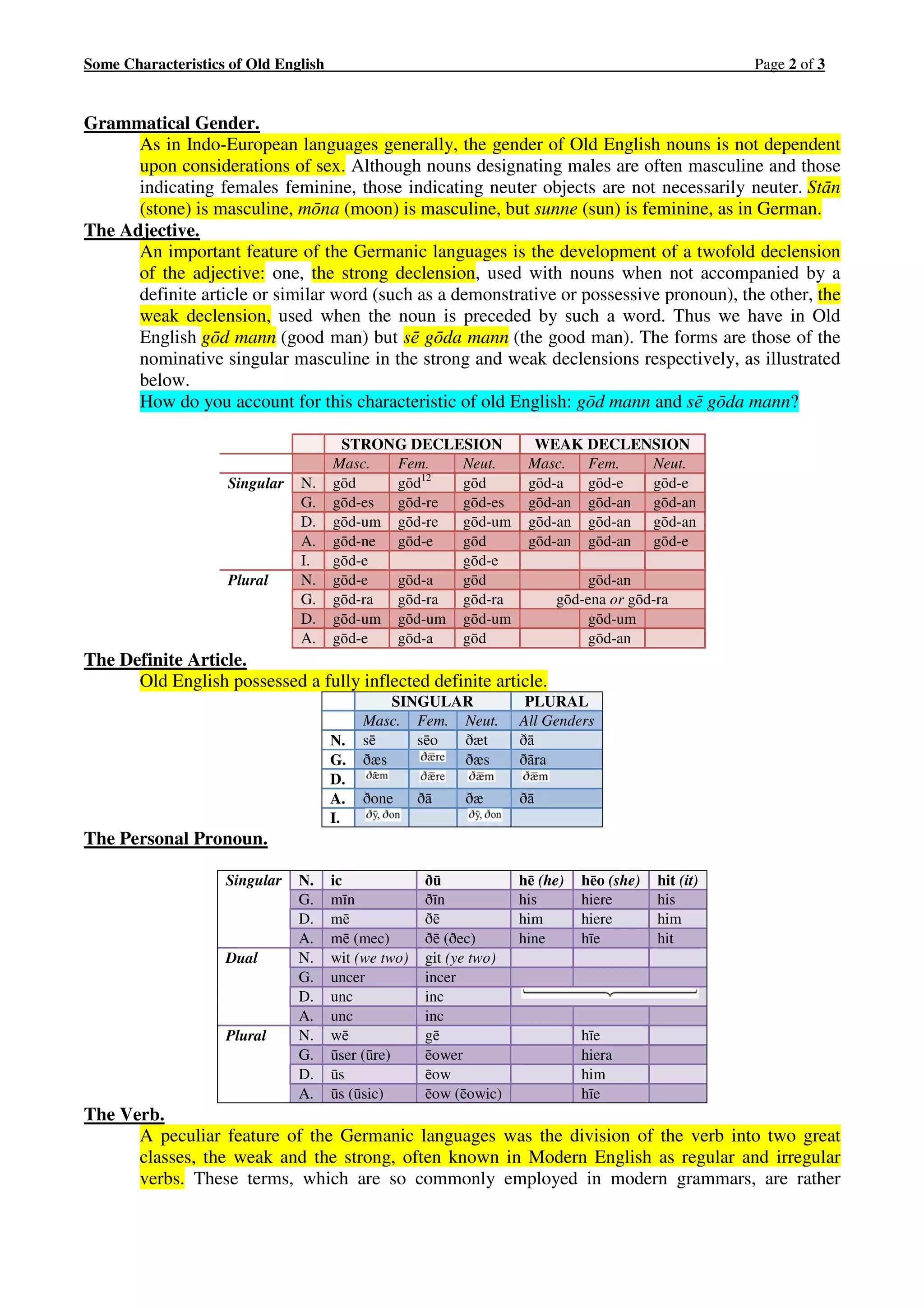

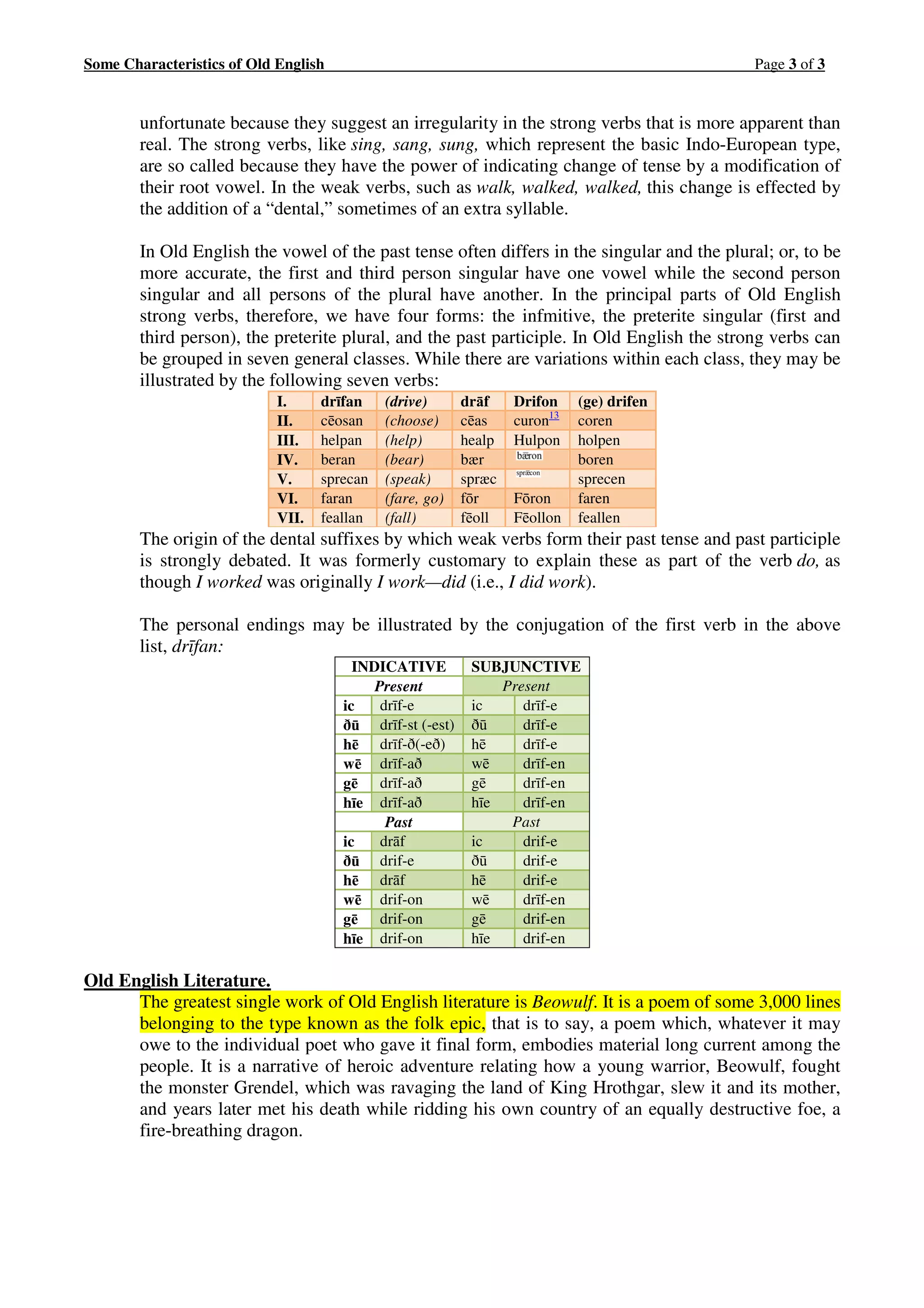

The document summarizes some key characteristics of Old English, including its pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar. Old English had a largely Germanic vocabulary and was a synthetic language with extensive inflectional endings. Nouns, adjectives, pronouns, and verbs all declined based on case, number, gender, and other grammatical features. The document provides examples to illustrate Old English inflectional patterns. It also briefly mentions the most famous work of Old English literature, the epic poem Beowulf.